Pabst Brewing Co., the 170-year-old brewery that makes Pabst Blue Ribbon—known as “PBR” to the mustachioed cognoscenti—is for sale, Reuters reported over the weekend. And the expectation is that the company will fetch as much as $1 billion.

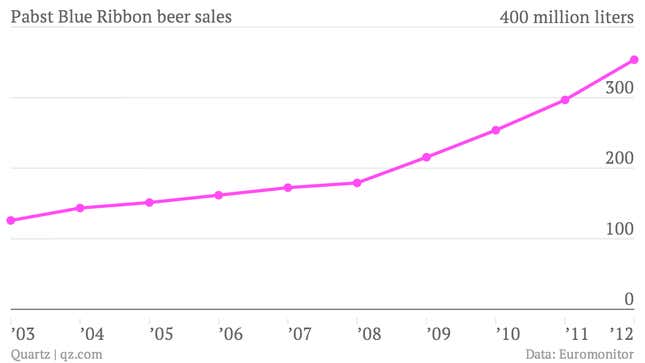

The past decade has been an incredible one for the brewery, and especially for its namesake beer. The pale, fizzy lager was popular in the 1970s, but lost its way in the 1980s and 1990s, hitting a low in 2001, when PBR sales dipped beneath a million barrels. But the 2000s have been all about highs for America’s favorite hipster beer, and PBR sales have grown in leaps and bounds.

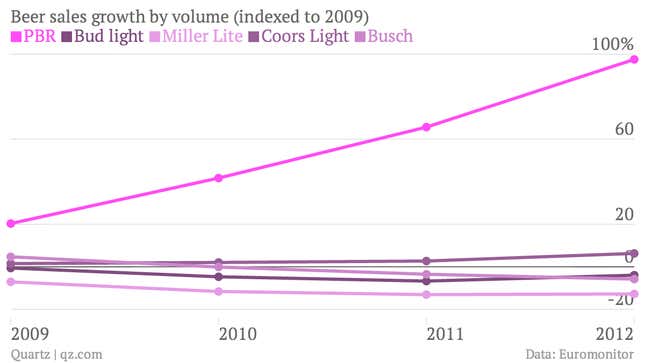

In 2009, sales jumped by 25%; in 2010, by nearly 18%; and in 2011, by roughly 14%, according to Beer Marketer’s Insights. While it still hasn’t approached the massive reach of Budweiser, PBR overtook Coors in volume sales back in 2006, and Sam Adams in 2010. Americans drank over 350 million liters (92 million gallons) of PBR in 2012, almost 200% more than they did in 2003, according to data from Euromonitor.

PBR’s rapid growth comes amidst a steady fall in American domestic beer consumption. The US is switching out beer for wine and other spirits, according to the market research company Mintel. The drop-off has been especially acute among young adults, and particularly unkind to lower-end brewers, like Miller and Budweiser—which both produce light lagers similar to PBR. The beer market, on the whole, is shifting toward craft brewers—which Pabst is decidedly not.

And yet PBR, which was founded in Milwaukee but is now based in Los Angeles, continues to enjoy some of its strongest growth years on record. It’s one of the only cheap beers that Americans are buying more of these days.

There was no brilliant marketing campaign to thank for PBR’s remarkable growth. In fact, its branding has been largely unintentional. PBR, as a product, isn’t all that different from its competition—cheap, low in alcohol, and watery. “It’s the drink of choice for people who like any evening of carousing to involve lots of visits to the bathroom,” the Washington Post jokes.

Even if you haven’t had the pleasure of tasting PBR, however, you’ve probably heard of it. That’s not because you’ve been bombarded with advertisements. Rather, it may be because you never were. After observing the beer’s unexpected popularity in Portland, Oregon back in 2001, the company concluded that people were buying the beer because it wasn’t aggressively being pitched to them. “Hipsters fetishize the lowbrow culture of the ’70s and ’80s,” Salon observed in 2008. “The hipster’s beer of choice is always going to be a cheap one.”

This new customer base felt that they were drinking PBR by their own volition, and Pabst didn’t step in to disabuse them of that notion. “The most interesting theory is that P.B.R.’s fan base grew not despite the lack of marketing support, but because of it,” the New York Times observed back in 2003.

And ever since, the company has stuck to the tactic of marketing itself by not marketing itself. While its competition pays millions for prime-time TV ad placements, PBR has opted for a more laid-back approach, which has worked marvelously. This strategy has also allowed certain unspectacular details—like the fact that Pabst doesn’t actually brew its own beer—to stay under the radar. And PBR isn’t even the cheapest of the cheap beers—in fact, it’s been blamed for driving up low-end beer prices. As CNN put it back in 2009, “PBR drinkers may want to look down-market, but they’re willing to spend a little bit extra to make sure no one mistakes them for the mainstream.”

With an upcoming billion-dollar buyout, it will be interesting to see whether PBR manages to hold onto its effortless indie cred.