Ships today are more likely to encounter an iceberg than the Titanic was

It’s common knowledge that a giant iceberg sank the Titanic. Less clear is why such a huge iceberg wandered so far south and into the famously “unsinkable” ship’s path. Though theories abound, the most popular of late is that a freak lunar positioning in early 1912 created a “once-in-many-lifetimes event” that allowed big chunks of ice to float farther.

It’s common knowledge that a giant iceberg sank the Titanic. Less clear is why such a huge iceberg wandered so far south and into the famously “unsinkable” ship’s path. Though theories abound, the most popular of late is that a freak lunar positioning in early 1912 created a “once-in-many-lifetimes event” that allowed big chunks of ice to float farther.

But apparently the presence of multi-million-ton icebergs in the North Atlantic isn’t really all that freakish, according to new research (pdf) into Atlantic iceberg sighting records by Grant Bigg and David Wilton of the University of Sheffield’s geography department. And various factors have increased the number of icebergs floating into shipping paths in recent decades.

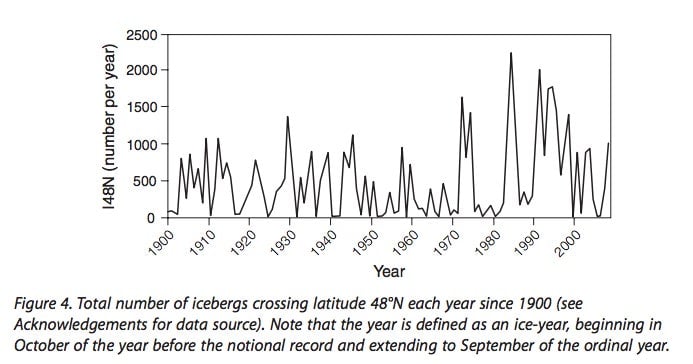

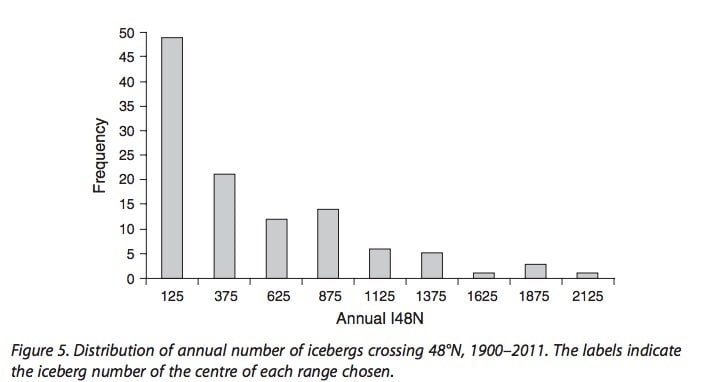

“We have seen that 1912 was a year of raised iceberg hazard, but not exceptionally so in the long term,” says Bigg. Since the year of the Titanic’s calamity, there have been 14 years with higher iceberg activity, he says. What’s alarming is that five of those years were in the 1990s, raising fears that as the climate warms, Titanic-esque navigational risks will climb.

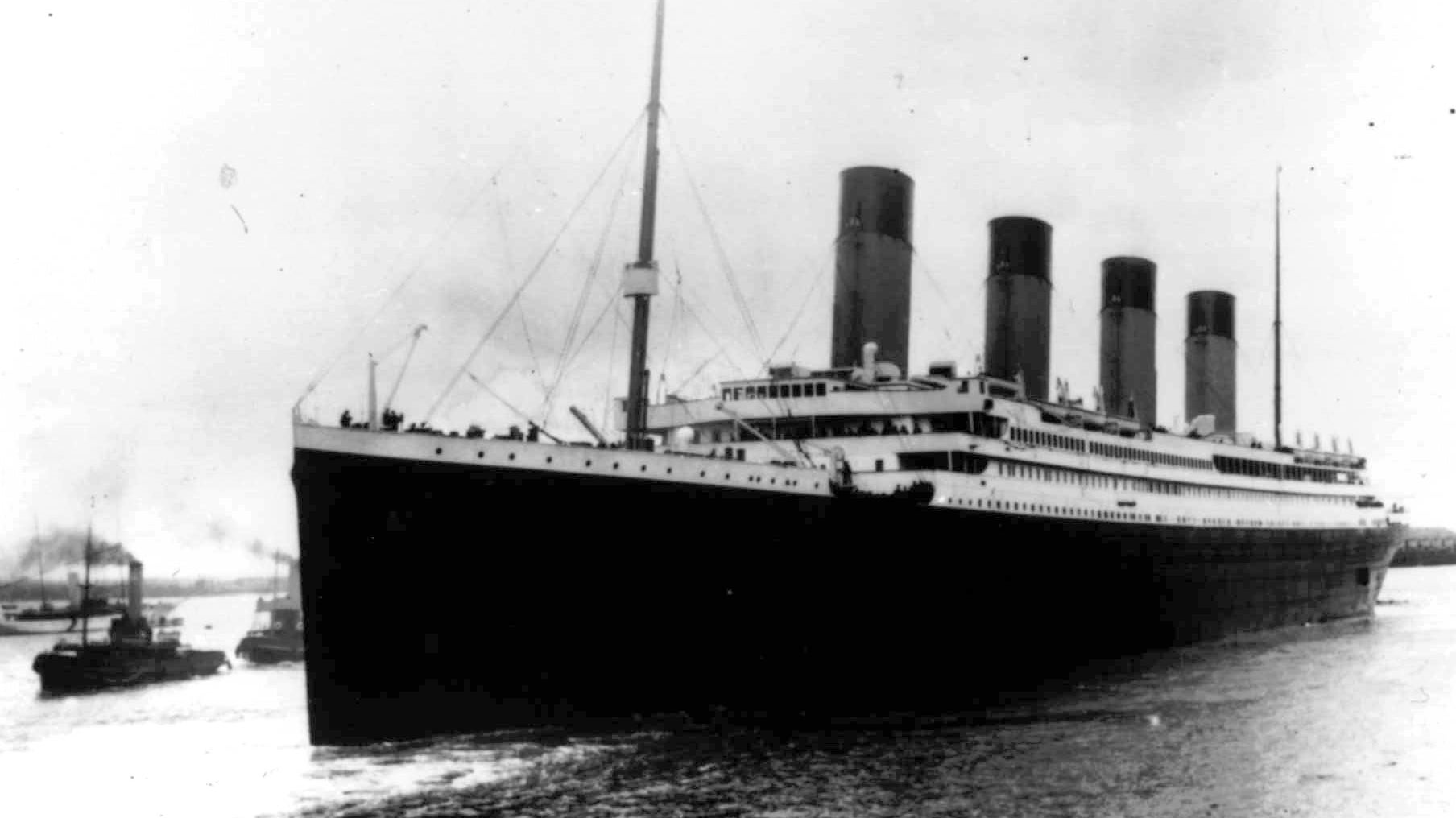

The iconically doomed ocean liner launched 102 years ago this month. By the time the crew spotted the 2-million-tonne (2.2-million-ton) iceberg, shortly before midnight on April 14, it was too late to avoid a collision. The ice punched through the cruise ship’s hull 100 meters (328 feet) below the surface, causing her to sink in two and a half hours, along with 1,517 people. Only 706 survived. The most we know about the notorious iceberg comes from two ships passing through the section of the North Atlantic where the Titanic had just sunk, whose crews noticed a streak of red paint along the iceberg’s base—probably from the Titanic’s hull—and snapped pictures.

Icebergs form over millennia, as layers of glacial snowfall become dense chunks of ice, forced seaward across the glacier’s bed by the weight of new snowfall. Meltwater and fresh snow lodged in ice sheet cracks loosen shards of ice, which Arctic tides eventually knock free—a process called “iceberg-calving.” The massive iceberg banged into the Titanic was one very old piece of ice, originating in snow that fell on a Greenland fjord around the time that King Tutankhamen ruled Egypt around 1,000 BCE, explains Wired. The warmer it gets, the more snow falls and more ice melts. In fact, a moderate 1908 winter in Greenland likely helped calve the iceberg that sank the Titanic a few years later, say Bigg and Wilton.

But while the 1,038 icebergs observed in the year 1912 was unusual, that doesn’t even put it in the 90th percentile in terms of iceberg activity in the North Atlantic since 1900. That’s largely thanks to a big uptick in iceberg-calving—which isn’t all that surprising when you factor in global warming:

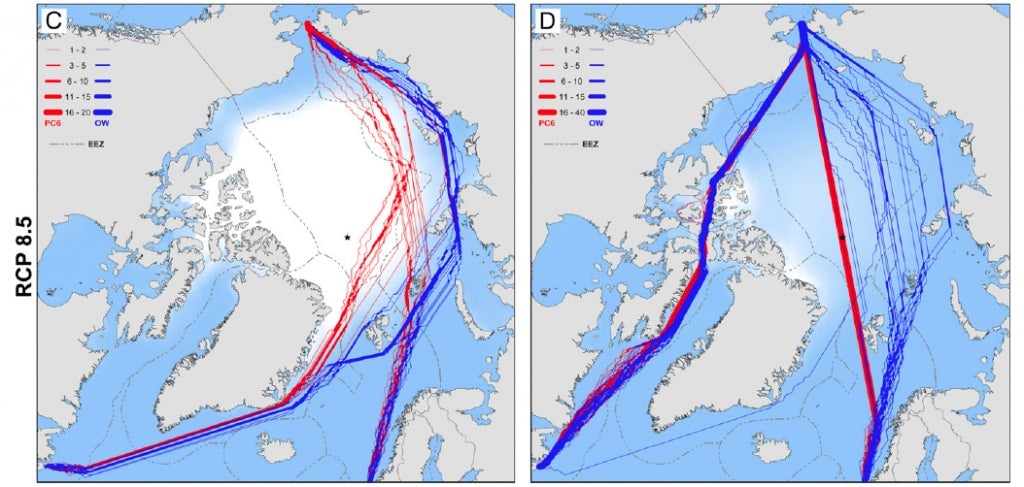

Climate change is also likely upping the navigational hazards icebergs pose (though ships today are better at avoiding collisions). In addition to the snowfall-and-melting double whammy, warm weather is causing a peel-back of sea ice that is making northern routes much more accessible, says Bigg. This has increased the number of ships in the path of drifting icebergs—and the risk of another “Convergence of the Twain.”