“There are only two important people in the wine business—the winemaker and the wine drinker. Right now, they’re both getting screwed.”

Rowan Gormley doesn’t mince words. The founder of Naked Wines, part venture capital firm and part wholesale buying club, has little time for the wine industry’s traditional ways. This might be because he’s an accountant by training. But his background belies a deep appreciation for wine, and a missionary’s zeal for rewriting the rules of how the product gets from grape to glass. He thinks he can apply his financial background and some fresh thinking to shake up the established order in an old-fashioned, exclusive, and often incestuous industry. So far, it seems to be working.

From spreadsheet jockey to cellar dweller

Although he got his start crunching numbers at Arthur Andersen in his native South Africa, Gormley made his way to the UK with a private equity firm and, later, helped launch the online wine retailing arm of Richard Branson’s Virgin Group. In 2008, Gormley and a group of his former Virgin colleagues founded Naked Wines in the UK, a week after Lehman Brothers collapsed and threatened to take the global economy with it. “This forced us to be radical, to turn the conventional wisdom on its head,” Gormley says. How radical? This is how he puts it:

The astonishing thing about the wine business is that there isn’t a bottle in the world that can’t be made for about £10 [$17]. So there isn’t a bottle of wine that should cost more than £20. That’s what we want to do—take wines that others are charging £50, £100, or £300 and sell them for £20.

Other industry observers generally concede this point, and copious studies show few links between a wine’s price and its perceived quality. British wine writer Jamie Goode reckons that ”a £10 wine will likely afford you a significantly better drinking experience than a £5 wine, but each increment in quality beyond this will cost substantially more.” Beyond £20 per bottle and the “cost of wine is largely distanced from production costs,” he writes.

Wisdom of the crowds

Naked Wines pitches itself as a “customer-funded wine business,” with buyers who pay a monthly minimum into their accounts—$40 in the US, £20 in the UK, and A$40 in Australia—earning the right to get a discount on the wine the site sells. These recurring payments add up until customers see a bottle they like, at which point they dip into their balance (and add more, if necessary) to buy wine at discounts of at least 25% off the retail price. Anyone who doesn’t deposit the minimum monthly amount can still buy the site’s wines, but only at the full price and sometimes after a delay, with regular depositors getting first dibs on certain ranges.

The company describes these regular payments as investments—and its customers as “angels,” borrowing from venture capital terminology—because it uses a chunk of these proceeds to pay independent winemakers upfront to produce a batch of barrels, covering the cost of making wines for sale exclusively via the site, which also earns them royalty fees.

Naked Wines makes its money by negotiating rates with winemakers that reflect its role as, in essence, an early-stage investor providing risk capital; this results in a decent margin on the final sale of a bottle, even as the discounted price looks like a bargain against wines whose costs are inflated by the industry’s traditional overheads. The site also benefits from the bulk of its customers essentially pre-paying for the bottles they buy via the regular deposits they make to maintain angel status.

Share the wealth

In many ways, the Naked Wines model is to wine what Made.com is to furniture, Everlane is to fashion, Warby Parker is to eyeglasses, and other disruptive direct-sales sites are to a wide range of other consumer industries. To varying degrees, these firms bypass distributors and other middle-men, eschew traditional marketing practices in favor of social media campaigns and word-of-mouth buzz, and generally bring producers closer to consumers. (Gormley describes his job as taking care of ”all the boring crap in the middle” of the wine-buying process.)

Ideally, this benefits both sides—the markups that once went to distributors, retailers, and other gatekeepers are instead shared between maker and buyer. Put another way, they are no longer getting screwed.

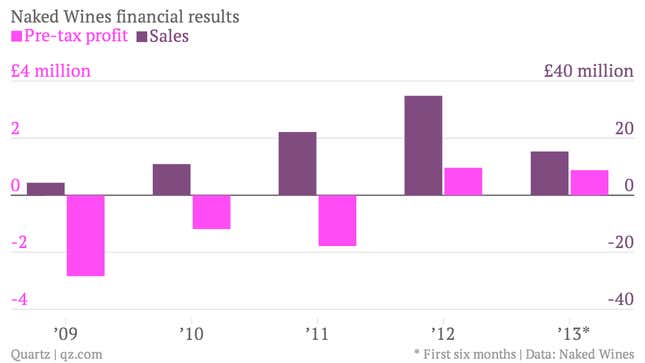

By the time Naked Wines expanded into the US and Australia in 2012, it had already turned its first operating profit, making £1 million on £35 million in sales. This is hardly a world-beating margin, but consider that the company only employs around 50 people. And the firm now has 200,000 angels, implying annual revenues of around £50 million from the minimum monthly payments alone.

From farm to table, grape to glass

Echoing the farm-to-table movement in the food industry, Naked Wines treats wine and winemaker as a package—the appeal of the maker is integral to the allure of what they make (and is branded as such.) Artisanal, small-batch production by one-man bands also taps the same zeitgeist that draws people to sites like Etsy to buy handcrafts.

This plays into another important aspect of Naked Wines’ model—this being 2014, the site features plenty of social elements. Ratings, comments, and forums give buyers a chance to chat and compare notes. Some 2.5 million customer ratings also provide the company a comprehensive view of wine-drinkers’ tastes, which reinforces Gormley’s opinions on the disconnect between price and quality.

Crucially, the winemakers themselves also participate in these conversations, providing access unheard of for buyers of bottles from big estates in Napa or Bordeaux. Stripping away the layers separating the vintner from the drinker is what inspired the company’s “naked” moniker, and what it says gives it an edge over monolithic brands that lack a similar personal touch.

The company also taps the loyalty and sense of shared purpose with its customers in other ways. The firm’s initial equity funding came from WIV Wein International, a German family-owned firm that specializes in wine retailing. The money that the company collects from angels each month mostly goes towards funding wines that take a year to make. But over time, customers tend to trade up, Gormley says, seeking special and rare varietals that are more expensive and time-consuming to make. The company needed to raise long-term financing to match the working capital cycle for wines that might take three years from harvest to bottling. To this end, in September last year it decided to issue a rather peculiar brand of bond.

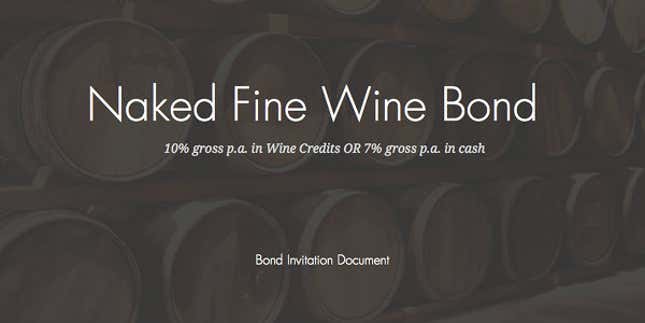

The bond that pays interest in Chardonnay

It dubbed the issue the “Naked Fine Wine Bond” and offered it directly to the public in lots of £500 to £10,000, with interest paid at the end of its three-year term. It tweaked the bond’s structure so that investors could choose to receive the equivalent of 7% annual interest in cash or 10% in credits toward buying wine on the site, with preferential access to the particular vintages financed by these funds. Gormley says that it was clear the issue would be oversubscribed within a week of its four-week offer period. The firm upped its initial fundraising target from £3 million to £5 million. Gormley says he would be surprised if the majority of investors didn’t opt to be paid in wine instead of cash.

This added a peer-to-peer lending element to the Naked Wines business model, to go with the Kickstarter-inspired way that its customers fund winemakers in exchange for preferential access to their products. In the same way that the company operates outside of the traditional channels in selling its wine, its own financing has largely skirted the banks and other established financial services firms. Given the scarcity of business loans extended by Europe’s fragile banks, this avoids the headaches of trying to cajole credit from a traditional lender; on this point, Naked Wines is far from alone among companies in the UK or elsewhere in Europe.

Gormley says he will use the proceeds of the bond to “go up a notch in terms of the quality of wines we are working with.” This means signing up more top winemakers to join the Naked Wines stable.

Heard it through the grapevine

Wayne Donaldson has been in the wine industry for nearly 30 years, including high-ranking positions at the famous houses of Chandon and E&J Gallo. Not long after he set up his own consulting business, Naked Wines came calling, seeking his expertise in sparkling wines. He had left that world behind after leaving Chandon, but the upfront funds enticed him to return; he used the money to buy grapes and hire equipment in Sonoma for his first run of bubbly, 5,500 cases worth, which went on sale last year.

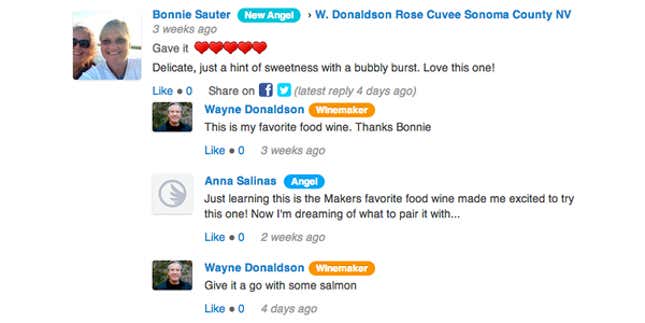

Donaldson’s top-ranked variety currently has a 91% approval rating, and on some days he gets 100 emails from customers (and diligently responds to them all). This is a typical interaction with customers on the page for his sparkling rosé:

“I use the platform to solicit as much information as I can,” he says. He won’t necessarily alter his process unless the average ratings drop below 80%, but even an experienced hand like Donaldson appreciates the continuous feedback that the site makes possible. In corporate winemaking, focus groups were a useful window into consumer tastes, but the conclusion from these sporadic, artificial exercises was sometimes difficult to interpret. Donaldson recalls one session in which a group praised a wine’s raspberry tones, which neither he nor any of his team who actually produced the wine could detect. It made for an ”interesting translation” exercise when it came time to brand the wine.

But can you make a living from selling bottles of bubbly for $11.99? Donaldson says that the bulk of his income still comes from consulting; if all goes well, the wines he sells through Naked Wines could one day account for a half of his earnings. And even this is not assured. The quality of winemakers funded by Naked Wines has been rising, he says—in the industry, the site was once known to “generally say ‘yes’ to everything, but now not everyone can get into it,” he notes. “It’s becoming pretty competitive, and narrower in terms of winemakers’ skills.”

Off the beaten track

When you ask Gormley for tips on what to drink, he simply recommends you “think of all the famous wine regions in the world and then ignore them.” Even as his empire grows, this principle remains at its heart—supporting the unknown winemaker from an unheralded region is core to the site’s philosophy. As an underdog itself, Naked Wines bills itself as a champion of the authentic and affordable, as a place to find undiscovered gems. Of course, there is also a commercial logic to fostering this image, since it’s cheaper to finance winemakers who ply their trade off the industry’s beaten track.

In many ways, Benjamin Darnault is the poster child of the Naked Wines business model, making his name on the site on the strength of his story.

Not long after Naked Wines was founded, Darnault approached Gormley with an idea. The Languedoc region of France is known primarily for producing ordinary wines in bulk, but the young winemaker thought that some of the local grapes, like carignan and cinsault, were given short shrift. His idea was to source grapes from the region’s oldest vines, saving them from the ignominy of getting mixed up in pots to make cheap table wines.

He used the funds from some of Naked Wines’ first angels to pay local growers to set aside their best grapes. “Not many people pay them up front, so it gave me power and made people take me seriously,” he says. Darnault was voted the site’s favorite winemaker in 2011, and has a cult following on its message boards.

“I had no idea where it was going to go, but now I’m selling more than half a million bottles,” he says. “When you type my name in the internet, there are more results than for a lot of people who are much bigger winemakers.” This, in turn, has given him the credibility to launch a consulting business alongside his winemaking duties.

A world of possibilities

In an industry famous for its snobbery, Gormley is aware of the dangers of believing his own hype. “We have the best model we’ve thought of so far, but what keeps me awake at night is whether somebody else has thought of a better one,” he says. And the business has its detractors, both in terms of the quality of its wine as well as its emphasis on “investments,” “angels,” and other marketing buzzwords that one scathing reviewer thought added up to little more than “smoke and mirrors” obscuring a run-of-the-mill wine buyers’ club.

But what isn’t at issue is the fact that the site embodies the spirit and practices of many other consumer-facing businesses born over the past five years—the internet has exploded the choices now available to consumers and eased the route to market for producers, while social media brings buyers and sellers closer than ever. Amid the noise, fads, and failed experiments, the value of novelty and variety grows in importance, with big brands struggling to control markets as the barriers to entry collapse. And it is telling that the fusty wine business is now succumbing—at the hands of a relative newcomer with a background far from the norm in the industry.

This is fitting. “For years, the wine industry has made people feel like outsiders,” Gormley says. “We make them feel like insiders.”