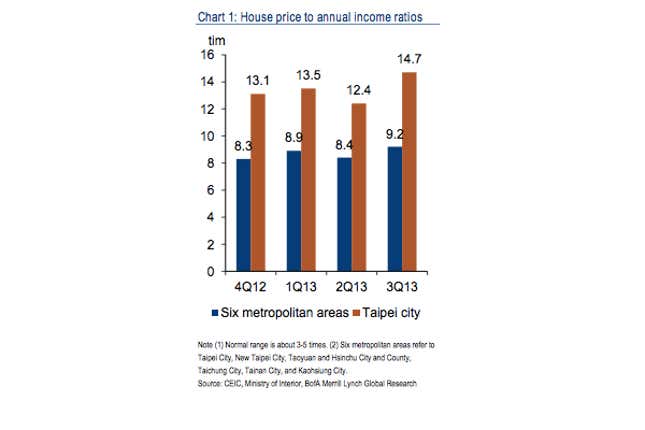

The city that now boasts the priciest housing in the planet isn’t London or New York—it’s Taipei. From Q4 2008 to Q1 2014, housing prices in Taiwan’s capital city leapt 91.6%, according to Bank of America Merrill Lynch. To buy a home, the average Taipei household must now save 15 years’ worth of wages—and that’s if they don’t plan to eat meanwhile. Here’s how Taipei’s prices compare to other urban areas in Taiwan:

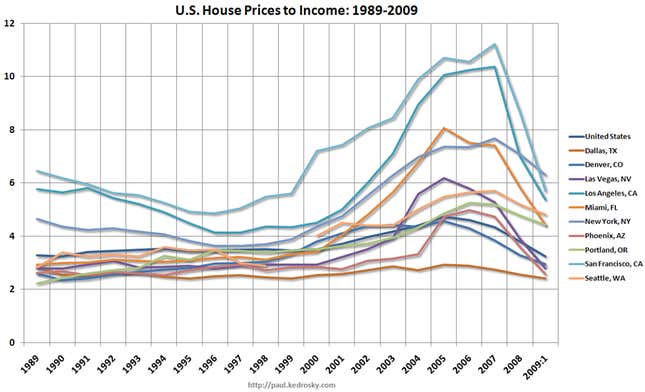

Even in the priciest cities at the peak of the US housing bubble, price-to-income ratios didn’t reach Taipei levels:

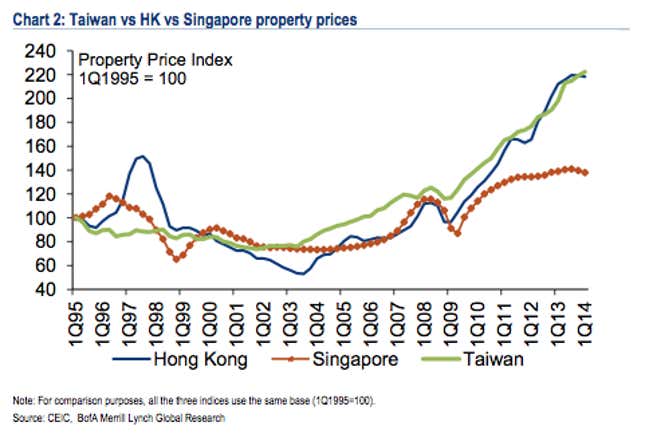

Taipei has two things to thank for its rocketing prices: quantitative easing by Western central banks (driving down yields on Western assets) and the deluge of bank loans out of its northern neighbor, mainland China. However, Taiwan’s regulators made things worse in 2009 by lowering taxes on real estate and gifting. Though the finance ministry countered that in 2011 with a luxury tax—15% on property sold within one year and 10% within two years—that’s done little to contain prices:

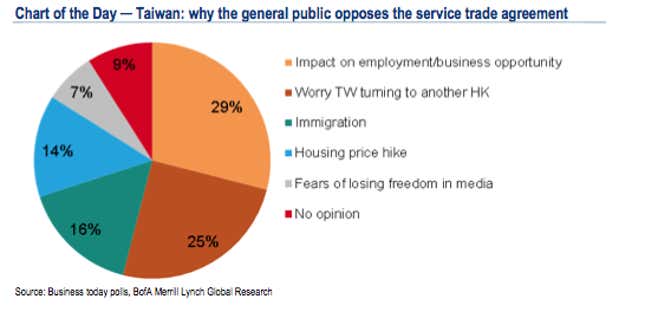

Younger Taipei residents are fed up—and as in other countries in the region, at least some of that rancor is directed at China. There was a series of huge protests in March and April over a proposed trade pact with the mainland that people feared would flood the housing market even more. (The protests stymied the trade deal.)

The government is raising taxes again in July, this time on non-owner-occupied properties. Taipei’s mayor and other government leaders hope the tax—as well as incentives for landlords who rent to poorer residents—will push prices down 30% within two years. In most places, this is would be called a housing market crash.

Planned or not, such a sharp drop would leave many of Taipei’s homeowners underwater. It could also hurt the economy more directly; real estate currently generates nearly 9% of Taiwan’s GDP.

The good news, for the economy at least, is that the tax will only apply to a property owner’s fourth unoccupied holding, says BofA/Merrill Lynch. Another reason its impact will likely be minimal is that it taxes the government’s property value assessment, which tends to be much lower than the market value.

Effective or not, this focus on combating speculation alone ignores some of the problem’s deeper roots. Taipei needs to replace old buildings with new ones, but the pace of this urban renewal is slow. The rapid clip of the capital’s aging is driving up prices too; seniors tend to have the means to demand fancier—more expensive—properties, discouraging the development of apartments that might be in the reach of younger people.

With all that in mind, BofA/Merrill Lynch argues that a better approach for policymakers is to focus on driving up wages, which have stagnated in recent years. The trend is even worse for younger workers. In 1999, college graduates commanded an average NT$28,551 starting monthly salary (US$946.83 in current terms); last year, it was NT$26,061.