Almost a century ago, advertisements were so important to TV that we named an entire genre after them. Soap operas are only called soap operas because Procter & Gamble—the US personal care behemoth that makes, among many other products, bars of soap—produced a number of popular series in the 1950s and 1960s. Some shows, like Texaco Star Theater, even carried the name of their sponsors. Today, we’d call that a supercharged version of branded content.

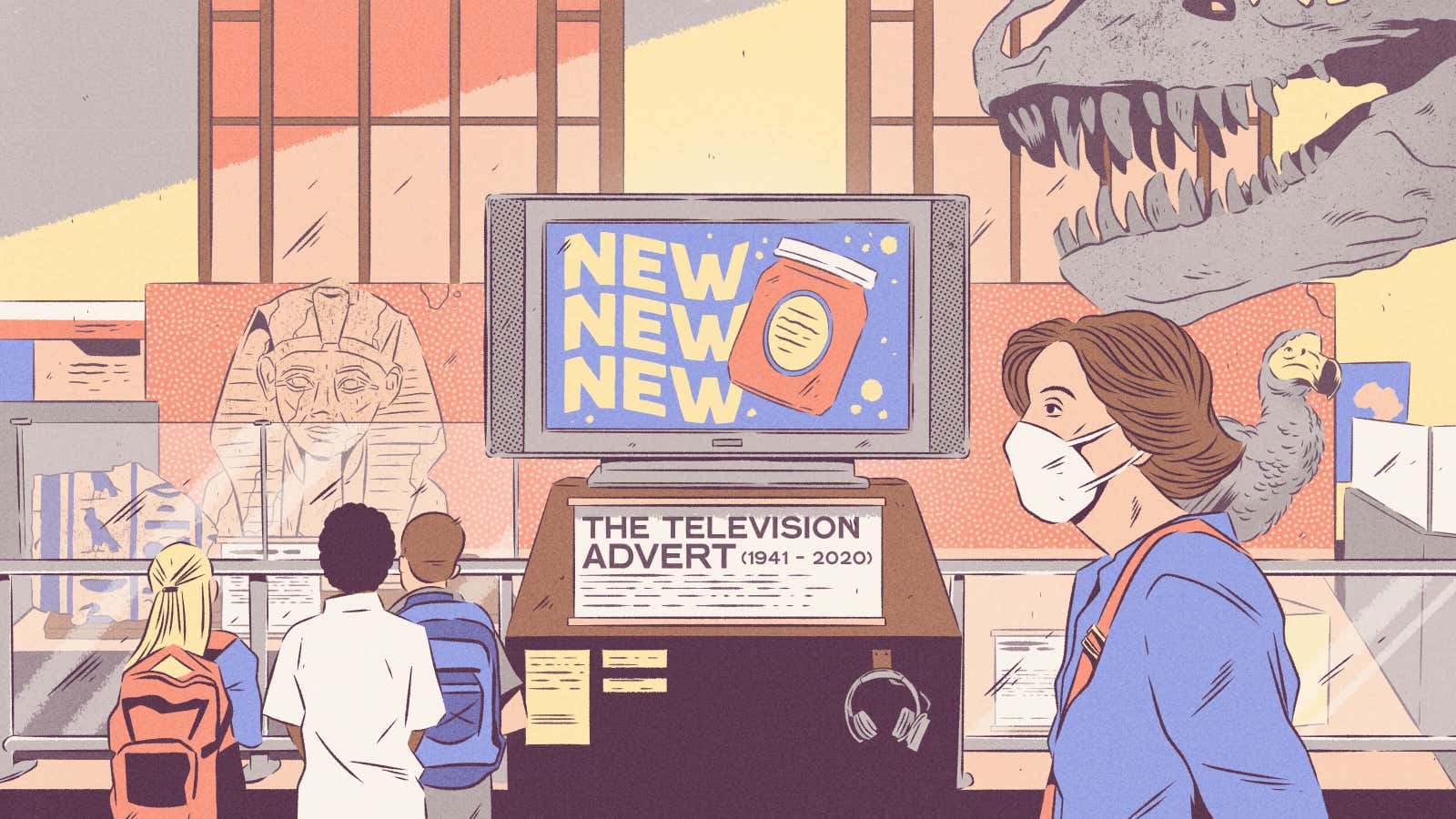

Brands don’t directly finance specific TV shows anymore, but their ads are still the lifeblood of the industry. Since the 1940s, advertisers have filled TV networks’ coffers in exchange for the opportunity to put their messages in front of huge audiences of potential consumers.

What those ads look like, how they are evaluated for effectiveness, and the way they’re bought and sold have stayed mostly the same since the medium’s inception. TV ratings have long served as the only way networks could tell advertisers how many and, broadly, what type of viewers were exposed to their ads. The 15- to 30-second commercial break format has remained just as immutable. While filmmaking and communications technology have fundamentally changed since the first half of the 20th century, the experience of watching content on TV hasn’t. It still looks a lot like it did for your parents and grandparents.

Historically, that’s because there weren’t as many other forms of media competing for your attention. But the fragmentation of consumers’ media diets is now profoundly altering how the TV ad business operates. It’s forced to reckon with the rise of ad-free streaming services like Netflix and web-based services like YouTube, as well as a surge in popularity of video games and other platforms. The last 20 years has also seen the rise of entirely new vehicles for advertising—web search and social media—that attract billions of eye balls. Consumers are everywhere and advertisers are struggling to figure out how best to reach them.

The industry’s transformation can be told through Saturday Night Live. “Live” is right in the name—it was conceived in 1975 as entertainment viewers would watch live on their TV sets. For a long time, that was true. Advertisers loved the simplicity of it, knowing exactly how they were connecting with viewers. But that’s not how we watch Saturday Night Live anymore.

Today, nearly 60% of SNL’s viewership comes from digital platforms, according to NBCUniversal data. And 60% of the viewing on those digital platforms is “short-form consumption”—meaning most fans aren’t watching the show straight through, but rather sketch by sketch. Not only is viewing spread out between TV and digital, but viewing within digital is also consumed in vastly different ways. That’s before you even consider the devices on which viewers are watching: About 70% still watch on televisions, but an increasing number are viewing on phones, tablets, and computers.

More options are great for the consumer. But it’s a nightmare for advertisers as they try to decide how much to spend on each medium, and how their messaging should change depending on the platform.

On top of existing fragmentation, there’s a global pandemic. All evidence suggests the coronavirus is accelerating a shift to digital consumption. And while TV ad revenues have been stable for decades, despite the myriad reasons for them to fall, the pandemic may be what pushes them over the edge.

The pandemic has crushed other industries, but advertising has been hit especially hard as consumer-facing companies pull back on their marketing. Ad spending in the US alone will decline 25% this year and won’t recover until at least 2023, the New York Times reported, citing data from the market research firm Forrester. Global ad spending is expected to drop about 9% this year. As a result, ad revenues at media companies are down across the board, including at conglomerates like Disney, WarnerMedia, and ViacomCBS. Even Google’s ad revenue will drop 5% this year—its first decline since 2008, according to eMarketer.

But of all types of advertising, TV has been disproportionately affected, due mostly to the postponement of live sports:

Media fragmentation and a pandemic-induced reduction in disposable incomes will force consumers to reassess which of their entertainment options are still worth paying for. Experts think that will even further accelerate a shift away from expensive TV cable bundles toward streaming and cheaper, ad-supported digital options.

For the big brands that rely on the $70 billion TV advertising industry to drive awareness, and the global media conglomerates that can’t afford to produce the content you watch without it, the next five years will be the most critical since TVs first entered living rooms. Companies that depend on TV ads will have to adapt to a rapidly changing media landscape or risk falling into irrelevance—and that means embracing a level of innovation they’ve never considered before.

Table of contents

Advertising dictionary | How we got here: The problem with TV ads | The data revolution | Future #1: Ads that are actually relevant | Future #2: Fewer ads | Future #3: Less annoying ads | The Great Convergence

Advertising dictionary

Before we dive in, here is some ad industry jargon you might see mentioned throughout this guide:

How we got here: The problems with TV ads

TV has serious issues, but it’s not disappearing overnight. Despite its shrinking and aging audience, advertisers still invest billions of dollars each year in the medium because they know, to some degree, TV ads can get consumers to buy stuff. Research from MarketShare in 2015 found that TV ads generate four times the amount of sales as digital ads at the same spending levels.

The Super Bowl is still watched by 100 million viewers each year. Regular season viewership of the National Football League has remained strong. TV still has the potential to reach lots of people.

“Television’s strength is doing these things at scale for the world’s largest marketers,” said Brian Wieser, the head of business intelligence at GroupM, the media buying division of the global ad giant WPP. “So long as the reach of ad-supported television is broader than anything else—even in a world of higher usage of digital media—television will still probably have the capacity to reach a wider range of people.”

Wieser likened linear TV—the industry term for the old fashioned ways of watching television—to a “melting iceberg.” It’s melting, all right, but it will take some time. That means networks and their advertising partners need to change the ad experience for consumers if they want it to remain a lucrative industry while there’s still ice left to melt.

People still hate ads

“Nobody openly says they love advertising,” said Dan Aversano, the head of ad innovation at WarnerMedia.

Survey after survey of global consumers show that they strongly dislike the advertising experience on most platforms, including television. And because of how much media we consume today, we’re all seeing a lot more commercials than we used to.

“The number of video ad messages a person is exposed to today versus 20 years ago is infinitely higher,” Aversano said. While that provides marketers with more opportunities than ever to reach consumers, it also risks making consumers even more resistant to absorbing those messages than they already were.

They’re too long

Not only do we see more ads today than ever before, but those ads also take up more of our time.

“There are certain programs on certain networks that are unwatchable because of the ad loads,” Aversano said. The data suggest that’s true. Quartz’s Dan Kopf looked at the average runtime of several popular US network TV shows and found they have gotten shorter over the last decade—because ad time has taken up a bigger part of every broadcast hour.

“Linear has become a bit of a runaway train in terms of escalating advertising time and clutter,” said Krishan Bhatia, the head of business operations and strategy for NBCUniversal ad sales. Bhatia and NBCUniversal are working on reducing that ad time and clutter (more on that later), but, for now, traditional TV still has a huge amount of ads.

They’re hard to measure

Virtually every advertiser Quartz spoke to cited the same issue with TV ads: They’re almost impossible to measure accurately enough to really know how effective they are.

Audience metrics are still primitive compared to the capabilities of digital platforms. Advertisers believe, generally speaking, that TV messaging works, since they tend to see a lift in sales when they run a TV campaign versus when they don’t. But they don’t know how to optimize those campaigns, nor do they know how much of their investments are being wasted on consumers who either aren’t interested in their brands or literally aren’t even in the room to see them. Nearly a third of TV commercials in the US air to empty living rooms.

“I don’t know necessarily what’s working and what’s not working because of the measurement limitations,” said Kari Marshall, the vice president of media at T-Mobile. According to the market research firm Kantar, T-Mobile was the fourth biggest spender on US TV advertising in the first half of 2020—dropping $135 million on the medium—behind Geico, Amazon, and the pharmaceutical giant AbbVie.

Fewer people are seeing them

The cord-cutting phenomenon of TV viewers ditching their expensive cable or satellite subscription packages, often in favor of streaming, is well-documented. In fact, the only thing that’s really still holding linear TV together is the existence of live sports, which remain the best—and only—platform on which advertisers can blast their messages out to a mass audience all at once.

With live sports on pause during the pandemic, advertisers saw how much worse things can still get for the industry. Every major TV provider is bleeding subscribers. AT&T, for instance, lost nearly a million TV subscribers in the second quarter of 2020 alone. Its overall subscriber base has eroded almost 30% over the last two years, from 24 million in 2018 to 17 million today.

In total, 20 million American homes have cut the cord since 2015. Another 27 million will do so over the next four years, according to research firm MoffettNathanson.

Companies are investing elsewhere

The median age of a live TV viewer in the US is nearly 60-years-old. So not only is TV reaching fewer viewers, but also a narrow group of them. Media companies are subsequently trying to reach consumers where they are, reorienting business plans to be digital first. TV is merely a component of a much bigger strategy. Only a few years ago, it was the core strategy.

No company is making that shift clearer than WarnerMedia. AT&T, which owns WarnerMedia, recently brought in the former head of the streaming service Hulu, Jason Kilar, to be CEO of WarnerMedia. If that wasn’t enough to make its intentions clear, WarnerMedia then fired a number of executives with backgrounds in legacy TV—repositioning the future of the company around the nascent streaming service, HBO Max. The service is currently ad-free like Netflix, but will introduce a cheaper ad-supported option sometime in 2021, Aversano confirmed.

“The push toward streaming isn’t a threat to our business. That’s the future of our business,” WarnerMedia’s Aversano said. “That’s the biggest opportunity for this company, not the biggest threat. We need to bridge to that future. But linear television isn’t just going to die. It’s going to be reinvented in the context of direct-to-consumer and streaming.”

Knowing legacy TV is on shaky ground, rather than try to save it, networks are more likely to reroute spending to streaming. Ad spending has followed this shift. About 60% of major TV advertisers surveyed by the investment bank UBS said they expect to shift ad dollars directly from TV to digital this year. Even before the pandemic, ad spending on TV was declining at a consistent rate:

“If networks continue to disinvest [in linear TV], at some point you get to a place where marketers just figure out a different type of media to work with,” Wieser said.

That different type of media is often streaming. But it’s also Facebook and Google. Those two companies make up almost 70% of all digital advertising.

The data revolution

Reinventing the TV ad experience starts with accessing—and harnessing—better data. TV networks want to know who you are and what you want in order to sell that information to advertisers. That’s a proposition that has existed on Google, Facebook, Amazon, and other digital platforms for years, but it’s still a relatively new concept for TV.

For a long time, the only data point TV advertisers had to work with was the content itself. “Content was the proxy for the audience,” Jeremy Helfand, head of ad platforms at Disney’s direct-to-consumer division, said. Eventually, once advertisers could (roughly) measure the size of an audience, that became a proxy for return on investment.

The truth is, no one—including the buyers and sellers of TV ads—knows much about the audience beyond sometimes age and general location. When TV was a more dominant medium, it acted as a megaphone, blasting out ads to a reliably large audience. Advertisers knew consumers were watching, and assumed some percentage of those viewers would hear their messages. Today, however, a large chunk of the consumers who might have once responded to a TV ad are now spread out all over the entertainment ecosystem.

That’s where data comes in. Because of geolocation, mobile, and app usage, credit-card data, and other forms of information about consumer behavior, networks, and their ad partners not only can get a better sense of what kind of person is watching ads, but also better connect business goals to ad exposure.

“We now have a lot of access to really compelling information and data about our consumers,” Aversano said. “We’re AT&T. We have a data relationship with your grandmother. Maybe your great-grandmother. We’ve literally had a billing relationship with hundreds of millions of consumers for over a hundred years.”

The availability of new data is changing every day. Earlier this month, Nielsen announced it would include “out-of-home viewing“—viewing of TV that occurs in public spaces like bars and offices—in its ratings reports. That’s especially important for tracking viewership of live events like sports, which are often aired in bars. It allows networks to charge advertisers higher premiums, because it’s likely to show larger viewerships. While advertisers won’t be thrilled about that, they’ll like having a more accurate picture of the number of consumers they’re actually reaching.

Data can also democratize advertising on TV. Typically, commercials on US, and global television are dominated by the world’s leading brands, as opposed to small- and medium-sized businesses. But better data mean small businesses will be able to tailor TV ad campaigns for their needs.

NBCUniversal recently rolled out CFlight, a proprietary measurement system that counts ad impressions across its linear TV and digital platforms to create an aggregate metric. In theory, that metric is much easier for advertisers to work with. Other companies are developing similar cross-platform measurement innovations, but they have yet to become widely adopted.

Part of the reason is the industry is too used to existing practices like Nielsen ratings, even though they don’t work very well. They’re consistent, and they’re universally understood. These new metrics, drawing from new pools of data, are scattered all over the marketplace.

“That’s why those old market principles have lasted as long as they have,” Aversano said. “There is consistency and standards that enables advertisers to transact tens of billions of dollars at a time. With all of this new data, if we don’t find some consistency and standards, we’re wasting each others’ time.”

Future #1: Ads will actually be relevant

Beyond more accurate measurement, the better data also enables “addressability,” or targeted TV ads. Imagine you and your next-door neighbor are watching the same live TV show at the same time, but during the first commercial break, you see an ad from Apple, and your neighbor gets an ad for Samsung. If you’re single, maybe you get an ad for a dating app, while your neighbor, who recently became a parent, gets ads for diapers.

Creepy, perhaps, but more relevant, and advertisers say that targeting can improve their sales. While the strength of TV is in its wide reach, advertisers still want the option of targeting a more specific type of viewer like they can on Facebook.

“It’s probably one of the biggest step changes in the traditional advertising ecosystem in the last 70 years,” Aversano said. “It changes everything.”

Though addressability is still in its testing phase, Aversano explained, investment by advertisers in addressable technology has increased each year to more than $3 billion in 2020. “The training wheels are off,” Aversano said. He expects 2021 to be the year addressable tech begins scaling, and 2022 the year it becomes “a real business.”

Every time you use your cable box or smart TV, those devices log information. That information can then be used to craft curated ad experiences viewers might tolerate more than what they currently get. Theoretically, it’s a win for everyone. But there are a number of roadblocks getting in the way of making addressable TV the standard.

First, it’s expensive. Advertisers have to pay a lot more than they’re used to for access to the type of data that’d allow them to curate ads for specific households.

Second, it inevitably leads to privacy concerns. Networks say they aren’t using information consumers haven’t already consented to providing, but once viewers start noticing the ads they see on TV are relevant—perhaps too relevant—they might get suspicious. Some ad tech companies involved in addressability space have already caught the attention of US regulators, and the scrutiny will only increase the more popular the method becomes.

Future #2: Fewer ads

Addressability makes ads more relevant, but it doesn’t make them any less present. Every TV executive Quartz spoke to acknowledged the volume of ads needs to be reduced on linear TV, which, for the most part, is still wedded to the traditional commercial breaks which on average take 15 minutes out of every hour of content.

Five years ago, half of US national TV ads were 15 seconds long, and the other half were 30 seconds, Bhatia said. Today, in an effort to cram more brands in, 70% of ads are 15 seconds. We’re seeing a lot more individual TV commercials, but the overall time of watching ads hasn’t decreased.

“That both deteriorates the user experience and also impacts marketing efficacy,” Bhatia said. “The more ads you see in a short amount of time, the less individual brands you’re going to retain. We’ve started to correct that.”

In 2018, NBCUniversal introduced “Prime Pods,” a standalone, 60-second pod of advertising for one sponsor that airs at the beginning or end of a primetime NBC show. There are no other brands’ commercials before or after it. It’s less ad time for consumers and more opportunity for the advertiser to stand out.

“We’ve been pushing aggressively to reduce the number of ad pods in programming,” Peter DeLuca, head of brand and advertising at T-Mobile, said. “Consumers just get overloaded.” On that note, DeLuca said T-Mobile was the sole sponsor of ABC’s commercial-free airing of Black Panther, a tribute to the late actor Chadwick Boseman. Viewers got to watch the movie without ads, while T-Mobile had a brief moment to stand out from the clutter.

Ad loads are much shorter on ad-supported streaming platforms like NBCUniversal’s Peacock. And they have to be. The major draw for consumers to services like Peacock is that they offer a more user-friendly ad experience than traditional TV. And in order to compete with completely ad-free services like Netflix, the ad experience can’t be unwieldy. Peacock has no more than five minutes of ads per every hour of TV you watch on the platform. An ad-supported version of WarnerMedia’s HBO Max, due out next year, will follow that lead, Aversano said.

Networks think they can make up for some of the expected loss of revenue from reducing ads by charging advertisers more for the ads they do run (and fewer ads might convince more viewers to pay for subscriptions). But there just isn’t enough evidence yet to say if that is true long term. Some think it’s a big ask.

“It’s very hard to unilaterally reduce your ad loads without planning on seeing a meaningfully reduced share of spending,” Wieser said. “You could try to increase your pricing, but good luck with that.”

Future #3: Less annoying ads

Okay. So there will be fewer commercials in the future. And the ones we do see will probably be more relevant. But they’ll still be “commercials,” right? Not always. Networks have finally realized the best way to disrupt TV advertising is to stop disrupting viewers. In the future, you could decide when and how you see a commercial break—not the network or advertiser.

NBCUniversal, Disney, and WarnerMedia are all coming up with new “ad formats,” or innovative types of video ads that don’t fall under the umbrella of the traditional 15- to 30-second interruptive commercial break.

One format all three companies are experimenting with is the “pause ad.” It’s simple: When you pause your video, a sponsored overlay will appear on your screen until you un-pause. It’s completely seamless and non-disruptive. Viewers literally have to take a physical action with their thumbs—in this case, clicking pause—in order to be exposed to an ad. It’s a form of consent.

Disney’s Helfand, who helped usher in the concept as head of ad platforms at Hulu, said the service’s users pause their videos a billion times per month. That’s a billion opportunities for ads that don’t interrupt the storytelling experience. Helfand added there’s a 68% increase in “ad recall” when viewers are exposed to a pause ad versus a traditional commercial. He claimed the viewer-first approach leads to tangibly improved return-on-investment results for advertisers.

“We are betting on the fact that an increasing amount of our business will come from those nontraditional formats,” Helfand said. Peacock is also running a pause ad, while WarnerMedia’s ad division, Xandr, is gambling on pause ads that play video as opposed to a static image.

Pause ads are just one new format. Another new form both Hulu and Peacock will use is the “binge ad,” which is an exclusive sponsorship that “rewards” viewers with an ad-free episode after they’ve watched three in a row. Both services are also developing more interactive forms of advertising, like shoppable QR codes that appear on the screen, and second-screen experiences that push offers to viewers’ phones when they opt for them.

Linear TV can introduce some of these new concepts as well, but because of the infrastructure, it’s much more limited. The traditional commercial break won’t just go away, but it will increasingly be supplemented with more innovative and less intrusive forms of advertising.

The Great Convergence

Ultimately, all of these fixes are founded on one shared belief among executives: The definition of TV has irrevocably changed. Advertisers can’t think of TV in linear and digital terms because, increasingly, consumers don’t. It’s all one industry. It’s all TV advertising.

“Linear and digital have been in separate silos, but we fundamentally believe that the expectation of where the industry goes is a point of convergence,” Helfand said. “You’ll be able to place an ad once with a company like Disney and be able to deliver that across all end points. That’s fundamentally important to the future of the industry.”

Next month, Disney will launch Disney Hulu XP, a system that allows advertisers to place a single buy across Disney’s linear and digital platforms, as well as Hulu. NBCUniversal launched a similar product earlier this year, OnePlatform, which promises advertisers access to all viewers across the company’s vast portfolio of channels and platforms. The idea is to digitize the TV buying and selling industry, and to get marketers to think of it a lot more holistically than they have for the past several decades.

As the advertising worlds fuse, the concept of television will change as well. “We won’t differentiate between what’s a linear TV experience or a digital experience,” Helfand said. “It’s all TV and that’s what we’ll call it.”