The hemlock woolly adelgid hails from Osaka, Japan. When it moved to the US in the 1950s, it settled right in, facing no natural predators and feeding off the buffet of hemlock forests lining the eastern coast. Similarly, the gypsy moth, a European emigre, now gobbles up the leaves of millions of acres of trees (pdf, p.5) each year. And the emerald ash borer, a beetle of Eurasian extraction, has killed millions of trees in North America in just over a decade, earning it the title of “worst forest problem in our lifetime” from a Colorado State University entomologist.

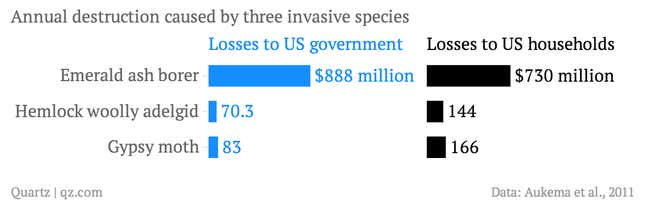

Together, these creatures now cause around $2.1 billion in economic losses in the US each year. But they really don’t like the cold, it turns out. In fact, the one good thing about the unrelenting cold weather this winter is that it appears to be decimating the populations of destructive invasive insects that cost the US government and homeowners billions each year.

“This winter has been a godsend for the hemlock. Overnight temperatures dipped to minus 15 [Fahrenheit, or -26°C] here in Amherst [Massachusetts], and that’s cold enough to guarantee almost complete adelgid die-off,” Joseph Elkington, a professor atthe University of Massachusetts, Amherst, told the Worcester Telegram.

Elkington says that in some parts of North Carolina, subzero temperatures have killed 100% of the adelgids. In Massachusetts, around 80% of the population should die, according to a state official. Gypsy moths and emerald ash borers are similarly vulnerable to extreme cold; the US Forest Service estimates that 80% of Minnesota’s emerald ash borers died in January. Other invasive insects, such as the southern pine beetle, which has been ravaging New Jersey, and the Asian stinkbug, may be dying off as well.

Unfortunately, this is a kind of meteorological booby prize. The same extreme weather that may be causing polar vortexes is also making winters warmer on average—and that’s letting these insects live further and further north, making increasing swaths of the US hospitable to invasive species, which cause $143 billion in economic losses in the US each year.

“Before this winter we had a couple of milder winters, likely representative of what will happen in the future, and the adelgid took off like gangbusters and killed a lot of hemlock in a matter of a couple of years,” Elkington said. Those warmer winters will likely push the adelgid further north still, into Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine.

The cold may also kill off predator insects that forest officials have been releasing to take out invasive insects. For instance, parasitoid wasps that are supposed to control the emerald ash borer population in Michigan and other states are even more vulnerable to the cold than their prey, whose populations might recover more quickly as a result.