Standard Chartered’s unexpected management reshuffle has raised some tricky questions about how, or whether, to communicate a company’s succession plans.

Although incumbent CEO Peter Sands said that he was ”not going anywhere,” a complete overhaul of the executives around him suggested otherwise. Two executives stepped down, including the person thought to be in line to take over as CEO, while another was promoted to deputy CEO, a new position that presumably marks the holder as the heir apparent. The bank’s share price tumbled to an 18-month low as investors puzzled at the mixed messages the moves sent about the bank’s succession policies.

The average tenure of CEO at a listed company in the US and Europe is around five years, so succession planning should never be far from the minds of boards of directors. But many still get it wrong, says Didier Cossin, a professor at Swiss business school IMD. Here are some of the ways directors can avoid succumbing to the haste, ambiguity and anxiety that strikes all too often when boards look for their company’s next boss.

Don’t rush, and don’t outsource the decision

Cowed by domineering CEOs who bristle at perceived challenges to their authority, some boards simply shirk responsibility for identifying and grooming potential successors until they are forced to decide. This often leads to directors outsourcing succession decisions to recruitment firms, which tend to favor outside candidates who are not as effective as home-grown talent.

Alternatively, boards can settle too quickly on a preferred CEO successor, which can undermine the incumbent CEO’s authority and alienate other managers who think they should be in the running. ”I’ve seen a large organization name a deputy CEO named and then, little by little, one of the other executive team members proved to be a better candidate,” Cossin recalls. “But he left the company because he knew he wouldn’t become CEO.”

A company should maintain a well-stocked and continuously refreshed roster of candidates and plan several years ahead, says Cossin. Directors should mentor the chosen few to prepare for the tasks they will face if they get the top job.

Tell the candidates, and no one else

Even when a board has decided on succession candidates, there are thorny questions about how to communicate this internally and externally. “Don’t assume people know that they’re in the running,” says Jill Ader, a consultant at recruitment firm Egon Zehnder in London.

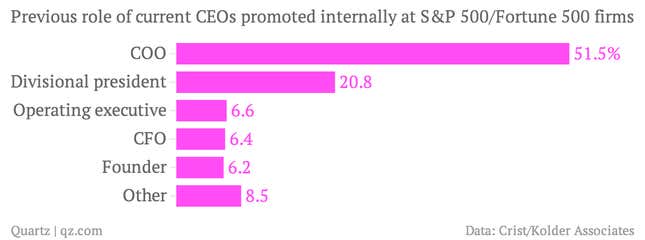

But beyond the CEO, board and the candidates themselves, the roster of potential successors shouldn’t be shared with the rest of the company, much less the outside world. Let journalists speculate about a company’s shortlist. “Make sure that the process isn’t vague, but the communication should be,” Ader notes. “Make it clear that you are grooming somebody without declaring your hand.” A handful of positions tend to feed into the CEO role, so it usually isn’t hard to guess who the internal candidates are to succeed the CEO. (Hint: It’s probably the COO.)

Letting slip who is in line to succeed the CEO risks creating “crown princes,” according to a CEO interviewed by Egon Zehnder for a recent report on succession best practices. This is how he explains his company’s approach:

Total transparency to the two successors, but invisible to everyone else. If people were to start thinking that I’m about to leave, they might stop listening to me.

This is the biggest danger in identifying—or strongly hinting—that there is a single preferred candidate by, say, creating a deputy CEO position without also announcing an imminent succession. “It can slow down decision-making because people don’t know whether to go to the existing boss or the future boss,” says Ader. It also limits the board’s options if a better candidate emerges (perhaps externally) or the anointed successor unexpectedly jumps ship.

Tell everyone only when it’s a done deal

So when should a company tell the world it has chosen a CEO successor? Ideally, at the same time as the incumbent CEO’s departure. If this isn’t possible—and the real world has a habit of thwarting a firm’s best-laid plans—a well-defined and clearly communicated succession process will give employees and other stakeholders comfort that the board will name the best candidate soon enough. A statement like, “We will now search for a suitable successor” following an executive departure is not reassuring in this regard.

When Microsoft announced in August that CEO Steve Ballmer would retire within the next 12 months, it also suggested that the succession-planning process had only recently begun; the board “has appointed a special committee to direct the process,” the company said at the time. When Deutsche Telekom announced in December 2012 that its CEO, René Obermann, would also leave within a year, it named CFO Timotheus Höttges as the eventual successor, putting any speculation swiftly to rest.

Although 12 months is a rather long time for a CEO-to-be to wait, it’s safe to say that the disruption and intrigue at Deutsche Telekom during the management transition paled in comparison to what Microsoft is currently experiencing, or what is beginning to emerge at Standard Chartered.