David Ebersman did well as CFO of Genentech, regularly making more than $4 million per year at the biotech firm. But his next career move brought far greater riches.

When Facebook was in the market for a finance chief with “public company experience,” it turned to Ebersman (pictured above.) The CFO joined the privately held social network in 2009, led it through its blockbuster $16 billion IPO three years later, and, last week, announced that he was leaving the company at the end of next month. During his five-year stint at Facebook, Ebersman will have made more than $100 million in salary, bonus, and stock awards.

Coding whizzes may be the rockstars of the tech world, but accountants are often more consistent earners. This is particularly true for companies looking to go public, of which there are many at the moment. Founders of fast-growing firms typically come from a technology or marketing background, and hire dedicated finance staff only after their companies reach a certain size. This is sometimes done grudgingly, as there can be resistance to the structure and discipline imposed by finance managers on a freewheeling startup.

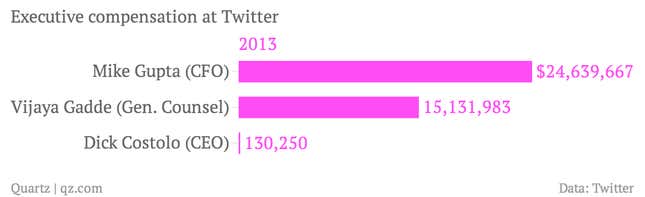

But if an IPO is on the horizon, structure and discipline is precisely what’s needed if a company hopes to get investors on board. And that’s why experienced financial hands can command huge rewards for their services. At Twitter, CFO Mike Gupta took home the largest pay package of any company executive in 2013, the year the company went public.

The same was true for Steve Cakebread at Pandora ahead of the streaming music firm’s 2011 IPO, which the company justified due to the “critical need to build the finance department in anticipation of a potential public offering.” There are many other examples of CFOs striking it rich during short stints before and after an IPO. (CEOs are generally wealthier than CFOs but, like Mark Zuckerberg at Facebook and Dick Costolo at Twitter, this derives from large initial stock holdings and isn’t reflected in relatively low pay from year to year.)

Been there, done that

What many of these finance chiefs often have in common is public-company experience, with previous IPO experience an especially hot commodity. Cakebread was at Salesforce.com when it listed, while Gupta helped manage Zynga’s IPO.

Iconoclasts and eccentrics may work well in some managerial and engineering roles, but when it comes to finance the private equity firms and venture capitalists that back tech firms prefer a “safe pair of hands,” says David Bloom, managing partner at FDU Group, a London-based recruiter that places financial managers at fast-growing firms. That means “people who have done it before,” he says. A CFO who’s managed a successful listing is often tapped to do several more.

If all goes to plan, there are few better-paying jobs for finance-savvy managers. The basic salary for a CFO at a pre-IPO company is generally around $150,000 to $200,000, says Bloom, with stock awards ranging from 0.5% to 3% of a company’s equity. It’s the stock that generates the financial windfall for CFOs if a listing goes well.

The work, while gruelling, is bread and butter for experienced finance executives. Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg recently told Bloomberg about how Ebersman, the finance chief, introduced some fairly basic financial processes to the company after he joined:

“I remember when he wanted to do a three-year budget,” she said. “We were like, we can do a three-year budget? And he did it. We’ve had very strong financial planning.”

Creative coders, brilliant marketers, and visionary leaders do not necessarily pick up the finer points of accounting, controlling, and reporting as they nurture their innovations and build out their companies. That’s why it takes a highly paid professional to introduce things like a three-year plan, something any run-of-the-mill widget maker can do, albeit with less pressure and a much lower profile.

Bloom says he has placed CFOs in finance departments that were “not fit for purpose,” even when the companies were on the cusp of an IPO. Introducing the systems and processes needed to go public can “really upset the apple cart in terms of culture,” he adds. Throw in the stress and urgency of the IPO process and these CFOs’ leadership skills will be tested as much as their accounting acumen. This is increasingly true for CFOs in general, not just at pre-IPO companies.

High risk, high reward

Although some companies insist on it, a lack of IPO expertise or experience at a listed company doesn’t necessarily rule out candidates for pre-IPO finance roles, according to Sarah Hunt, managing director of Equity FD, a London-based recruitment firm that specializes on placements at private equity-owned companies. What a candidate does need, however, is “the experience of going through some sort of transaction,” she says.

Managing an acquisition, divestment, bond issue, or other major deal gives finance managers experience juggling an external-facing transaction ”without taking their eyes off of the business,” Hunt says. CFOs who can make a company “look as good inside as it does outside” have the right skills to manage an IPO, even if they don’t have specific experience with a listing, she adds. Companies with board members who served at public companies or went through listings in the past are more willing to take on CFOs without IPO experience.

Hunt notes that companies also increasingly charge her with finding a finance chief for the long haul—”the CFO of the whole business and not just the listing process.” Financial rewards are often motivation enough to do a good job—these are CFOs we’re talking about, after all—but many boards and backers want the ”emotional commitment” of finance chiefs who pledge to stay on long after the listing, she says.

Many finance chiefs leave the companies they take public not long after their options vest. The adrenaline of the run-up to a high-profile listing can make the daily grind of life as a public company unappealing by comparison. The buzz, and the bonuses, that come from an IPO makes flitting from firm to firm irresistible.

For his part, Ebersman is returning to an unspecified job in the health-care industry after his short, spectacularly lucrative stint in social media, Facebook says. Along with Gupta at Twitter and other finance chiefs that have cashed in after IPOs, it’s enough to inspire people to put down the programming manuals and develop a newfound affinity for accounting.