The failure of the Mt. Gox exchange isn’t the end of bitcoin—but it’s probably the end of amateur hour.

Now bitcoin firms connected with blue chip venture capitalists and Wall Street are moving to control bitcoin’s infrastructure and integrate it into the regulated financial system.

Mt. Gox was once the biggest online exchange for converting bitcoin into dollars and back, but shut down operations after a flaw in its software made it possible for hackers to steal the digital currency. When some 744,408 bitcoin it held on behalf of customers turned up missing—worth perhaps hundreds of millions of dollars—the Tokyo-based company became insolvent.

In an echo of the 2008 financial crisis, Mt. Gox essentially tried to declare itself “too big to fail,” according to a document purporting to come from the exchange. The document was leaked by one bitcoin entrepreneur and is as yet unverified, though it jibes with most press reports. (Update, Feb 26. Mt. Gox CEO Mark Karpeles describes the document as “more or less” legitimate and a “draft…of proposals to deal with the issue at hand.”)

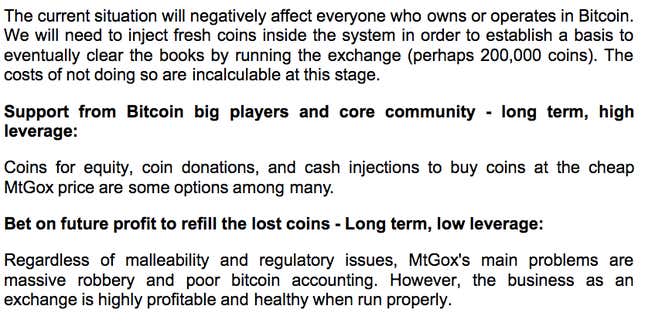

It depicts a scenario that plays out in the financial markets too often for comfort. A troubled financial institution scrambling for help argues it is so important to the financial system—the bitcoin ecosystem, in this case—that its bankruptcy would bring down the whole system. From the document:

What Mt. Gox allegedly wanted was a bailout, like the one JP Morgan arranged for the largest banks during the panic of 1907 or the ones put together by the US government after the 2008 financial crisis. Possible strategies above include a debt-for-equity swap, capital injections, and even the equivalent of preferred shares—anything to restore solvency with the promise that future profits will make up the difference. But there are no clearinghouses between bitcoin customers and their exchanges, there is no central bank for bitcoin, and its major players apparently will not bail out Mt. Gox.

The absence of a rescue for Mt. Gox is good if you like to see incompetence (and Mt. Gox’s management has been troubled for years) punished by the markets. It’s unfortunate if you lost your cash in the process, whether it was stolen or simply as bitcoin value dribbled away during the resulting sell-off.

Bitcoin adherents are channelling Henry V to bolster faith in the currency, which has fallen in value perhaps 20% after Mt. Gox was shuttered. Strip away the drama, however, and they are right that the exchange’s failure doesn’t spell doom for the whole system even if confidence in the currency slips temporarily. And bitcoin, like all means of exchange, depends on public confidence.

But what will restore that public confidence? Five bitcoin firms backed by venture capitalists and plugged into Wall Street have responded to the crisis with a coordinated promise to support “transparent, thoughtful, and comprehensive consumer protection measures.” Second Market, the company that came into existence as a private trading floor for Facebook stock, has announced plans to create a bitcoin exchange, not for anyone on the internet, but for major financial institutions on Wall Street. And if large financial institutions get involved with bitcoin, you know what that means: regulators are not far behind.