China’s state media outlets are becoming increasingly sophisticated, mobilizing on social media networks and the web to quickly disseminate the details of a developing story—but only when the Communist Party lets them, of course. The gap between coverage of an approved news story and a censored one was on stark display this week, when two strikingly different violent news events unfolded.

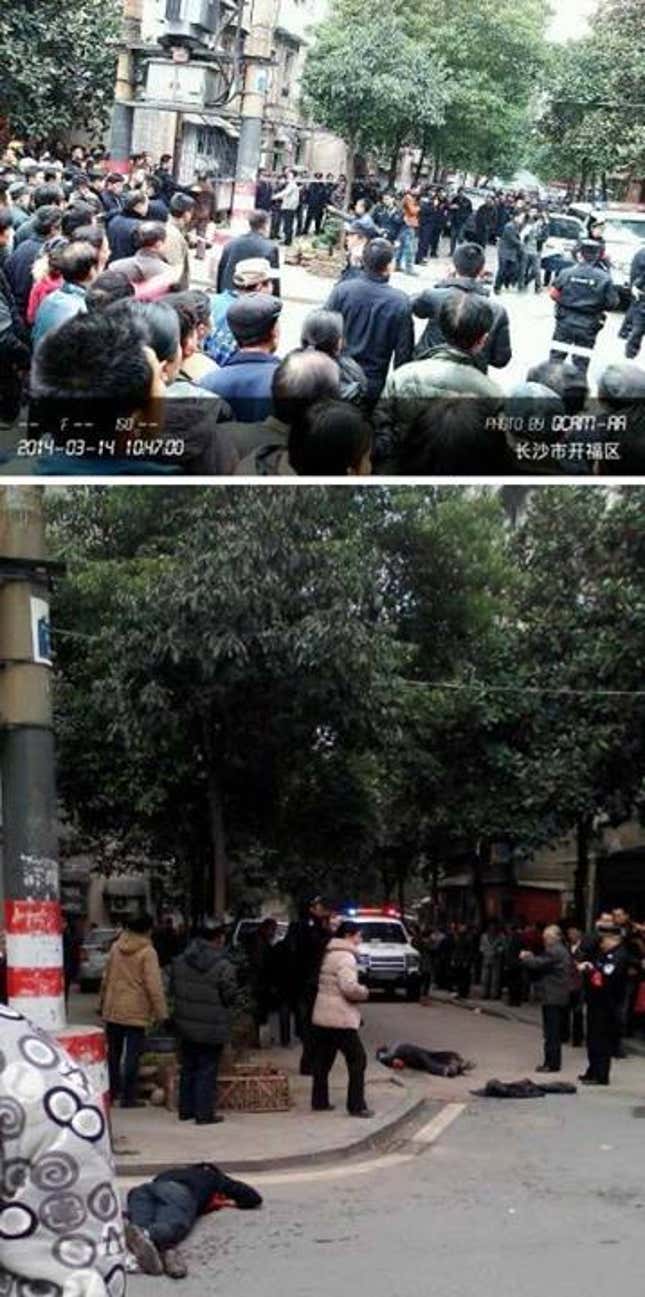

In the first incident, a group of five knife-wielding attackers killed at least four people in Changsha, the capital of the southern province of Hunan on Friday (March 14). The country’s state-owned media covered the attack with uncharacteristic swiftness and an eye toward a global audience, quickly posting images on Facebook and Twitter (both of which are blocked in China), as well as on their own English and Chinese language websites.

From People’s Daily Facebook page:

Xinhua, the state-run news wire, ran images of a man being arrested in connection with the attack, who did not look like he was Han Chinese, the country’s predominant ethnicity:

CCTV reported (link in Chinese) that the attack was triggered by a “dispute between street vendors and customers.” But the fact that it came less than two weeks after assailants with knives, said to be militant Uighur separatists, killed dozens in a southern China train station, sparked speculation that China had just been victim of another terrorist attack.

The topic was the second-most searched for on Sina Weibo (link in Chinese) on March 14, with thousands of users commenting about things like the “non-local” face of the attacker and espousing various theories. “This is definitely the work of pro Xinjiang independence terrorists,” wrote one user, but added “Most Xinjiang people are kind and friendly and we should not, just because of one organization, denounce this minority.”

Now consider another incident, with several times the death toll, which has been covered with a tiny fraction of the attention that the knife attack received.

Back on March 1, two tankers carrying the combustible liquid methanol collided inside a highway tunnel in Shanxi province, causing a massive explosion that destroyed over 40 vehicles.

Footage of the aftermath of the explosion shows blackened shells of cars and trucks being dragged from the tunnel. A firefighter described the grim scene:

The fog was so dense that the visibility was lower than three meters in the tunnel, which severely affected the velocity of water we could deliver. For a distance it usually takes ten minutes for the water to reach, it now took an hour. Part of the coating layer on the tunnel ceiling fell off due to the high temperature caused by the explosion.

The accident was briefly mentioned by Xinhua on March 2, with seven deaths and 10 injuries reported; other short updates raised the death toll to 16 over the next few days.

It wasn’t until March 13 that Xinhua reported a jump in deaths, to 31, with nine other people still missing. The explosion ignited coal that some of the vehicles were carrying, the report said. The 42 vehicles involved “were so badly burned that it has been difficult to confirm the number of deaths and conduct DNA identification of victims,” Xinhua said. The accident was made even worse by a fire hydrant that didn’t work and locked emergency escape shafts in the tunnel, Xinhua said.

Most state news reports only devoted a few paragraphs to the incident, and carried few photos of its horrific aftermath. A CCTV English-language segment about the accident carried a warning to international broadcasters looking to use the footage: “Restrictions: No access China mainland.” On Chinese social media, discussion of the incident is virtually nonexistent.

Government authorities issued instructions to state news outlets not to “hype” the Shanxi explosion story, according to China Digital Times, an anti-censorship media organization. “Related print and broadcast content must only use information from relevant government authorities and Xinhua wire copy,” the instructions state.

The incident’s high death toll, and the fact that eerily similar accidents have happened before, compounded by the lack of functioning safety equipment, suggest that there are real problems to be fixed in Shanxi, China’s coal-mining heartland. Most Chinese citizens, though, may never know that.