Demon shrimp and other invaders are costing the UK $3 billion a year

It’s scary times for British shrimp. Since 2010, they’ve been battling a foreign amphipod whose habit of killing and maiming for fun earned it the nickname “killer shrimp.” Now they face destruction at the claws of a bigger, meaner menace that hails from the east. So pervasive are these new invaders, which scientists have dubbed “demon shrimp,” that they threaten to completely wipe out the locals, says Alex Ford, marine scientist at the University of Portsmouth.

It’s scary times for British shrimp. Since 2010, they’ve been battling a foreign amphipod whose habit of killing and maiming for fun earned it the nickname “killer shrimp.” Now they face destruction at the claws of a bigger, meaner menace that hails from the east. So pervasive are these new invaders, which scientists have dubbed “demon shrimp,” that they threaten to completely wipe out the locals, says Alex Ford, marine scientist at the University of Portsmouth.

“They are out-eating and out-competing our native shrimps and changing the species dynamic in our rivers and lakes,” said Ford, who is working with the UK Environment Agency to tackle the problem. “As soon as one species is depleted it can affect the whole food chain with potentially catastrophic results.”

The closely-related demon and killer shrimp varieties come from the Black and Caspian seas; they’re thought to have travelled to the UK via ballast water, which ships take on to manage their cargo weight.

The problem is that local predators and parasites haven’t evolved to keep that species in check. New species also introduce alien parasites to which local varieties aren’t immune. Ford is currently investigating whether the foreign shrimp are also carrying “demon parasites,” as he put it.

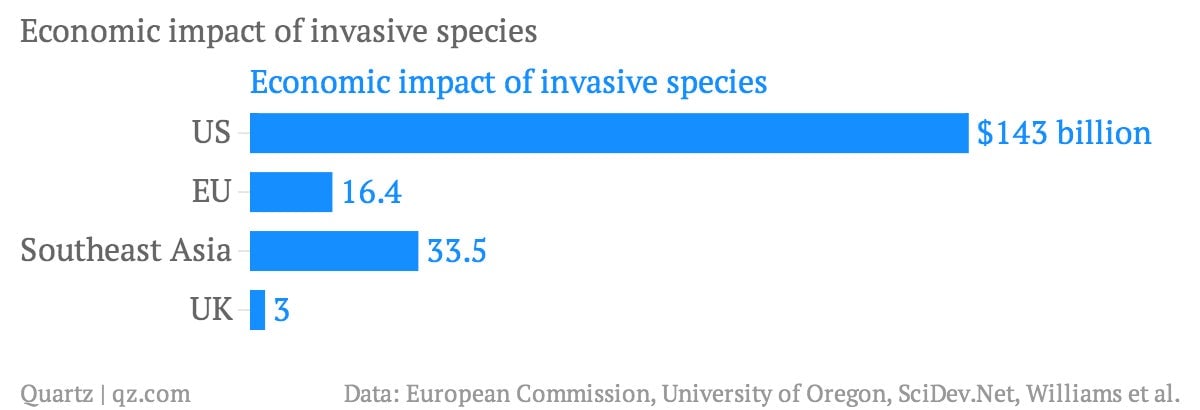

The existence of such parasites would be costly. Losses caused by invasive species like demon shrimp now total around £1.8 billion ($3 billion) a year in the UK. And other countries have it worse:

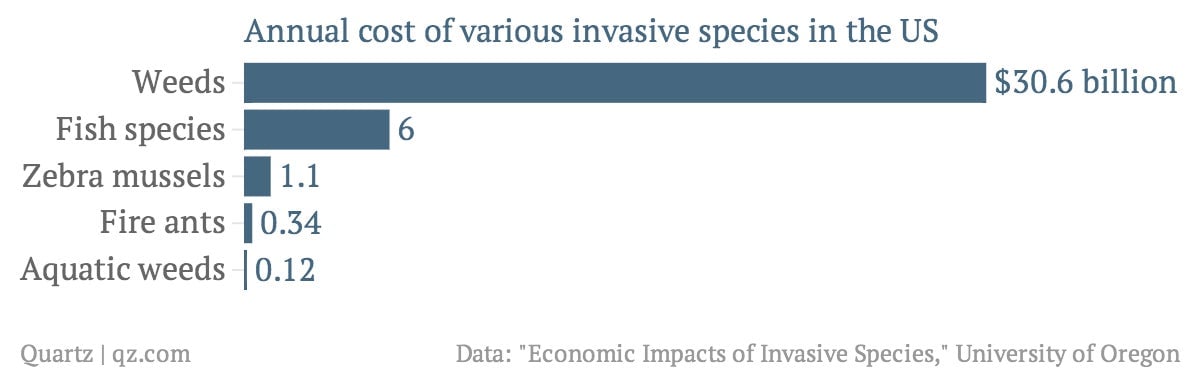

Countries or regions with big agricultural or aquaculture sectors—including the US and Southeast Asia—typically get hit hardest, as you can see. Here’s a breakdown of some of the worst offenders:

Neither killer nor demon shrimp have made it to the US yet. But if they do, fellow invaders from their native Ponto-Caspian region will probably make their transition easier. That’s because of a phenomenon that scientists call “invasional meltdown” theory—when the invasion of one non-native species changes the ecosystem in a way that facilitates the population growth of other alien species. For example, when zebra mussels took over the Great Lakes in the mid-1980s, they ate so much phytoplankton that they cleared the way for the extra sunlight needed for Eurasian milfoil algae to explode. Scientists prophesy that zebra mussels, which also hail from the Ponto-Caspian region, will help shrimp emigres (pdf, p.53) to the US dominate the Great Leaks as well.