There is more to Switzerland’s anti-immigration vote than meets the eye

Any Swiss citizen who collects 100,000 signatures can put an initiative to a national referendum. This brand of extreme direct democracy is unique on this scale, and has generally served Switzerland well—certainly in comparison with other referendum-driven systems, such as California’s.

Any Swiss citizen who collects 100,000 signatures can put an initiative to a national referendum. This brand of extreme direct democracy is unique on this scale, and has generally served Switzerland well—certainly in comparison with other referendum-driven systems, such as California’s.

But the perils of turning voters into legislators became clear over the weekend, with the narrow passage of a referendum that calls for curbs on immigration from the European Union. EU officials are not pleased, noting that restrictions on the free movement of people will also hinder trade in goods, services, and capital between the bloc and Switzerland. The agreement allowing free movement of EU nationals came into effect in Switzerland in 2002, along with a host of other bilateral agreements to liberalize trade with the EU, by far Switzerland’s largest trading partner. Swiss business groups lined up against the referendum (paywall), warning that it would harm the competitiveness of internationally-minded companies such as Nestlé, UBS, and Roche.

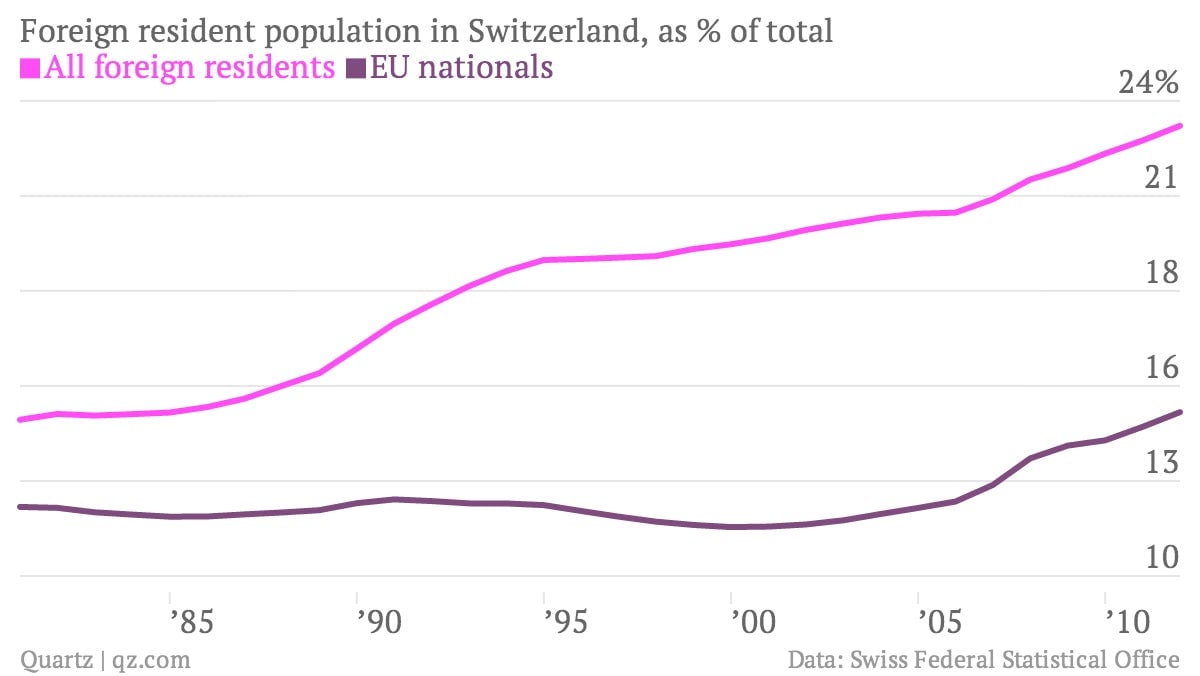

Foreigners comprise nearly a quarter of Swiss residents, with the majority coming from EU countries:

The EU immigration cap was the brainchild of the rightwing Swiss People’s Party, which claims that the country is “bursting at the seams.” Before yesterday’s vote, previous attempts to put hard limits on immigration via referendums all failed at the ballot box. The recent rise in anti-immigration sentiment in Switzerland is part of a growing trend across Europe, with anti-immigration parties hailing the Swiss vote as a harbinger of a broader backlash against Europe’s open borders.

But anyone who thinks that Switzerland is lurching headlong to the right is mistaken. For observers in countries with only two or three major parties, such as the US or UK, Swiss voting patterns can seem confounding because they do not conform to the usual bundles of social and economic policies associated with the left and right. In two other votes held alongside the immigration referendum, voters supported, by wide margins, seemingly liberal proposals—to expand railway funding and reject a proposed ban on health insurers covering abortion. At the same time, notions of Swiss voters’ pro-business bent—voters previously rejected a cap on executive pay and an extension of mandatory vacation leave—were also confounded by the anti-immigration vote.

Perhaps it is not surprising that a country with powerful cantons (states) and a weak federal council, three official languages, and a vast array of political parties can be tricky to analyze using the traditional political calculus. Thus, the right-leaning parties elsewhere in Europe that praise the Swiss vote restricting immigration might want to hold their applause. Considering what else the electorate has passed in recent years, they may find that those outcomes clash with other aspects of their platforms, especially on social and welfare programs. When the people speak, their beliefs are often much more nuanced than politicians give them credit for.

A selection of voting results in recent Swiss referendums:

FOR

- Limits on immigration from the EU (Feb. 2014)

- Expansion of public funding for railways (Feb. 2014)

- Binding shareholder vote on executive pay, and ban on signing bonuses, severance packages and merger-related bonuses (Mar. 2013)

- Restriction on building of second homes to less than 20% of housing in a community (Mar. 2012)

- Ban on construction of new minarets (Nov. 2009)

AGAINST

- Ban on coverage of abortion by health insurers (Feb. 2014)

- Cap on executive pay to no more than 12 times the average worker’s salary (Nov. 2013)

- Ban on military conscription (Sep. 2013)

- Extension of mandatory annual vacation leave from four to six weeks (Sep. 2012)

- Storage of guns at public arsenals instead of homes (Feb. 2011)