Raising prices is always risky for any business operating in a competitive market, but particularly for a disruptive challenger brand.

Just ask Netflix, which lost about 800,000 subscribers in late 2011 after a bungled attempt to raise the price of its service by about 60%. (There was a fierce backlash from consumers and a huge slide in its stock price, though Netflix has since recovered.)

For Amazon, which has built its entire business over the past two decades on aggressively undercutting the competition on price, it is an equally difficult proposition. That’s why the e-commerce behemoth’s recent decision to raise the cost of Amazon Prime memberships in the US by $20 to $99 a year is being watched so closely. The good news for the company is, early signs suggest it is going to get away with it.

Piper Jaffray analyst Gene Munster has analyzed consumer sentiment on Google and Twitter following the price hike and concludes it will result in “minimal” loss of subscribers. In the two days following the hike, Twitter references to ”Amazon Prime” spiked to 10,839, up from a 10-day average of 1,639, he found. But the wording of 80% of those tweets actually implied positive sentiment, up from 78% previously.

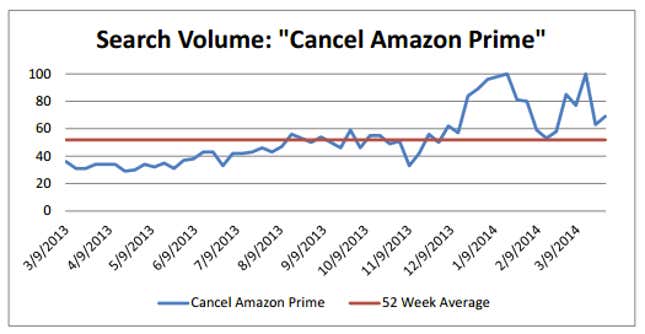

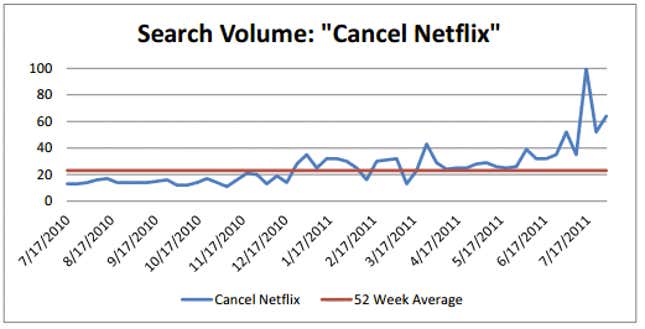

Meanwhile, Google Trends data showed a 193% spike in searches for “cancel Amazon prime” over the 52-week average.

And while that might seem like a lot, it’s nothing compared to the 433% spike observed in searches for “cancel Netflix” in 2011, Munster says.

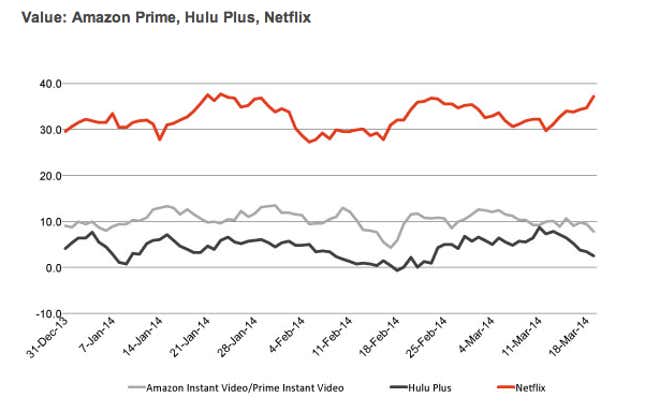

This dovetails with separate research by YouGov’s BrandIndex earlier this month, which found the Amazon Prime’s value perception has only moved slightly downward since the hike was announced (although consumers still see Netflix as a better value service, and Netflix’s value perception has gone up).

Amazon Prime offers consumers two-day shipping for almost anything they buy through the company, as well as a free online video and movie streaming service, and free one e-book rental per month. For anyone who buys anything on Amazon with reasonable frequency, it’s undeniably good value. (Cowan & Company estimates there are 23 million Prime subscribers, of which up to 85% buy something each month.)

Amazon first floated the Prime price increase on its January earnings call, saying the service could increase by as much as $40. That made the $20 hike seem small by comparison. The increase was also the first hike to the price of the service since it was launched in 2005. Of course, the incredible patience Wall Street has with Amazon—which, despite its enormous cash flows, still generates relatively meagre profits—allows it to do this.

But the lesson for other subscription-based businesses (like Netflix or Spotify) that might need to raise their prices in the future is clear: if you are going to hike fees, don’t do it often, and make it look like it could have been worse.