Time magazine is coming full circle. This Friday (June 6) its publisher, Time Inc, is expected to begin trading on the New York Stock Exchange as a standalone company, returning to the status it held for more than a quarter century between 1964 and 1990. It is the latest in a long list of corporate transactions that the owner of one of America’s first weekly magazines has been involved in since it was founded in the 1920s.

Those transactions also reflect some of the epoch-defining trends in both the media business (the rise and fall of print, the internet) and the financial industry (M&A fever, the dot-com boom and bust, conglomerate empire building, and subsequent value-driven breakups) since then. Friday’s return also means that, for at least the next few months, there will be three Time-related companies trading in the US equity markets, (no doubt leading to great confusion for casual observers of the stock market):

- Time Inc: a publisher of magazine titles including Time, Fortune, and Sports Illustrated.

- Time Warner: a media conglomerate that owns, among other businesses, HBO and CNN.

- Time Warner Cable: America’s second biggest cable TV operator, which is in the process of being taken over by Comcast.

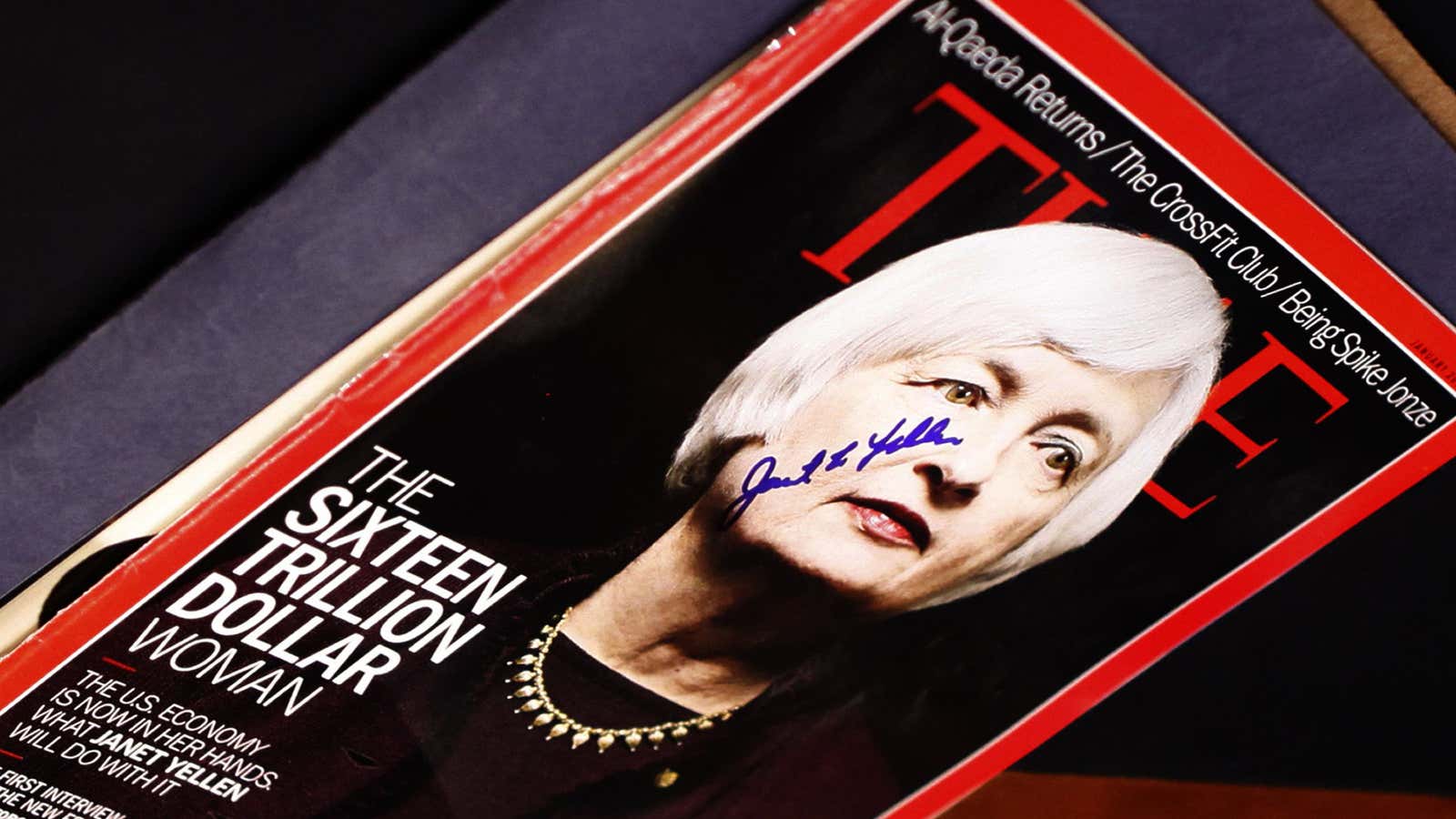

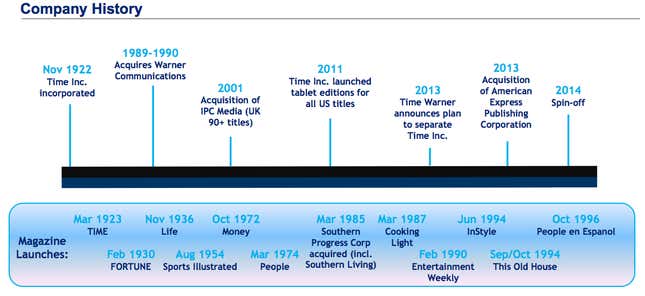

Just a few years ago these, these businesses were all part of the same corporate empire, one of the biggest the media world has ever seen. This chart from Morgan Stanley gives a sense for how it emerged and unravelled.

But it’s actually far more complicated than that.

Springing to Life

Time Inc was founded in 1922 by Henry Luce, a Chinese-born missionary’s son, and his high school and Yale classmate Briton Hadden. The magazine started publishing in 1923; For 1927, the aviator Charles Lindbergh was named as its first Man (now Person) of the Year, giving birth to what would arguably become its most recognizable feature. In 1936, Luce bought Life Magazine and turned that little known title into a publication focused on photojournalism. Business boomed, the company’s legendary midtown Manhattan headquarters, the Time-Life Building, opened in 1959, and in 1964, Time Inc commenced trading on the New York Stock exchange (it had previously traded on the over-the-counter market).

When Luce died in 1967, his Time Inc. stock was reportedly worth $109 million. He had built what the New York Times described as “the most important publishing empire of the middle twentieth century”. The empire building continued after his passing. In the 1970s, Time was experimenting with media businesses beyond magazines and agreed to financially back a young entrepreneur, Chuck Dolan, who was developing a pay-TV service delivered over cable wires. In 1972, Dolan and Time launched Home Box Office in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. In 1975, HBO broadcast the”Thrilla in Manilla”, a boxing fight between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier, across the US via satellite. Today, HBO is a premium channel with more than 100 million global subscribers and nearly $5 billion in annual revenue.

Big Time

The 1980s were years of notorious corporate excess. So it’s hardly surprising that in that era, Time Inc agreed to merge with Warner Communications to create what was then the world’s largest media conglomerate, with a market value of $15 billion and annual revenue of $10 billion. Warner owned one of Hollywood’s historic film studios, Warner Bros, as well as a record label and some cable TV systems, and the deal positioned the new company to take on against increasingly integrated European and Japanese rivals. “This is not a transaction done for the purposes of 1989, or even the nineteen-nineties,” Richard Munro, Time’s chairman said at the time (as the New Yorker’s John Cassidy recalled last year). “It is for us to be positioned for the next century.”

In 1995, Time bought out Turner Broadcasting System, the owner of CNN, which was controlled by the billionaire Ted Turner. The $7.5 billion deal was also transformative, catapulting Time Warner above Disney in terms of annual revenue, the New York Times reported. But those transactions were small-time compared with what came next.

In 2000, right at the peak of the tech bubble, Time agreed to merge with internet company AOL in a deal worth an astonishing $350 billion. It remains the biggest M&A deal in history, and inarguably one of the worst. At the time, proponents hailed the combination of new media and old as one that could dominate the internet for years to come. But it was ultimately a disaster that cost billions of dollars in shareholder value and resulted in Time Warner being embroiled in regulatory investigations into AOL’s accounting policies.

Ironically, Time Warner CEO Gerry Levin’s prediction that the internet would “unleash immense possibilities for economic growth, human understanding and creative expression,” proved accurate. It’s just that other companies like Google and Facebook, not AOL-Time Warner, were the ones that managed to exploit it.

Breaking up

Just two years after the disastrous transaction was consummated, Time Warner sought to distance itself from the internet service provider, ditching AOL from its official name and even reverting to its earlier stock trading symbol (TWX, which it retains to this day). In 2008, it decided to spin off Time Warner Cable, which had basically become an infrastructure business (owning pipes that deliver cable TV and broadband) with very different capital needs. The spin-off deal netted Time Warner $9.25 billion. In 2009, Time Warner decided to wash its hands of AOL altogether, spinning off the business into a separate entity. Today, AOL owns websites like the Huffington Post, TechCrunch and Endagaget, but it still makes most of its money out of dialup internet.

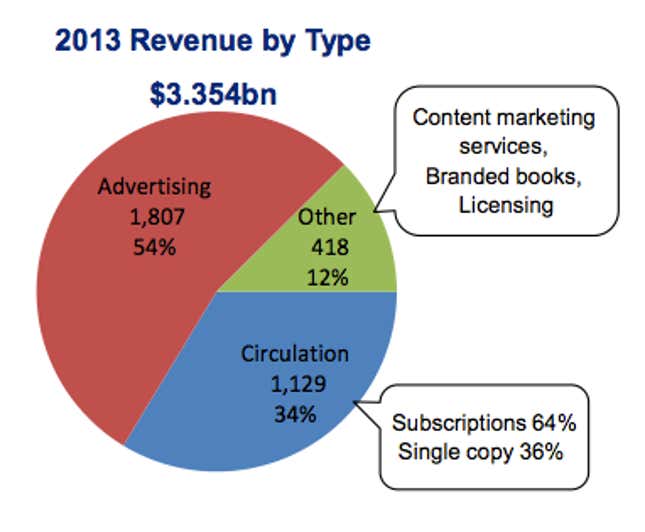

And now Time Warner is spinning off Time Inc, the publishing business on which it was founded. Why? Legacy print media companies are facing structural challenges from declining circulation and low advertising rates. As with all spinoffs, the idea is that the sum of the parts is greater than the whole. Time Warner’s valuation should rise, as it no longer has a print asset weighing it down. In theory, Time Inc. should also rise, with a more focused management team dedicated solely to magazine publishing. As a business, it has some attractive qualities. According to regulatory filings, Time Inc. generated $3.3 billion in revenue last year, and it expects that to grow by about 2% this year. It has a diverse portfolio of advertisers, and makes about a third of its money from subscriptions.

Evidently though, it’s a business that is not desired by the sprawling media conglomerate it once spawned. Time Warner is not the only media company retreating from print— Rupert Murdoch separated his film studios and television assets from his publishing empire this time last year. But while Murdoch allocated $2.6 billion in cash for News Corp to pursue acquisitions, Time Warner is saddling Time Inc with about $1.3 billion in debt, in part so it can it a reap a $600 million special dividend.

Time Warner’s empire remains vast: it has a market value north of $62 billion and owns some of the world’s best media assets, including CNN and HBO—and the pay-TV home of “Game of Thrones” might well be undervalued, as investors are only just now getting access to its financials. But the spin-off of Time surely brings a multi-decade period of empire creation and dissolution to a close.

The biggest winners from this endless financial engineering? Probably not shareholders, or its employees—Time Inc’s many journalists are certainly facing an uncertain future. The real winners, as usual in M&A, are the bankers and lawyers. If the various offshoots of Time are finally finished with their dealmaking then it would truly represent the end of an era for Wall Street as well. They will have to find a new meal ticket.