We have just passed the 100-day mark until elections will be held for the European parliament. According to the latest polls, the self-hating parliament, as the head of a prominent think tank puts it, is about to do even more self-harm. Across the EU, voters are flocking to euroskeptic parties whose platforms emphasize taking back powers ceded to Brussels, if not dismantling the bloc entirely.

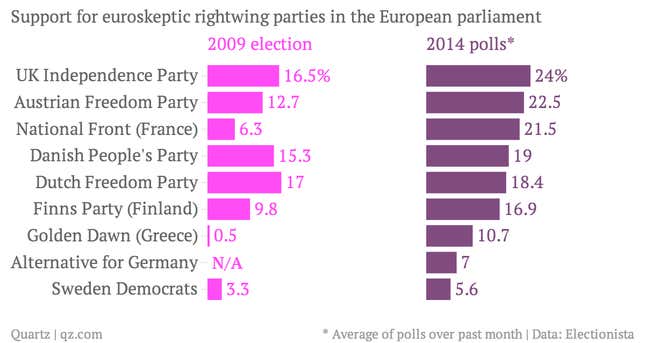

According to election-tracking site Electionista, which helpfully collects all of the latest poll data in an online spreadsheet, these mostly rightwing parties are poised to make big gains from their previous showings:

Does it matter? Insurgents from the political fringe have always been better represented in the European parliament than at the national level, thanks to low turnout and the perception that votes for the obscure, distant institution present an opportunity to protest without serious consequences.

But what’s different this time around is that the rightwing insurgents seem serious about teaming up (pdf), which would give them more clout in the parliament. At the same time, the parliament has acquired more power and prominence, not least the ability for the largest party group to pick the next president of the European Commission, the EU’s influential executive arm.

But even if the anti-EU populists double their ranks in the parliament, from around a tenth of seats today to perhaps a fifth after the elections, it won’t be enough to outnumber the mainstream groups. What’s more, anti-EU parties have a checkered history (pdf) of cooperation, so internal cohesion is far from certain.

A right turn, and the road ahead

Still, there are still important consequences of the European parliament’s lurch to the euroskeptic right. In the European parliament, a sizable share of representatives bent on the EU’s demise will put the onus on mainstream parties to limit their bickering, lest nothing gets done and the obstructionists win by default. This could redefine the debate over the EU’s development, pitting those who would deepen it against those who would destroy it; a lot of nuance is lost when legislation is pitched in such stark terms.

At the national level, leaders may fear that voters will get a taste for voting against the establishment beyond the European parliament. The British Conservative Party’s promise for a referendum on EU membership reflects this worry, as the far-right UK Independence Party steadily picks off its supporters. The recent anti-immigration referendum in Switzerland, with a similar vote in the works in Norway, provides additional fodder for rightwing parties inside the EU to agitate for similar initiatives at home.

A lot can happen between now and May, particularly for insurgent political parties that are combustible at the best of times. But what is clear is that the European parliament is no longer an irrelevance, and its upcoming elections will be one of the European project’s biggest tests to date.