Janet Yellen’s confirmation hearing showed signs that US monetary policy will soon adopt a third mandate. She said: “Overall, the Federal Reserve has sharpened its focus on financial stability and is taking that goal into consideration when carrying out its responsibilities for monetary policy.” While Yellen has traditionally downplayed this mission, the December FOMC meeting minutes also revealed a growing chorus of FOMC participants who believe that monetary policy should do more than just ensure full employment and price stability. Rather, they believe that monetary policy should look out for bubbles and pop them before they jeopardize financial stability.

At first glance, this sounds like a good idea. After all, who wants financial instability?

But back in 2002, Bernanke outlined several reasons why tightening monetary policy in response to bubbles is unlikely to work in practice. First, there’s no reason to believe that the Fed can accurately identify bubbles in advance. Second, even if a bubble appears, it’s not clear that raising short term interest rates could pop it. Third, even if monetary policy ends up bringing asset prices down, it is likely to do so only through hurting the livelihoods of average Americans.

Can the Fed identify bubbles?

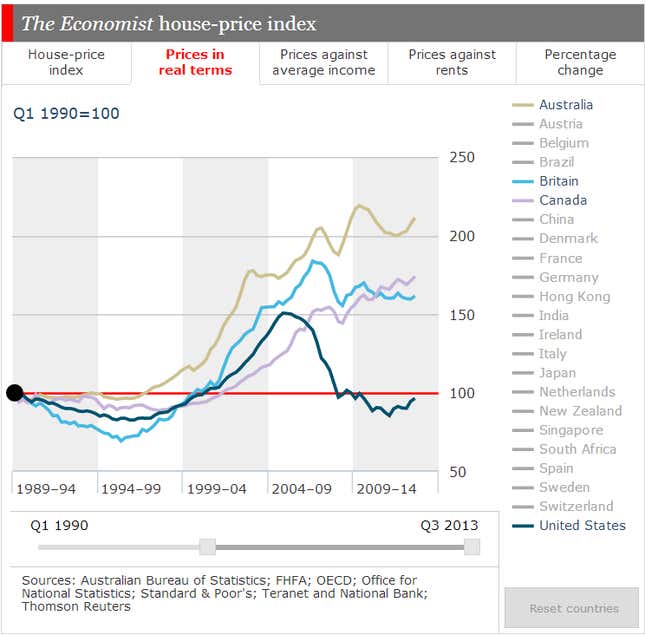

The standard example that people use when talking about financial stability is the housing bubble. According to the story, house prices were “clearly” on an unsustainable track, and as such the Fed clearly should have acted against the bubble in advance. Indeed, if you take a look at the graph of housing prices in the United States, the increase in housing prices is quite extreme.

But when we compare US housing prices relative to housing markets in other developed countries, this conclusion was not so obvious. As the Economist house-price index shows, although housing prices surged in Australia, Britain, Canada, and the US starting the early 2000s, only the American housing market sustained a severe crash. While certain other countries such as Spain, Ireland, and Denmark did have their housing prices fall, the bottom line is that even with the benefit of hindsight, predicting the crash in housing prices is not obvious. It is far too easy to trigger false-positives and see bubbles where there are none.

This false-positive is even worse if the Fed starts to look at other asset markets. The minutes for the December FOMC meeting reports that “several participants commented on the rise in forward price-to-earnings ratios for some small-cap stocks, the increased level of equity repurchases, or the rise in margin credit. One pointed to the increase in “issuance of leveraged loans this year and the apparent decline in the average quality of such loans.” These are all signs that investors are growing more optimistic about future growth in these asset classes, and some members of the FOMC are taking these to be signs of “irrational exuberance.” But given that financial markets are highly volatile, at any given moment there will always be certain asset classes that look to be in bubble territory. If the Fed were to redirect monetary policy on each of these warnings, it will inevitably end up fighting imagined demons.

Can monetary policy stop bubbles?

Even if the Fed has a hard time spotting bubbles, perhaps the cost of bubbles are large enough that the Fed still should take action. Yet there is no evidence that the Fed can do much to stop financial manias.

As a part of his Nobel Prize winning work, Robert Schiller found that volatility in stock prices could not be purely explained by volatility in the earnings of the underlying companies. Rather, there seemed to be a psychological factor influencing prices, causing prices to quickly accelerate upwards, and then crash back down afterwards.

Here’s the rub: if it really is market psychology that is driving up the prices of assets, it’s not clear why a few percentage point increase in short term interest rates can really pop the bubble. When people become “irrationally exuberant” about stock prices, they aren’t expecting single digit excess returns. They’re expecting maybe 10, 20, or even 30% returns—otherwise, there would be no bubble. In comparison, ever since the Great Moderation of the 1990s, the Fed funds rate hasn’t increased by more than 3% over the course of any one-year period. So by the time that a bubble is apparent, it’s unlikely that raising interest rates is enough.

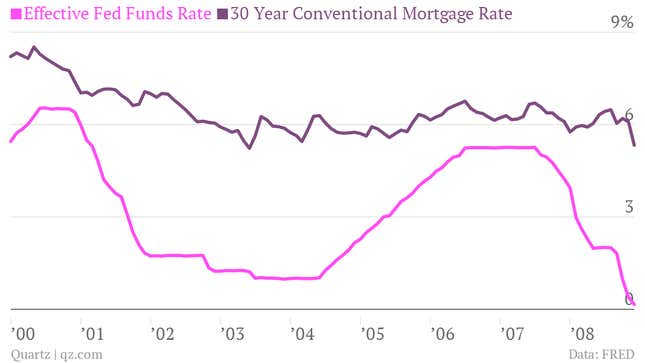

Research on the role of expectations in driving the housing bubble provides support for this interpretation. According to the Brookings Institute (pdf), one of the biggest drivers of the rapid growth in prices was that homeowner expectations of long-term price appreciation – around 10% — were too high. Moreover, even as the Fed started to raise interest rates in the 2004-2006, people still had relatively high long term growth expectations. Since 30-year mortgage rates were uncorrelated with the Fed funds rate, the Fed could have done little to change the path of house prices or the expectations thereof.

But not only do raising rates seem to have no effect on popping bubbles, it’s not even clear that low interest rates do much to cause bubbles. Monetary policy was quite easy during the ‘60s and ‘70s—a period in which the Fed was extremely tolerant of inflation, and as such real interest rates were relatively low. Yet that was also a period in which bubbles were not an issue. This certainly is not enough to be a causal, but it should give pause to anyone who thinks bubbles are just about easy monetary policy.

Some have argued that the Fed’s policy of keeping interest rates too low, for too long in the early 2000s spurred investors to look for more exotic financial instruments to earn a profit. This was the cause of the boom in mortgage backed securities and collateralized debt obligations that destroyed banks’ balance sheets. Hence, the Fed should be on guard against these kinds of financial innovations and pop those bubbles before they grow malignant. However, this argument fails for two reasons:

- We lack models for long term yields. The boom in mortgage backed securities was about the low rates on a long maturity asset: mortgages. So what this bubble theory is really saying is that the Fed’s easy monetary policy depressed long term interest rates in the early 2000s. But economists don’t really have a good model of long term interest rates. The majority of variation in long term bond yields is due to unknown factors that economists write off as “changes in discount rates.” As such, it would take a great hubris to justify tighter monetary policy on such an incomplete knowledge.

- Tightening is counterproductive. The biggest determinant of long term bond yields aren’t short term yields, but rather expected nominal GDP growth. If this is the case, the weaker economic conditions that result from bubble popping could lead to lower long term rates and spur a more intense search for riskier, higher profit investments.

As such, not only is monetary powerless to stop bubbles once they form, it’s not even clear that monetary policy plays a major role in causing bubbles to form in the first place.

The Risk of Overreaching

Of course, there is one surefire way that the Fed could quell asset price bubbles. If monetary policy drives the entire economy into a recession, of course households will lose enough income so that the bubble “pops” and asset prices collapse. But this would be a gross violation of the dual mandate for maximum employment and price stability and would do far more harm than good.

The Fed went down this exact self-destructive road for the mother of all booms and busts—the Great Depression. Bernanke went into great detail about this in his speech in 2002, and concluded that “the true story is that monetary policy tried overzealously to stop the rise in stock prices. But the main effect of the tight monetary policy, as Benjamin Strong had predicted, was to slow the economy—both domestically and, through the workings of the gold standard, abroad. The slowing economy, together with rising interest rates, was in turn a major factor in precipitating the stock market crash.” In the words of monetary history giants Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz: “the Board should not have made itself an arbiter of security speculation or values and should have paid no direct attention to the stock market boom.”

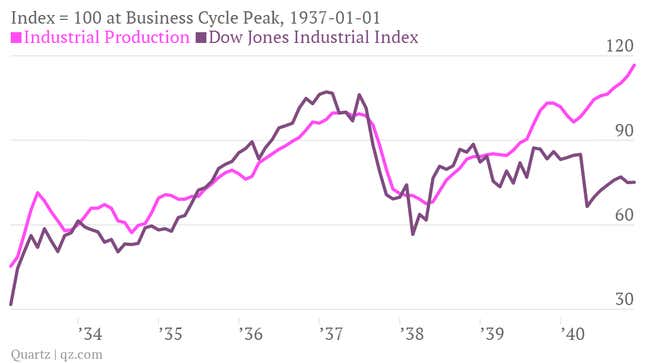

The Fed made the same mistake in 1936-37 when it doubled reserve requirements to tighten monetary policy. Harvard Business School Professor Julio Rotemberg documented this episode in his 2013 paper (pdf) “Penitence after accusations of error: 100 Years of Monetary Policy at the U.S. Federal Reserve.” At that time, banks were holding lots of excess reserves, and this led some people to think that the Federal Reserve was “pushing on a string,” and could do nothing more to stimulate the economy. Instead, a new fear arose that the banks would take all that extra cash and engage in “speculative purposes that would ultimately be costly,” while causing an “an uncontrollable increase in credit in the future.” And sure enough, tight monetary policy managed to drive stock prices down by 40%, but not without also causing a recession in which industrial production dropped by a comparable amount.

This lesson is particularly relevant for the United States right now, as reserves are high and the December FOMC minutes show that similar worries about financial stability are bubbling up. But the disastrous experience with the Great Depression, and the lesser recession in 1937, suggest that the Fed should instead keep its eye on the prize. Focus not on asset prices but rather on inflation and employment.

So how should the Fed address financial stability?

The Fed, however, can encourage financial stability through its role as a financial regulator. As such, if the Fed is concerned about financial stability, it could instead focus its efforts on regulatory policies to prevent debt buildups that would otherwise result in financial “fault lines.”

One important step that the Fed could take is to raise capital requirements for banks. What this means is that banks would be forced to finance more of their day-to-day operations through sales of equity, or stock, while shifting away from the current model that is based on elevated debt levels. This shift away from debt and toward equity would force banks to bear the consequences of their risk taking, thereby reducing the risk of a financial crisis when banks go belly up.

A key advantage of this approach is that it does not depend on the ability of the Fed to know when financial threats are arising. For monetary policy to pop bubbles, the Fed needs to have exceptionally good information (i.e. better than the information accessible by every other financial analyst) about what constitutes “excessive leverage.” But raising capital requirements and reducing debt makes the system as a whole more robust by reducing the incentives for excessive risk taking. The key idea here was described by Bernanke in his 2002 speech as “using the right tool for the job.” Given that monetary policy is more likely to overstep, the Federal Reserve should focus on specific financial regulations in order to stabilize the excessively aggressive, debt-laden financial system.

To ask the Fed to pop bubbles is like asking a blindfolded surgeon to remove a tumor with a chainsaw. The Fed is neither prescient nor precise enough to pop bubbles without risking even more severe damage to the broader real economy. With this in mind, the bar for intervention should be set exceptionally high.

Another allusion to medicine may be useful. “Above all, do no harm.” This maxim reminds us that before adopting a cure, it’s important to consider the side effects and ask whether the benefits truly outweigh the costs. And by this standard, the best thing that monetary policy could do for financial stability is to pay it no attention at all.