A year after a controversial bail-out put an end to Cyprus’s financial crisis, it is still a major offshore banking center for Russian cash—which is just the way the country’s leaders want it.

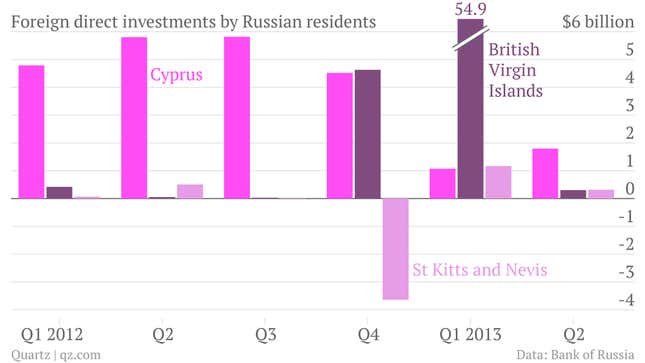

Cyprus is creating shell companies at rates higher than before the crisis—1,454 in January alone—and a look at the most recent financial outflow data for Russia confirms that even after a financial rescue in which bank depositors took a loss, nearly $2 billion headed for the island. It remained, along with two other tax havens, among the top three destinations for Russian foreign investment in the first half of 2013:

This time last year, the country was heading to the top of the financial crisis panic charts; the tiny Mediterranean island cum offshore banking center had invested heavily in Greece and its banks were failing. When European Union authorities came to the rescue in March, they didn’t want to bail out Russians who had “invested” billions in the country to avoid taxes and official scrutiny in their home country. So they decided that depositors with more than the eurozone-insured €100,000 ($138,000) would take significant haircuts.

Some observers incorrectly feared banks runs would result from a measure to force a bank’s creditors to share losses with the citizens who typically bear the brunt of a financial rescue. The precedent they likely really feared was that lenders in central Europe would be put on the hook for unwise loans to the periphery, but regardless of their fears, in Cyprus—as in other historical experiences—a bail-in helped put an end to the financial crisis, if not the resilient offshore banking. What does that tell us?

Secrecy is as important to a tax haven as its tax laws.

Though Cyprus nudged its corporate tax rate up to Irish levels and tightened capital controls, the ability to set up a shell company in a European Union tax haven is key, even if the actual money may not end up in Cypriot banks but passes through to other financial systems. And, since the IMF has approved the country’s plan to lift its capital controls by the end of the year and Russians now own the country’s largest bank, you can expect deposits to surge upwards again.

Russians don’t trust their financial system.

Wealthy Russians with the means to do it are still sending their money abroad, even to a place where the banking system almost collapsed, rather than keeping it at home, where a rather capricious government might seize it.

Tax havens don’t necessarily benefit the locals.

Cyprus’s citizens are still facing high unemployment (17.5%) and little in the way of growth prospects, while local bank lending has tightened considerably. Building a financial system to serve foreign clients first doesn’t necessarily improve a country’s fiscal condition, as fiscal collapses in places like the Caymans have shown before. While Cyprus’s policymakers have rushed to restore the banks, social welfare programs haven’t bolstered the fortunes of the country’s austerity-wracked citizens.