$20 billion and an ousted whistleblower threaten Nigeria’s fragile, carefully crafted success story

Nigeria’s soaring economy has met its match: old-style politics.

Nigeria’s soaring economy has met its match: old-style politics.

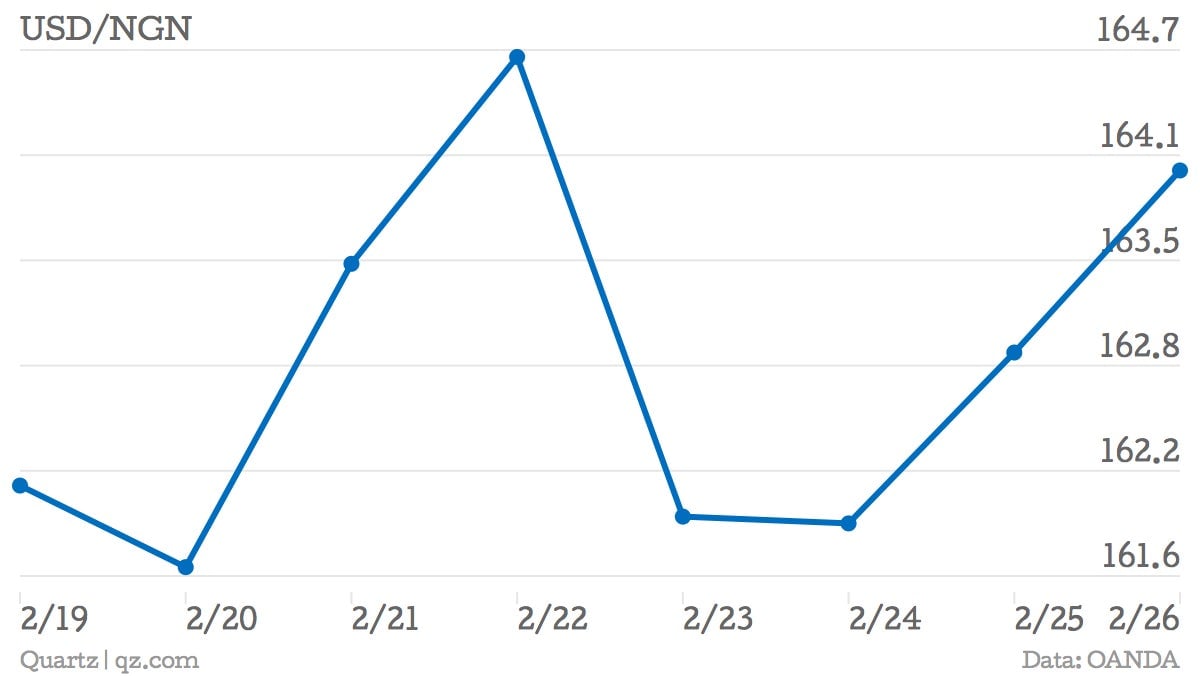

On Feb. 20, president Goodluck Jonathan suspended central bank governor Lamido Sanusi amid the latter’s claims that $20 billion in revenue was missing from the state oil corporation. The move sparked widening bond spreads and tumbling currency valuation in Africa’s most populous nation.

In a public statement, Jonathan said the central banker was relieved for “financial recklessness and misconduct”—a curious characterization for a man globally and generally regarded as a competent financial steward. In an interview with Quartz, Sanusi dismissed the allegations, pointing to his outing of oil graft as the actual reason for his discharge. “My sense is the government wanted me to stop a number of investigations and this was their way of getting me out of the way,” he says. Sanusi is pressing for an accounting of the missing $20 billion and on Feb. 26 filed suit in Nigeria’s High Court against Jonathan’s authority to suspend him.

The entire affair highlights the bumpy road ahead for a country jockeying to become Africa’s largest economy. It’s also a public relations debacle: Sanusi had become a leading figure for the country’s turnaround, gave a TEDx keynote, was named Central Banker of the Year in 2010 by The Banker magazine and a TIME 100 honoree in 2011.

The oil-endowed country, no stranger to allegations of cronyism and corruption, continues efforts to shake off perceptions of weak governance and national insecurity, largely related to northern militant movement Boko Haram. In early February, Jonathan implored foreign diplomats to do more to “convey the positive realities of the country to the world.”

Indeed, Jonathan likely did a disservice to his own plea, bringing even more attention to Sanusi’s credible oil fraud claims with the suspension. Yet Jonathan is right to be optimistic.

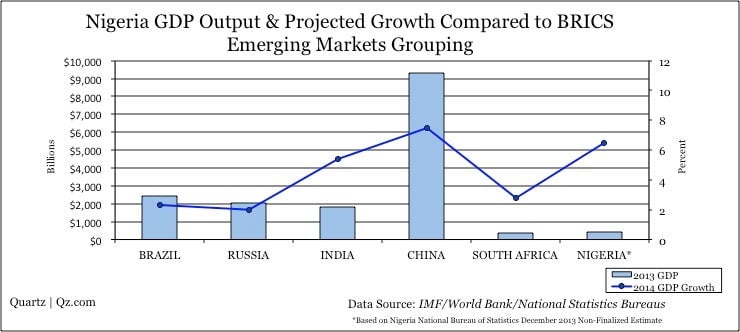

Nigeria is factoring prominently in Africa’s business driven transformation narrative. Soon to overtake South Africa as the continent’s largest economy (see BRICS chart comparison), its population is becoming a powerful new consumer demographic. Nigerian tourists are now the fifth largest spending nationality in the UK, as the newly rich buy up London’s luxury goods.

While oil is still central to its economy (95% of exports), Nigeria is showing signs of greater modernization, diversification, and global connectivity. The naira is the second most-traded African currency. Foreign investment is topping $5.5 billion. Silicon Valley is eyeing and funding the startup scene in Lagos.

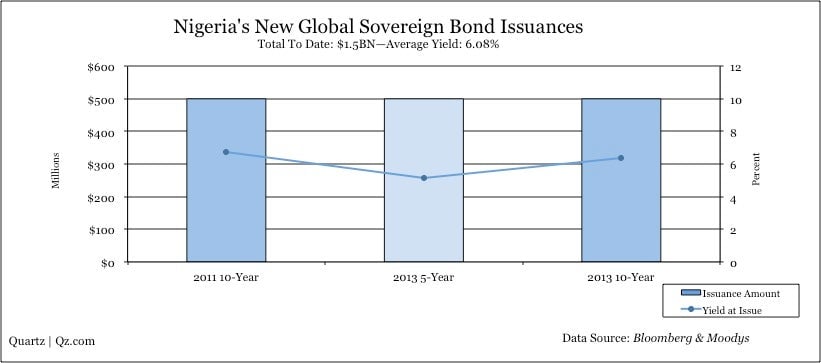

Then there is Nigeria’s important entry into global capital markets, from which it was once excluded from as an economic pariah. The country’s recent government eurobond issuances gained Big Three credit ratings and inclusion in JPMorgan’s benchmark EMBI index. Firms like Blackrock and PIMCO now hold Nigerian government debt listed on the same index as Brazil and Bulgaria.

Underscoring Sanusi’s influence, the success of Nigeria’s sovereign bond issuances, in particular, validates the macroeconomic gains shaped by economic policy makers like himself and current finance minister Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, a Harvard-trained economist and past candidate for World Bank president. The country has maintained relatively low debt-to-GDP (less than 20% compared to Spain’s 85%), largely met its Central Bank inflation targets, and runs a current account surplus.

Both Okonjo-Iweala and Sanusi have championed banking sector reform and greater transparency in the finances of Nigerian government institutions—initiatives that have been necessary to reach new economic benchmarks, like sovereign credit ratings from Moody’s, Fitch, and S&P.

And yet on Feb. 15, it appears Sanusi crossed an invisible line. Speaking before the senate, he provided detailed testimony that $20 billion was missing from Nigeria’s treasury at the hands of the state’s Nigerian National Petrol Corporation (NNPC).

Nigeria’s opaque oil-industrial complex has long had a reputation for making billion-dollar revenues vanish. Few with Sanusi’s access have pressed the issue as publicly as he did. Days later, he was suspended, his deputy named as acting central banker, and a top finance industry executive, Godwin Emefiele, announced as his successor. It seemed Jonathan had effectively politically exiled Sanusi, case closed.

Except it turns out Sanusi did not fade away quietly and that sweeping corruption under the carpet in more economically connected Nigeria rattles investors.

“The market did not take his [Sanusi’s] suspension very well for a number of reasons,” says Larry Seruma, managing principal of Africa-focused investment fund, Nile Capital Management.

“Sanusi has been a good governor. He’s been an inflation hawk. Current inflation is about 8%, the benchmark bank rate is about 12%, so you are getting a real rate of about 4%—pretty unusual in frontier markets. In his legacy he’s also done a number of things to stabilize Nigeria’s banking system.”

Foreign investor jitters immediately after the suspension led to a sell-off in Nigerian assets, a 3.2% one day drop in the naira, and 11-basis point yield spike on Nigeria’s 10-year eurobonds.

Not all the blame rests with the Sanusi shake-up, though. Nigeria has been contending with the same economic flu affecting many emerging markets that have been dependent on US Federal Reserve policy and reacting to its taper. “As the Fed tapers, the interest differential between the high-yielding assets in Nigeria and developed market assets has shrunk. Because of that you are seeing more investors pull out of Nigerian equities and fixed income,” said Seruma.

In the meantime, the Nigerian government has been doing all it can to reassure markets, issuing statements affirming continuity of monetary policy. One business day after the shake-up, Fitch walked a fine line in a Nigeria assessment. It reaffirmed the country’s BB-, Stable Outlook rating, referencing the CBN’s commitment to Sanusi like monetary policies, while acknowledging his concerns over “evidence of poor transparency and weak control in the oil sector.” The global rating agency went so far as to allude that the affair represented progress, given Sanusi was able to elevate allegations of state oil revenue theft as high as he did: “It is credit positive that these issues are increasingly in the public domain, and that the political will to address them in some quarters has increased.”

In an interview with Sahara Reporters shortly after his dismissal, Sanusi punched constitutional holes in the president’s authority to suspend him and pressed Jonathan to make good on an independent audit of the NNPC. He upped the ante on Wednesday, challenging his suspension by suing the president in Nigerian Federal High Court.

Contrary to claims from Jonathan supporters his moves are politically motivated, Sanusi confirmed to Quartz he has no ambitions toward next year’s elections or returning to his position.

“At this point I’ve made it clear, I am not interested in going back to the job…and I am not a politician,” he told Quartz. “I think we need to have the courts make a ruling as to whether the president has the power to suspend the central bank governor. It’s not about me, it’s about the institution [and] the next governor not finding himself in a position where he annoys the president and the president can write any kind of letter to suspend him.”

Pending the court’s ruling, the president’s dubious intervention casts a shadow over the bank’s monetary independence. “Sanusi’s suspension does raise credibility issues in terms of future CBN policy,” says Samir Gadio, emerging markets strategist at Standard Bank. “The next governor will find himself in a similar dilemma of driving independent monetary policy, while addressing the same inefficiency challenges coming from the fiscal side.”

As Sanusi awaits the March 12 hearing date for his suit against the president, the next public voice for his claims could become Finance Minister Okonjo-Iweala, who this week made public statements urging the forensic audit of the NNPC.

Still lingering is the question of the missing $20 billion—around 6% of Nigeria’s GDP. That level of public theft is staggering for any country, but especially one that still receives aid and is counting on the world to see it as a modern investment destination.

There’s also much more at stake than an economy—Jonathan and his government face elections in 2015. The Sanusi affair could seal transparency questions around Nigeria’s oil cabal as a pivotal election issue. That’s long overdue for a country aspiring to be Africa’s next superpower.