Looking back, a bond issue this week may have marked the high-water mark for the corporate bond boom. French utility EDF raised $700 million with a rare 100-year bond, the largest-ever issued by a European company, that will pay investors an annual coupon of 6% from now until 2114.

Over the past year, companies have tapped bond markets with gusto, raising a record amount of debt funding in the rush to lock in low interest rates. Now that interest rates are starting to creep up, bond issuance has slowed from its previous breakneck pace. It also doesn’t help that prominent investors are arguing that corporate bonds are “at their most overvalued level ever.”

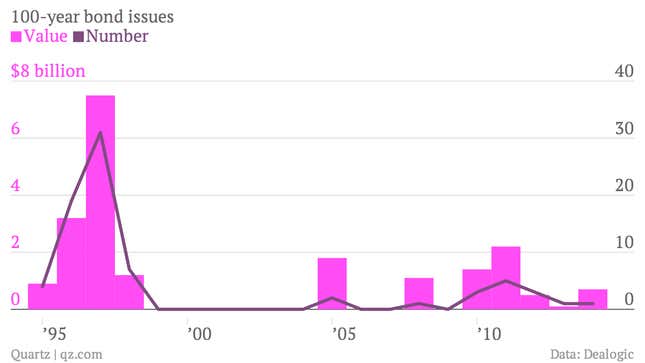

It takes a lot of confidence to believe that a borrower will continue paying interest for 100 years. But the attraction of ultra-low interest rates has spurred a steady drip of century-bond issues in recent years after a long drought. Around $6 billion in 100-year debt has been issued since 2008, double the amount raised in the previous ten years.

Century bonds are targeted at investors like pension funds and insurance companies, who look to match their long-dated liabilities with similarly long-lived income streams. But taking a punt on the health of a borrower 100 years from now can be daunting, which is why century bonds remain a niche market.

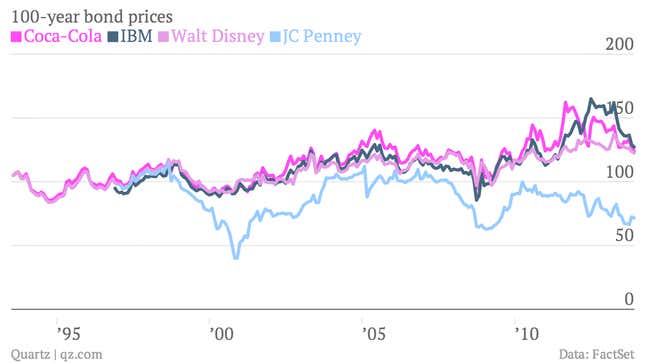

The century bond’s heyday was in the mid-1990s, when borrowers from Coca-Cola to IBM to Walt Disney borrowed for the (very) long term. Some of these bonds have worked out well for investors thus far; others, like JC Penney’s, have not.

Recent issuers of century bonds are concentrated in more conservative sectors than during the 1990s, including several universities like MIT, which borrowed $750 million in 2011. These institutions are a pretty good bet to still be around a century from now. A few of the other 100-year borrowers, like banks (Rabobank) and railroads (Norfolk Southern), seem like riskier propositions.

Rising interest rates tend to hit long-dated bonds harder than those with shorter durations (prices move inversely to yields), so EDF’s ability to find buyers for its issue just as rates start to rise and the appetite for corporate bonds begins to wane is admirable. However, the future state of the energy industry in the 22nd century is anyone’s guess, and whether EDF will still be around then to repay its debts requires an even bigger leap of faith.