Compared with the monster seas of the Pacific, Arctic waters are a picture of calm—whipping up, at their most violent, into lake-like chop. Or, at least, they were. New research shows that something is whipping up waves that reach five meters (16.4 feet).

“That’s a big wave—that’s a house-sized wave. And that has never been observed before in the Arctic,” says Jim Thomson, a physicist at the University of Washington who led the study.

So why is it happening now? ”As the ice retreats in the Arctic, which it is doing in a very remarkable way, we’re finding more and more waves,” says Thomson. “And we’re finding a very direct relationship between the height of the waves and the retreat of the ice.”

He’s talking about the sheet of ice that blankets the Arctic, which melts a bit in the summer and re-freezes throughout winter. Toward the end of the last century, the summer sun typically peeled it back at most 100 kilometers (62 miles) from the coast. Now the edge of the Arctic ice cover recedes thousands of kilometers.

Every summer, in other words, the planet gets a whole new ocean. And with a new ocean comes new waves, it turns out.

Wind is the major force creating waves. While it makes smaller waves locally, swells—those big, rolling waves that can rear up out of the sea in storms—come from much further away. That explains why, until recently, the Arctic had whitecaps, but no swells. But the polar icecap’s recent peel-back is opening up the huge spans of water needed to make waves big.

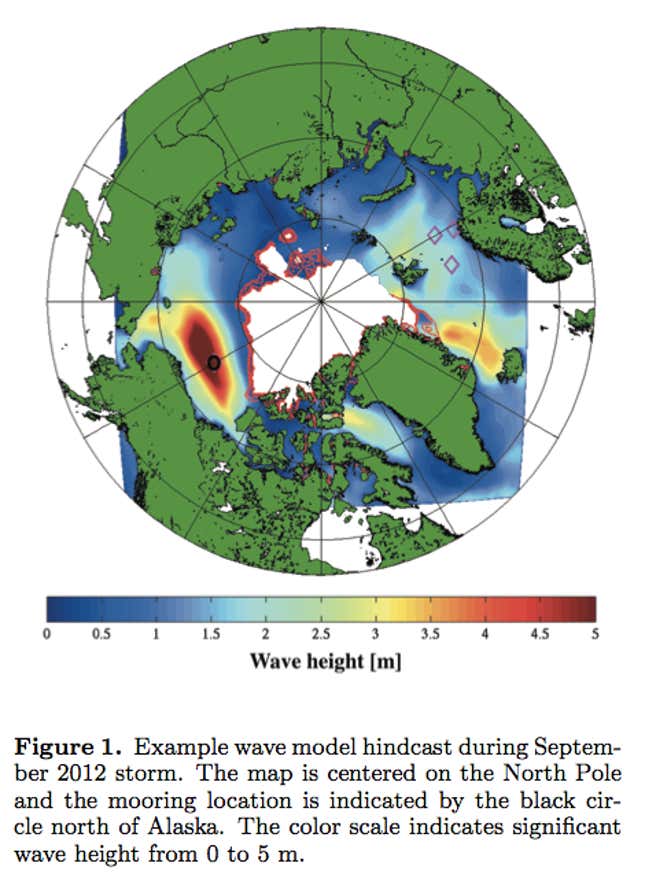

Take, for instance, the Beaufort Sea that skirts northern Alaska, which Thomson and his colleague Erick Rogers were researching. As late as April, that gap between the north pole and Alaska is completely blanketed in ice, and whereas it once retreated hundreds of kilometers each summer, now the ice disappears almost entirely. That’s why heavy winds in September 2012 kicked up these waves:

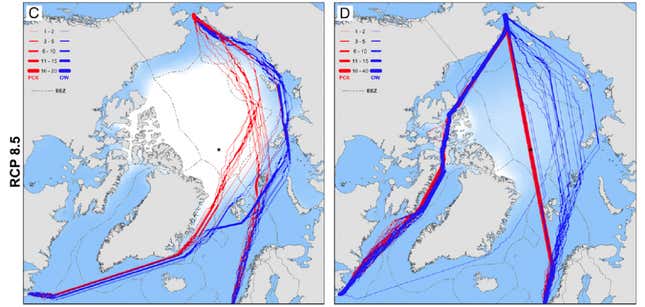

This is worrisome for a couple of reasons. First, there’s simply safety. The new Arctic waterway is exciting to commercial shipping companies, which see it offering a shorter trade route. China, for example, estimates that by 2020, up to $500 billion worth of its trade could transit through the new waterway.

The tradeoff, as Thomson and Rogers’ research suggests, is that more open sea means bigger waves—and more risk of danger. Between 2009 and 2013, the annual average of ships lost or severely damaged (pdf, p.3) in Arctic waters rose to 45, up from the 2002-7 average of seven ships, according to Allianz. And if the Arctic starts looking more like the rest of the ocean, that could get worse; storms caused three-quarters of all shipping losses last year, reports Allianz.

More ominous still is that the emergence of big swells is very likely accelerating the disappearance of Arctic ice. Swells carry much more energy. The force they deliver when they slam into the icecap breaks off floes, hastening the retreat—and creating ever-bigger swells.

On top of that, the huge amounts of foam created by big waves flushes more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere into the ocean, says Thomson. Though scientists aren’t clear how those gases get dissolved, that’s going to shake up Arctic chemistry in a way that is hard to anticipate.