There are more than 1.5 million workers making products for Apple, and some of them are children.

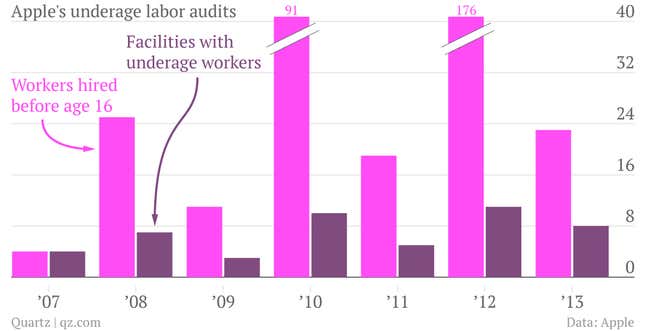

The company knows this, and it will tell you: In 2013, it audited 451 different facilities in 16 countries, and found 23 people who had been hired when they were younger than 16. Eleven were still underage at the time of the audit. In all of its publicly available audits, from 2006 to 2013, the company has found 349 child laborers.

What happens after they are found?

The dark crevices of the supply chain

There could be as many as a dozen different suppliers between raw materials and the finished iPhone, iPad or Macbook you hold in your hand. The most responsible companies look perhaps two or three steps down, supply-chain responsibility experts say.

In 2010, Apple’s reliance on this mostly-foreign supply chain led to the worst public-relations scandal in its history: A spate of worker suicides highlighted the conditions at Chinese factories run by Foxconn (a.k.a. Hon Hai), the Taiwanese manufacturing giant. No matter that Apple wasn’t the only company that hired Foxconn to build its products—HP and Dell do too, among others—success made it a target, as customers began to ask where their magical devices came from.

This forced Apple to begin a long process of improving how it monitors its supply chain. In 2006, the first year it began auditing suppliers, Apple looked at 11 factories and didn’t have a program to train suppliers in its labor standards; in 2011 it visited 229 and had trained 1.5 million managers and workers. By 2012, Foxconn pledged to end the 100-hour work-week and adopt some minor wage hikes.

The same year that Foxconn’s suicides became news, Apple discovered 91 underage workers in the factories making its products. Forty-two of them were found at a single facility in China that had partnered with a vocational school which forged hiring papers. You can see how it drove up the numbers in the chart above. Apple promptly stopped doing business with the company and reported it to the government. A similar incident contributed to an even bigger spike in 2012 (more on that in a bit).

Think of the children

But firing the supplier was clearly not enough, given the questions the company was facing. Its executives decided to adopt a program designed in 2008 by Impactt, a social-responsibility consultancy based in the UK that operates in China, India, and Bangladesh. The plan calls for Apple to make any transgressing supplier pay not only for the education of any child laborers it is found using, but also keep paying them wages until they graduate (thus removing their incentive to stay out of school). Apple follows up with the former workers to ensure they are still in school.

The idea is to deter suppliers from hiring children, while making sure any they do hire end up back in school. Dionne Harrison, who manages these programs for Impactt, says her local staff go to the factory to meet the workers, figure out their actual age and, eventually, meet their families, in an effort to convince them to go back to school.

It sounds like a good deal. Yet most of the time, the young workers don’t take it.

A 34% participation rate

Apple executives declined to discuss their child labor policies with us or say how many underage workers have entered the remediation program, which a spokesperson confirmed began in 2010. Impactt manages Apple’s program along with those of two other companies; in its most recent report (pdf), the consultancy said only 34% of the child workers offered the chance to participate in the program in 2011 went back to school. Harrison says the participation rate is about the same today. Before 2011, it was even lower; from 2006 to 2010, only 60 of 330 children found working in factories in China, India, Turkey, Vietnam and Bangladesh returned to education.

Why not take the stipend and the schooling? Sometimes, by the time auditors discover a worker was hired as a child, she is already of working age. Other times, the underage laborers don’t like school and prefer to work. But there’s also the rising pressure to earn more money. In China, as the economy grows with more and more foreign production, the cost of living has in the last decade started rising faster than wages. “In terms of workers feeling the pinch, they feel it much more now than they’ve ever done before in China,” Harrison says.

The problem of child labor

Rising wages have put pressure on manufacturers to move inland, automate, or even get out of the country altogether. But for second- and third-tier suppliers who don’t have those options, cheaper labor may be all that’s left. It’s “one of the reasons you see an increasing number of dispatched workers or workers on these so-called internships,” Dan Viederman, the CEO of Verite, a consultancy that works with Apple to resolve problems with migrant laborers trafficked into sub-contracted factories. Child laborers can wind up working far from home, as part of the wave—now gradually receding—of workers heading from the Chinese heartland to coastal factories.

That’s one reason that Asia remains the world leader in child labor—though there as in other regions, the phenomenon is declining, thanks to industrialization. (Of the one in 10 children around the world who work, most are subsistence farmers.)

In Apple’s most public child-labor incident—and the only one to date where it has named and shamed its supplier—auditors discovered in 2012 that a company called Guangdong Real Faith Pingzhou Electronics had hired 74 underage workers after a labor agency, Shenzhen Quanshun Human Resources, helped families forge proof-of-age documents for their children. Apple terminated its contract with the supplier, and made the company return the children to their families, as well as offering them its remediation program.

Apple publicized the case, seeing an opportunity to warn suppliers, improve its public image, and ding competitors. “If they’re not finding [child labor], they’re not looking hard enough,” Apple’s SVP of operations told Bloomberg last year.

One Apple competitor, Samsung, the largest manufacturer of phone handsets in the world, said it found no underage workers (pdf) in its factories in 2012. The company didn’t respond directly to questions about how it addresses child labor, but it said that because 90% of its parts are made at its own facilities and not outsourced, it can “offer world-class working conditions and maintain the facilities in accordance with international labor standards in all regions in which it operates.”

Labor activists dispute that: In 2012, the NGO China Labor Watch found eight facilities (pdf) either directly owned or contracted by Samsung with significant labor violations, including underage workers and exploited student workers.

The price of progress

The same activists say it isn’t true that conditions for most Chinese workers have improved over the last few years. Apple, says Kevin Slaten, who works at China Labor Watch, is better than its rivals at communicating with the media, NGOs, suppliers and their workers, and he has witnessed its work to return child laborers to school. But China Labor Watch says conditions in the factories still have not improved much, and long hours and unpaid overtime dominate. Such conditions, already harsh for adult workers, are even worse for kids. Last year, a 15-year-old used a fake government ID to get work at a Pegatron factory building Apple’s latest iPhone. He died of pneumonia after working 12-hour days, six days a week, well over the legal hour limit for adult workers.

“[Child labor] is relatively low percentage of the labor violations happening in the supply chain, a relatively inexpensive thing to take care of,” Slaten says. “To pay a million workers unpaid overtime wages, it’s going to be a little chunk of their profit margin.”

Apple’s latest responsibility report says it found 71 facilities underpaying its workers in 2013, and forced them to repay $2.1 million in back wages.

“As far as where the multinational companies fit in this, they are not Chinese themselves, probably don’t have Chinese management, but they are taking advantage of the fact that labor enforcement in China has been lax,” Slaten says. “That there’s a governance gap doesn’t mean they can profit off it.”

But multinationals have long profited off loose labor standards in China and other emerging markets, much to the chagrin of manufacturing workers in the wealthy economies. The pressure such companies face after tragedies like the Foxconn suicides or last year’s collapse of a textile factory in Bangladesh means that they sometimes pay a price, but most of the time, the tolerance for systemic labor violations abroad suggests the price isn’t too high.

On the other hand, the work those companies create has helped lift millions in China out of poverty. “Trade is a good thing, a very good way to redistribute wealth, much more effective than aid,” Harrison says. And as people become more prosperous, she says, they’re demanding better conditions. “If you’re comparing like with like, conditions are better now [but] expectations are changing, and what workers want from their jobs is also changing. Their perceived quality of job is probably worse now than it used to be.”