German automakers begin reporting earnings this week, and the picture doesn’t look pretty. New car registrations have fallen 10.8% in the euro area during last ten months, as increasingly wary and increasingly unemployed Europeans refrain from buying cars. With high debt levels—and facing tighter credit standards in the markets—some of those companies are looking more vulnerable to a European economic downturn.

But Germany’s car industry is not like the rest of Germany!—you might protest—which has escaped almost entirely unscathed from the sovereign debt crisis. Just look at the prices Germany’s government is paying to fund itself—a mere 1.6% for 10 years. And it has even issued two-year bunds (German federal bonds) with negative interest rates! Not to mention that German unemployment is at record lows: only 6.8% of the population is unemployed!

Slowly but surely, however, the shell that has protected Germany from the worst of the European crisis has begun to crack—and this may be the best thing that could happen for the euro. German car demand (a consumer indicator) is down 10.9% in Germany itself—not just elsewhere in the euro area. Unemployment rose for the sixth month straight in September. Banks have been under pressure for a long time, with high exposure to peripheral sovereign debt and continuing structural concerns exacerbated by the financial crisis. But the slow collapse of the auto industry—which accounted for 17.4% of the country’s total goods exports, its largest industrial sector—could be the first among many industries to succumb to declining demand and continued financial-market and policy uncertainty.

The “big three” automotive manufacturers—Daimler (which also produces the Mercedes-Benz line), Volkswagen (which also produces Audi), and BMW—are all likely to report that their earnings and sales fell this quarter from the last, and two of the three—Daimler and Volkswagen—have already warned analysts about sub-par outlooks ahead of their earnings announcements this week.

“We are gearing up for a challenging environment,” Daimler Chief Executive Dieter Zetsche told reporters last month. His plans to help Daimler stem the tide include cutting some €1.31 billion in annual costs, according to Bloomberg: good for the company’s balance sheet but bad for Germany’s economy. Zetsche also cut a deal with its workers to cut production at a major plant from two shifts to one.

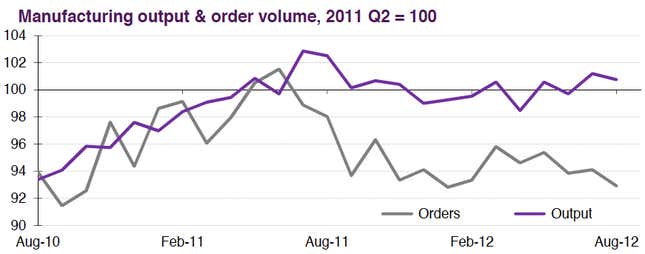

But investors have been wary of other German corporations, too. ”We think that the industrial outlook is getting gloomier. The September IFO manufacturing expectations fell to a new four-year low of 19.6, which suggests that German industrial production is likely to contract in the coming months,” explains Deutsche Bank’s Peter Reilly (see chart below). This—among other signs of cyclical weakness—has led Reilly and his team to caution clients against purchasing stock in electronics and engineering company Siemens, also Germany’s largest corporation by market capitalization.

Germany’s economy could deteriorate if slower growth at big corporations translated into decreasing demand for the parts needed to build their products, many of which are produced by the small- and medium-sized companies known as the Mittelstand. “Big companies are part of the reason the Mittelstand are such great exporters. Large German multinationals have always been willing to source components from small German companies,” explains Mario Ohoven, the president of BVMW, an organization which represents these smaller firms. “This gives our Mittelstand great exposure to overseas markets and drives both exports and innovation.”

Then again, the slow decline of Germany’s car companies—which have large operations outside Europe—suggests that overseas diversification only goes so far. Data compiled by Lombard Street Research suggests that German companies are already manufacturing more than they can expect to sell. If supply outpaces demand, companies will eventually be forced to cut back production, leading to layoffs and affecting the entire supply chain.

Mittelstand companies already appear to be picking up on the trend. While they said that they are better prepared to face the European crisis than companies elsewhere in the region, a full 75% of those surveyed by Ernst and Young LLP in August said they expected the crisis to get worse.

Not to say there isn’t opportunity in the downturn. Volkswagen has been taking advantage of high demand for relatively “safe” German debt—as opposed to, say, riskier French or Italian debt—issuing a €1 billion ($1.3 billion) bond in late August, agreeing to pay just a 2.375% coupon for 10 years. That has allowed its European market share to balloon to 24% at the expense of French rivals Peugeot and Renault. The number of new Volkswagens registered during the first half of 2012 still fell, but at a much slower rate than competitors’ cars. That’s probably because the company could offer better financing deals. Cheap financing has also allowed Volkswagen to invest €3.4 billion in Brazil.

Ultimately, however, a jolt to the German economy might be a good thing for the survival of the euro zone. Germany has remained the stubborn obstacle to progress made by euro area leaders—resisting politically unpopular efforts like bailouts, inflationary monetary policy, and any kind of debt mutualization—because the crisis hasn’t had a big impact on Germany itself. However, should German companies start shutting plants and slashing jobs, Germans and their southern peers might begin to see eye to eye.