The future of digital music may hinge on Elvis

The music industry is in a strange place right now.

The music industry is in a strange place right now.

Music sales, both physical and digital, are in a death spiral, and the era of streaming-music platforms—be they financed by subscriptions or ads—is clearly upon us.

Apple may be paying $3.2 billion for Beats Electronics, at least in part for its streaming platform (although it’s been over a week and we’re still waiting for confirmation of that report). Twitter was in talks to buy internet music sharing service SoundCloud. Spotify could be considering an IPO.

Yet the traditional music business still seems uncomfortable with streaming. Pandora Media, by far the biggest streaming music company, had 76 million monthly active users at last count, and is now worth about $5 billion. But it’s been stuck in a quagmire of legal disputes since its 2011 IPO.

A few weeks ago we looked at how the music industry used questionable tactics to put pressure on Pandora to pay higher royalties to publishers and songwriters. Since then, the industry has found another stick to beat Pandora with. Last month, the Recording Industry Association of America and four record labels (Sony Music Entertainment, UMG Recordings, Warner Music Group, and ABKCO Music & Records) sued the company in the New York Supreme Court. They have accused it of “massive and continuing unauthorized commercial exploitation” of songs recorded before 1972.

The court submissions, obtained by Quartz, cite recordings made by the likes of Bob Dylan, The Beatles, Elvis Presley and David Bowie as examples of content that Pandora has used without paying for it:

Recordings include some of the most iconic music in the world, such as “Hey Jude,” “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction,” “Like a Rolling Stone,” “Good Vibrations,” “Heard it Through the Grapevine,” “Hound Dog,” “Johnny B. Goode,” and “Respect,” all of which are on Rolling Stone Magazine’s list of the “Greatest Songs of All Time.”

The same labels took similar legal action against satellite-radio firm Sirius XM in February, in the California courts. The Hollywood Reporter described that case as “a dispute that is four decades in the making”, which is “potentially worth hundreds of millions of dollars”.

Looking back

To understand this dispute, and why it matters, requires a bit of context. First, how the complex system of music royalties works.

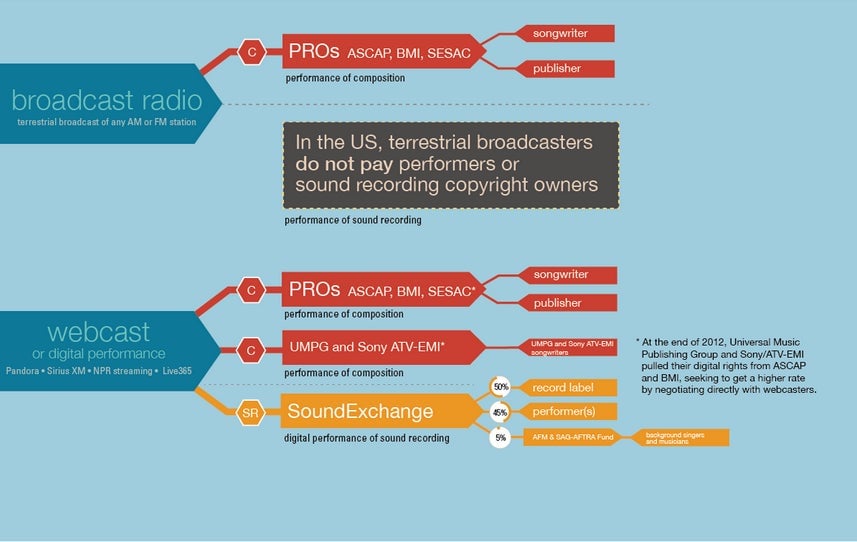

There are two forms of royalties paid on music. Composition royalties go to publishing companies and songwriters. Sound recording royalties go to record labels and performing artists.

Just to confuse things a bit more, publishing companies and record companies are often part of the same corporation (For example, Sony, Universal, and Warner all have recording and publishing arms), but individual songs don’t necessarily have the same ultimate corporate parent for composition and recording rights.

Compositions have been protected by US federal copyright laws since the 1800’s. Sound recordings only became protected in 1972, around the time that technology—notably, good-quality cassette tapes—made it possible to bootleg music at scale. But this change was never applied retroactively, so recordings made before 1972 aren’t protected.

That wasn’t an issue up until relatively recently, because there wasn’t much money in these old recordings. Terrestrial radio stations don’t pay royalties on sound recordings, from before 1972 or after; they only pay composition royalties (i.e., to publishers and songwriters).

But under a federal law passed in 1995, digital music services—such as Pandora and Spotify, as well as digital radio like Sirius XM—do pay sound recording royalties. In fact they’re Pandora Media’s single biggest cost. It paid out 53% of its revenue in royalties last year (49% went to sound recording royalties, and 4% on composition royalties). The company is estimated to be the single biggest payer of royalties to SoundExchange, an organization that distributes royalties to record labels and performers.

Recordings made before 1972, however, aren’t getting a piece of this digital action. And for older artists, and for record companies that own rights to lots of old recordings, that’s hard to stomach.

Federal vs state

Hence the labels’ lawsuits against Pandora and Sirius. These lawsuits are built on the claim that while pre-1972 recordings aren’t covered by US federal law, they are covered by state laws. That’s what the courts will have to decide. The Future of Music Coalition, a group that supports artists, has pointed out that there is a “patchwork” of state civil statutes, criminal laws, and common law that protects pre-1972 recordings, but as recently as 2011, the US Copyright Office found that “in general, state law does not appear to recognize a performance right in sound recordings.”

That 2011 report prompted Pandora, which used to pay sound recording royalties on pre-1972 songs, to stop doing so. Some other services do pay, though, including Spotify, which is reportedly part-owned by record labels and licenses songs directly from them, rather than through third parties like SoundExchange and ASCAP.

The record labels claim that Pandora has been violating “robust common law protection” for sound recordings made before 1972 in New York state. They claim the company copied thousands of old tracks to its servers without authorization and without paying for them, allowing it to profit “enormously” and gain an unfair advantage over other services that do. In short, the labels accuse Pandora off ripping off older artists. “These artists and their families rely heavily on the income they receive from the commercial exploitation of their performances,” the filing says. “However, they receive nothing from Pandora in return for its use of these performances.”

Dubious motives

Of course artists deserve to get paid. But the record labels’ show of concern for them is raising eyebrows. Because when opportunities have arisen to extend copyright protection to these same artists, the record companies have basically been against it.

Most recently in 2011, the RIAA and the American Association of Independent Music (or A2IM, which supports independent labels) told Congress that placing recordings from before 1972 under federal copyright could subject their members to “overwhelmingly burdensome legal, administrative and related problems, and accompanying costs.” It has been estimated that registering the songs for copyright would cost $35 per album, which may not sound like much but could add up for labels with large catalogs.

Casey Ray, from the Future of Music Coalition, has speculated that the labels’ opposition to extending copyright might be part of a strategy: to get services like Pandora to strike direct deals with them for content, as Spotify does, instead of have royalty rates set independently by the courts. He also points out that ”safe harbor” provisions—which protect online firms from being sued if users upload copyrighted content on to their systems—may not apply to non-copyrighted content, thus opening up online firms to more possible lawsuits.

Knock-on effects

Pandora is yet to comment publicly on the legal action. In its most recent quarterly earnings filing, it said it does not expect the case to “have a material adverse effect on our business.” But it acknowledged that if it is forced to negotiate individual licenses for every single song recorded before 1972, “the time, effort and cost… could be significant and could harm our business”. And if it can’t obtain licenses and has to remove the music from its service, that “could harm our ability to attract and retain users”.

For its part, in a submission last month to the Los Angeles Superior Court, viewed by Quartz, Sirius—which has older listeners than Pandora, and hence could face greater damages if it loses its case—has argued that there is are no state law precedents supporting the record labels’ position, and that their “hasty scramble for a legal foothold” is “meritless.” Sirius also argues that the labels’ claim that recordings made before 1972 are been covered by state laws is at odds with “their complete inaction” for decades to “enforce this supposedly well-established California right” despite “countless millions of performances of their pre-1972 recordings by all manner of broadcast and other users.”

The record labels aren’t seeking a specified amount in damages, although SoundExchange claims that unpaid royalties for pre-1972 recordings cost record labels “tens of millions in royalties in 2013 alone.” They argue that the “case presents a classic attempt by Pandora to reap where it has not sown.” Pandora, and its 76 million monthly users, will be hoping the court sees it otherwise.