Nigeria has gained the crown as Africa’s largest economy, a status that could at last force its government to answer more for the country’s socioeconomic shortfalls than its new commercial success.

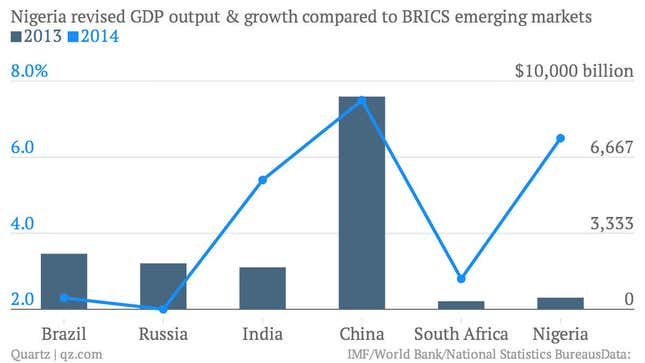

The West African nation surpassed longstanding business beacon South Africa over the weekend, after a government statistical revision nearly doubled its GDP output.

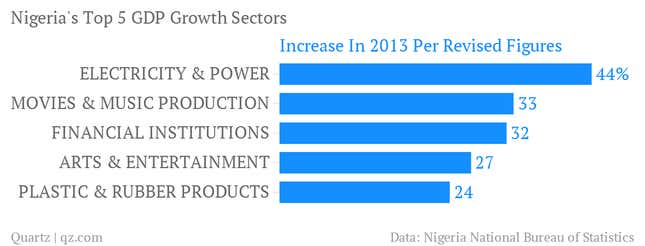

The rebased, IMF-endorsed figures place Nigeria’s GDP at $510 billion compared to South Africa’s $353 billion, and include previously unaccounted for sectors and commercial activity–demonstrating greater diversification to the country’s oil rich economy.

“This announcement brings prestige and with that responsibility. Nigeria is now the de facto economic representative for the entire continent,” says Nnamdi Chiekwu, founding partner of the Namdex Group, an Africa-focused private equity advisory firm. “The question is if the government will use that status to get its act together toward better opportunity for rank and file Nigerians. Otherwise, this number may not do anything except shed further light on the country’s challenges.”

Over the last 24 hours Nigerian government officials, such as finance minister Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala–a Harvard-trained economist and past candidate for World Bank president, have been pressed publicly to explain how the new economic title benefits average Nigerians. Traditional and social media alike are capturing frustration that the revised GDP figures have done little for upward mobility of the oil endowed country’s vast majority.

Okonjo-Iweala admits as much: “We’ve been growing in an unequal manner. We need better quality growth.” She also recognized the need for more government assistance to the country’s poor.

“Inequality has been rising so we need to build social safety nets meant to take care of those at the bottom of the ladder,” Okonjo-Iweala said, while stressing possible benefits of increased foreign investment and job growth through the nation’s new economic achievements.

Unfortunately for Nigeria, its challenges are more prominently known and often overshadow the country’s recent successes. In all of its potential, contemporary Nigeria undulates between points of progress and retrograde.

Days before the IMF endorsed the GDP restatement, World Bank president Jim Kim listed the country as one of the world’s extreme poor—a nod to the 60+% of its population eking by on less than a dollar a day.

As a small but growing Nigerian middle and entrepreneurial class demonstrates greater prosperity through increased consumer power, pockets of the country are in a state of low intensity conflict due to attacks by Northern militant group Boko Haram.

Nigeria has a burgeoning tech startup scene and record FDI, including several billion dollars in recent commitments by GE to upgrade power generation. Still, the latter underscores that only 40 million of the country’s 160 million people have access to electricity.

In 2013, Nigeria issued a historic $1 billion in Big Three-rated, JP Morgan-indexed government bonds to global investors, made possible by economic reforms credited to respected financial stewards like central bank governor and Time 100 honoree Lamido Sanusi. In February, president Goodluck Jonathan summarily suspended Sanusi amid the latter’s claims that $20 billion in revenue was missing from the state oil corporation, a charge sadly credible to most Nigerians given decades of documented and suspected state oil industry graft.

Then there’s the issue of unemployment. Conventional economic orthodox would predict an inverse relationship between growing GDP and the jobless rate, but youth unemployment in Nigeria has continued to rise to more than 30%.

“Tackling structural challenges will prove critical in making this GDP increase meaningful,” says Nigerian CEO and philanthropist Tony Elumelu. “Private sector investors and the government alike must now enhance our ability to compete globally as a top 10 economy, creating much-needed jobs in the process.”

Nigeria’s GDP revision leapfrogs the country over South Africa in total economic output–something surely to attract more attention from outside investors–but it will still take time to shore up its living standards and doing-business framework.

“Even with the new title, Nigeria will continue to trail South Africa over the next decades in terms of GDP per capita, basic infrastructure, and financial market sophistication,” says Samir Gadio, emerging markets strategist at Standard Bank.

Major shortcomings aside, Nigeria’s new economic crown could create the greatest impetus to date for public and private sector reform. While the moniker is currently more symbolic than directly significant to the country’s population, it does reflect Nigeria’s growing connectivity to global capital markets, foreign direct investment, and outside investments.

The government woke up to this new market check on politics interrupting macroeconomic policy during the Sanusi central bank ousting. The move (broadly viewed as highly political) sparked widening spreads on its new bonds, a drop in its stock market index, and tumbling currency valuation, forcing the government to launch a PR campaign to reassure markets. Even then, global rating agency Standard & Poors recently lowered Nigeria’s sovereign credit rating, citing “political infighting.”

Nigeria’s increased visibility as Africa’s No. 1 economy could shine the brightest global light yet on its old and new elite, most pressing problems, and public officials.

At the top, there’s already a new charitable Carnegie-Rockefeller-esque responsibility shaping up around some of its corporate moguls. This includes Aliko Dangote and Tony Elumelu. Each, previously highly successful in business, has publicly shifted notable resources toward foundations aimed at improving Nigerian opportunity and living standards. This is a relatively new phenomenon for Nigeria and Africa. Some of this philanthropic pressure is extending to outside corporate actors in Nigeria, like GE, which has already added significant corporate social responsibility efforts parallel to its recent Nigerian business activities.

And what could be even more impactful toward future economic dividends for Nigeria’s rank and file than new GDP stats themselves is the increased transparency and accountability created around their dissemination. The National Bureau of Statistics posted the full data online (government data has been historically difficult to obtain in Nigeria). And since the new numbers were officially released Nigerian public officials have been forced to answer to critical questions on income disparity and jobs to a national and global audience.

Though many standards have not yet increased parallel to Nigeria’s revised GDP, with its new economic status, the government can surely count on one new factor to rise as it inches toward 2015 elections: expectations on better governance by global investors and its people.