Why the music industry is trying—and failing—to crush Pandora

This year marks the 15th anniversary of the launch of Napster, the file sharing service that disrupted the music business and conditioned a generation of consumers to expect to be able to listen to their favorite songs for free.

This year marks the 15th anniversary of the launch of Napster, the file sharing service that disrupted the music business and conditioned a generation of consumers to expect to be able to listen to their favorite songs for free.

Internet-based music platforms are legitimate businesses now, but tensions between the music establishment and new media remain as bitter as ever. They came to a head in the courts last month in a fascinating case between Pandora Media, now America’s biggest internet radio company, and the 100-year-old American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP.) It concerned the arcane issue of music publishing royalties, and uncovered some questionable behavior.

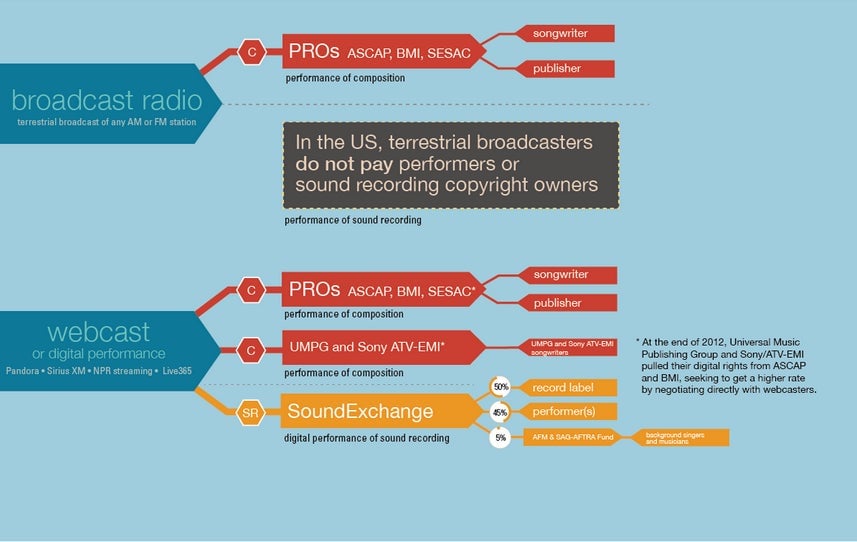

ASCAP is one of two main “publishing rights organizations” that act on behalf of songwriters to collect royalties from radio stations, movie studios, and technically speaking, anyone else (such as bars and restaurants) who plays music in public.

Pandora had been seeking to lower the amount it pays to publishers in royalties to be in line with that paid by terrestrial radio stations — 1.7% of gross annual revenue. Pandora’s argument was that its service is radio-like: Yes, you can personalize what you listen to, but you cannot play songs on demand, at your will, or offline. ASCAP had been seeking to increase rates to as high as 3% of Pandora’s gross revenue, citing the much higher rates paid by other digital services, such as Spotify. The court ended up ruling last month that the rate would stay unchanged at 1.85%.

But the tactics used by the music industry against Pandora were the really interesting part.

It’s complicated

Before we go any further, a quick explanation of how the mind-bendingly complex world of music royalties actually work is required.

Under a “consent decree” issued by the Justice Department in 1941, ASCAP and the other main publishing royalty organization, BMI, which together control about 90% of all commercially available recorded music, are obliged to grant blanket licenses to anyone (mainly radio stations) requesting them. When a fee can’t be agreed, a rate-setting court decides the percentage amount of royalties these license holders pay in exchange.

This arrangement makes it logistically possible for the radio business to exist—a station effectively only needs to deal with two companies, rather than millions of artists, composers, and publishers, to get access to a vast array of music. And songwriters don’t have to spend time worrying about negotiating or policing the licenses for their work.

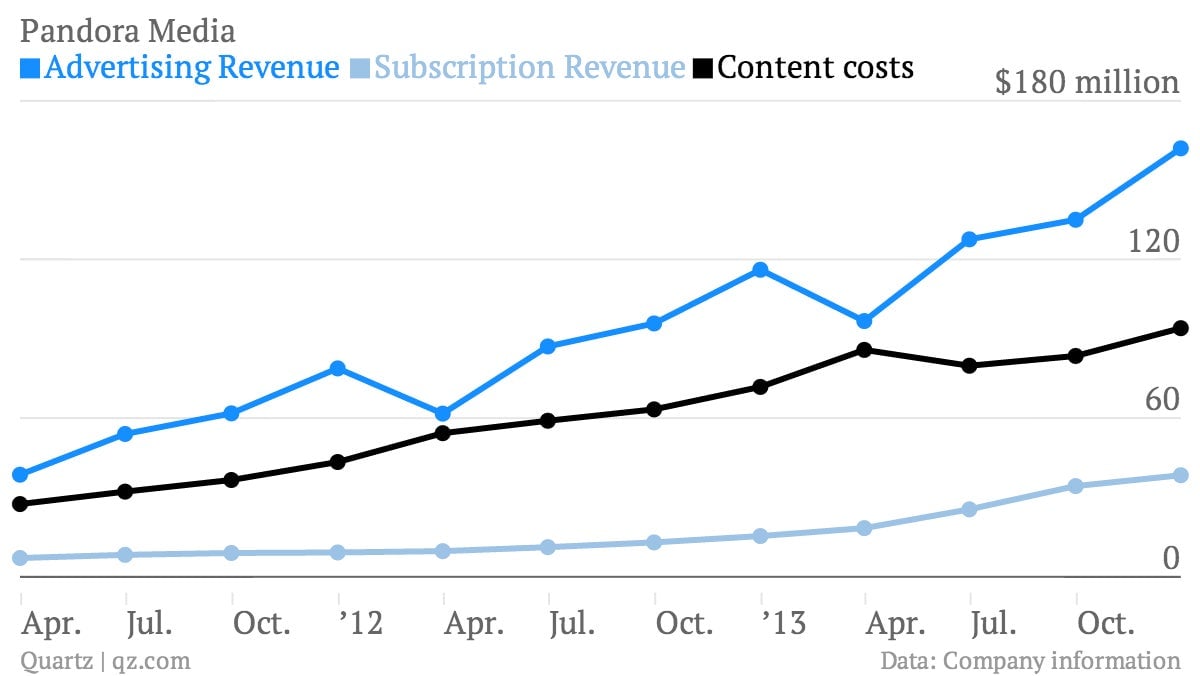

Unlike old-fashioned radio companies, internet-based services like Pandora are also required to pay separate performance royalties, which go to record companies, and then performing artists. In fact, this is Pandora’s single biggest cost. It paid out 49% of its revenue last year in performance royalties, compared to 4% in publishing royalties, which go to publishing companies, and eventually songwriters.

Just to confuse things a bit more, publishing companies and record companies are often part of the same corporation (For example, Sony, Universal, and Warner all have recording and publishing arms) but individual songs don’t necessarily have the same ultimate corporate parent for publishing and recording rights.

The astonishing rise of Pandora

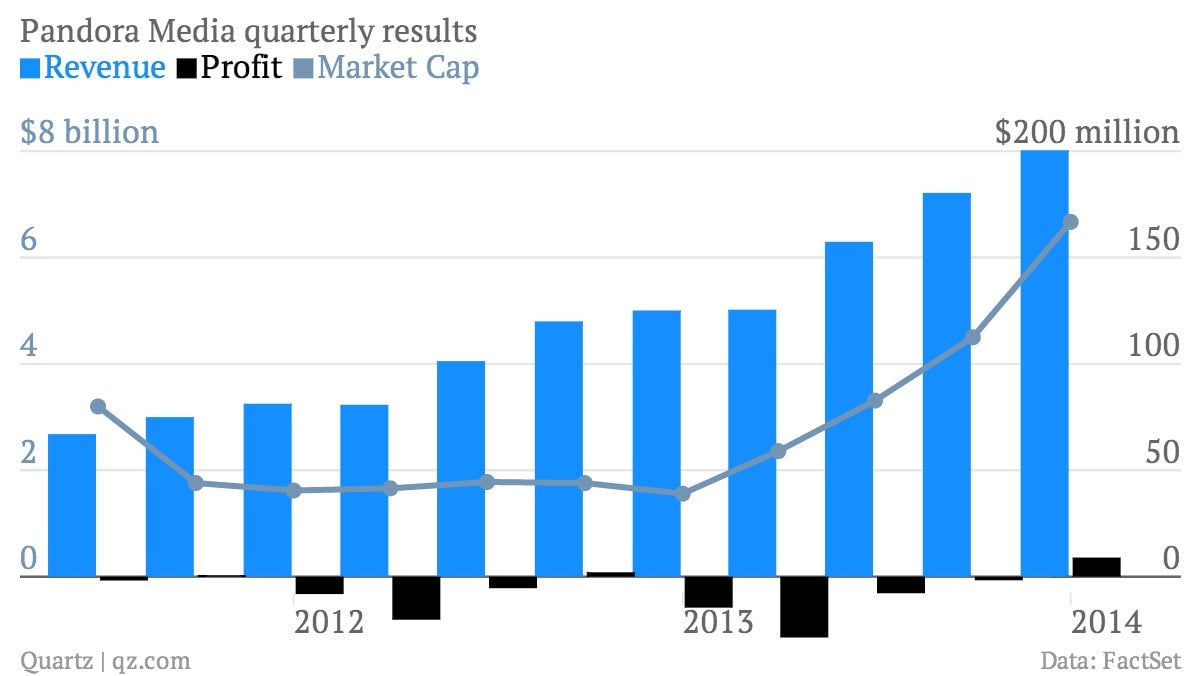

Pandora started its internet radio service in 2005. A five-year, experimental accord agreed with ASCAP that year was one of the factors that allowed it to do so. By 2011, when the company went public, it had amassed 80 million registered users, and was valued at about $2.5 billion.

Since then Pandora’s rise has been meteoric. At last count, the company had more than 200 million registered users (75 million of them were active, or logged in, last month) and accounted for 9% of all radio listening in the US.

The company last year generated about $638 million in revenue, paid out $342 million in royalties, and its market value had soared above $7 billion (the recent tech selloff has seen it fall back to about $5 billion.)

Pandora owes a considerable amount of its success to the “Music Genome Project.” For more than 10 years, a team of handpicked, professionally trained musicologists has been analyzing and classifying thousands of tracks using 450 distinct musical traits.

These are used to create a personalized radio experience that is clearly resonating (no pun intended) with listeners. When you set up a station on Pandora by typing in an artist or song, the idea goes, the only tracks that follow will be ones that you like. (Stations can be further tailored by pressing”thumbs up” or”thumbs down” buttons for songs that appear.)

Pandora describes the Genome Project as “the most sophisticated taxonomy of musical information ever collected” and its library now contains more than one million songs. But one piece of information about the songs in its library remains lacking: Who actually owns them. And for Pandora, this would soon prove to be a massive problem.

Taking care of business

The ownership structures behind recorded music are notoriously opaque. And the fine for playing a single song publicly without a license can be as high as $150,000. Which is why its so important to be have the relevant licenses with ASCAP (and the other publishing royalty organizations) in place.

Pandora’s experimental fee accord with ASCAP expired at the end of 2010. In October of that year, it applied for the same kind of blanket license used by radio stations. But ASCAP resisted. It was under pressure to get its members a better rate, and to close the gap with the royalties recording artists get (remember, Pandora pays out about 49% of its revenue in recording artist royalties).

Spotify, which is reportedly part owned by record companies (asked by Quartz to confirm, a spokesman declined to comment) pays 10.5% of its revenue in publishing royalties. Its service—which is almost, but not quite, music ownership—is different from Pandora’s in letting you play songs offline and on demand. Apple also recently agreed to pay 10% publishing royalties for its radio platform, but that business is very much ancillary to its electronic devices business.

In November 2012, Pandora commenced legal action to get the dispute with ASCAP resolved. And the evidence in the ensuing trial revealed the extraordinary pressure being placed on it. In her decision, US judge Denise Cote outlined (p. 97) “troubling coordination” between ASCAP and two of the world’s biggest publishing companies, Sony and Universal Media Publishing Group, against Pandora, that “implicates a core antitrust concern.”

Emails between Universal’s president Zach Horowitz and ASCAP’s CEO John LoFromento show that pressure had been placed on Pandora’s legal counsel not to represent the firm in the suit. Horowitz (p. 57) also urged LoFromento to “be strong,” describing Pandora as “scared.”

Pandora is now under intense pressure to settle with ASCAP. They have to put this behind them. You can really push Pandora and get a much better settlement as a result. They are reeling. They will pay more, a lot more than they originally intended, to do that.

In the months leading up to the case, Sony, which has the largest music catalog, withdrew its digital rights from ASCAP, intending to negotiate with Pandora directly in order to get a higher rate. If Pandora were unable to agree terms with Sony, it would be unable to play large swathes of its music library legally, or be liable for significant fines if it inadvertently did.

Mindful of this fact, Pandora in early November 2012 requested from both Sony and ASCAP a list of Sony tracks available for license so it could remove them from its service. According to the court documents, it reiterated the request throughout the month. Yet the information was not forthcoming, and the court papers indicate (p68) that this was part of a concerted strategy.

ASCAP personnel shared their amusement with each other over Sony’s decision to withhold the list from Pandora. In one email, [ASCAP executive Matthew] DeFilippis asked ASCAP’s counsel Richard Reimer “Why didn’t Sony provide the list to Pandora,” to which Reimer replied “Ask me tomorrow,” to which DeFilippis responded “Right. With drink in hand.”

According to the ruling (p66), Sony “quite deliberately” withheld this information to weaken Pandora’s hand in the negotiations. By December 18, with fewer than two weeks left in the year, Pandora agreed to a one-year deal with Sony at a rate that would see its total publishing royalty costs increase by 25% to 5% of its revenue.

A couple of months later, Universal also withdrew its digital rights from ASCAP, seeking a similar outcome. In negotiations with Pandora it sought a rate that would push Pandora’s overall publishing royalty costs up to 8%—double what they had been only months earlier. Despite a confidentiality agreement around its deal with Pandora, “Sony made sure that UMPG [Universal] learned all of the critical terms” of its agreement, the court papers show. It was a move that would give Universal an even stronger hand in negotiations.

“Sony and UMPG each exercised their considerable market power to extract supra-competitive prices,” Judge Cote wrote in her ruling (p. 97.)

Fight for your rights

ASCAP denies that it was involved in any “troubling,” coordinated behavior against Pandora. ”We respectfully and strongly disagree with the judge’s findings and conclusions on that issue,” an ASCAP spokesperson said in an emailed statement. Sony and Universal did not respond to requests for comment.

But it is clear that this fight is far from over. The publishing industry wants the consent decree abolished. In the music industry’s favor, it is difficult to think of any other form of media that must be sold to anyone requesting it.

“The Pandora rate court decision preserves a status quo that is unacceptable for songwriters and composers, thousands of whom depend on ASCAP royalties for their livelihoods,” ASCAP said. “As streaming has grown in popularity, so has the value of music on streaming services. Recent agreements negotiated without the artificial constraints of a consent decree make clear that the market rate for Internet radio is higher than 1.85%,”

Paul Fakler, a copyright lawyer and partner with New York based Arent Fox, who was not involved in the case, says that its highly unlikely that Judge Cote’s ruling will be overturned on appeal. “I think there is no question” of “troubling coordination” he says. ”I don’t know how one could come to any other conclusion.”

To get the 73-year-old consent decree overturned, the music industry needs to lobby the Justice Department directly, or less plausibly, get legislation through Congress. “It would be a disaster for the music industry” if the consent decree is abolished, Fakler explains, arguing that if there were no rate court, publishing companies could demand increases and licensees would have no choice but to agree. ”The entire digital music space would die, if suddenly you had no supervision over these licenses. Because if the consent decrees are gone, then they are gone for everyone,” he says.

The recent court decision means that publishing companies are either in ASCAP, or out. They can’t opt out of the organization only for digital rights. If they are out, it means they would need to use their own resources to complete the onerous task of collecting royalties from millions of bars, restaurants, and radio stations. It remains a possibility.

Nomura analyst Anthony Di Clemente told clients last month that the labels could still withdraw from ASCAP, which would leave Pandora faced with a “higher risk of increased costs, especially for higher-quality content.” But Fakler thinks it’s unlikely. “All of these music companies are firing people not hiring people. Even in the heyday they didn’t have enough staff” to police their licenses.

The song remains the same

The music establishment has another important ace up its sleeve in the battle against Pandora: high-profile music personalities.

Aerosmith lead singer Stephen Tyler has been another vocal critic.”If the laws continue going the way they are, [songwriters] will never be paid fairly for [their] own participation,” National Journal reported him as saying. Another songwriter claimed he had been paid just $16.89 after more than one million streams of a song.

Pandora has pointed out that it pays out a lot more out in royalties to record companies and publishers than artists and songwriters actually receive. But artist anger remains focused on Pandora rather than the labels and publishing companies, for now at least.

In coming weeks, Pandora is expected to launch a new platform that has been compared to Google Analytics or Chartbeat, and is designed to provide artists with greater transparency about how often, where and when their music being played. Meanwhile, a rate-setting case with BMI is underway, and just last week, record companies filed a fresh suit against the company over royalties for music made before 1972.

It is difficult to avoid the impression that the music business has it in for Pandora because it is an outsider. Other streaming music platforms are either owned by radio stations (iHeart Radio is owned by ClearChannel, Cumulus Media has a stake in Rdio) or the record labels themselves (Spotify, reportedly).

Yet of all the internet streaming products out there, Pandora’s product, built on the Music Genome Project, is the one that consumers have warmed to the most so far. It has about three times as many active listeners as Spotify does for its free, ad supported product.

Pandora already pays out more than half of its revenue in royalties. It’s just that most of this money (49% of its revenue) goes to record companies and recording artists, not publishers and songwriters. It’s almost the exact opposite situation to the paradigm that exists in terrestrial radio—where publishers get 1.7% of revenues and record companies get nothing. One argument is that the royalty situation should be sorted out between the publishing and recording companies, which, as we discussed earlier, are often divisions of the same parent corporations.

“We are disappointed to see a handful of powerful music companies fixate on a single innovator that already pays more than any other form of radio,” a Pandora spokesman says in an email. “Why single out Pandora when terrestrial broadcasters—with several times the combined revenue of Pandora—have never been required to pay performing artists a penny and offer songwriters a lower percentage of revenue?”

In any case, even without a rate increase, the more revenue Pandora makes (and through a push into into targeted, in-car advertising, the company is taking further steps to boost revenue), the more money songwriters and artists will receive in absolute terms.

Yet, while the company is growing fast, it is still losing money, and further increases to its royalty cost base will hardly help. The music industry could be trying to kill the goose that is about to finally lay it some golden eggs, as Pandora’s revenue and royalty payments rise with the surge in consumer streaming of music.

“The fact that 15, 20 years into the existence of digital music services, there has not been a single streaming service that has turned a profit on a cumulative or even an annual basis, the vast majority have gone out of businesses,” says Fakler. “Could it be that every single company was mismanaged, or couldn’t find a business model? The only explanation that’s rational is that the rates are too high.”