In the four years since he launched Jamalon, an online bookseller for the Middle East, Ala Alsallal has been noticing something. “Any book sold in the Middle East normally becomes boosted when a government bans it—it becomes a best-seller,” he says.

For example, consider Hadith al-Junud (“Soldiers’ sayings”), a novel by Ayman al-Otoum based on the 1986 Yarmouk University protests (pdf, p. 32-36) that pitted Islamist activists against the Jordanian authorities; published earlier this year, it has become a best-seller on Jamalon after being banned in Jordan, according to Alsallal. Censorship is so counter-productive, he says, that ”writers try to publish books that governments will not like so they can make more money.”

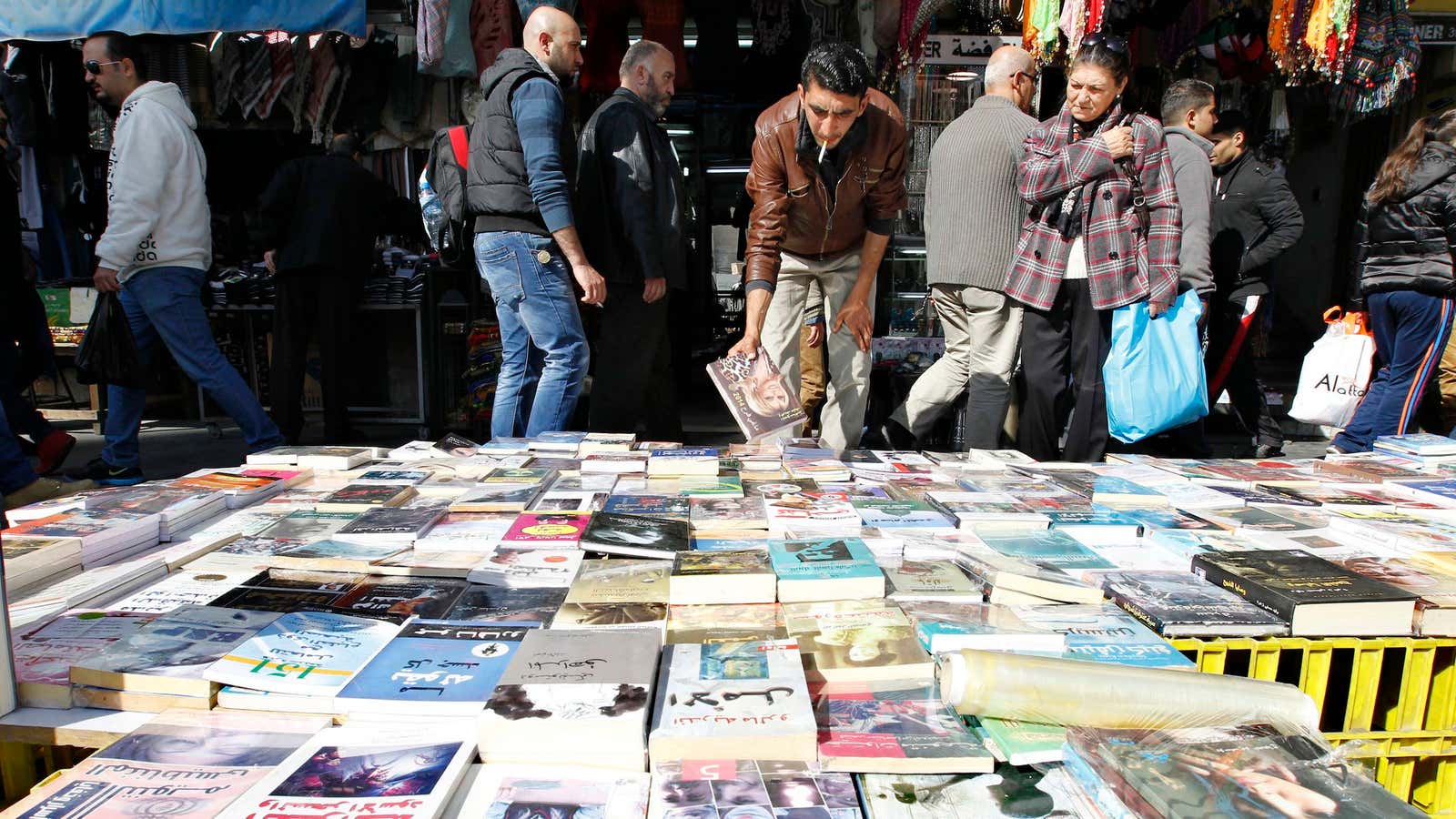

So Jamalon, which sells 10 million titles and serves over 20 countries, plans shortly to launch a new section devoted solely to banned books. The 28-year-old Alsallal, who spoke (video) at Quartz’s “Next Billion” conference on June 2, told us afterwards that he was inspired partly by a visit to the Strand Bookstore in New York City, where a table on the ground floor carries once-prohibited titles like William S. Burroughs’ Naked Lunch and Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita. (There’s a list on the Strand’s website.)

Most of those books are barely controversial in the West, but Alsallal says the authorities in Arab countries frequently ask Jamalon to stop supplying certain books to their citizens. To which he always gives the same response: “We have 10 million titles, and there are 50,000 new English books and 2,000 new Arabic books published every month. We cannot handle the filtering.”

According to him, Jamalon has not removed a single book from its platform. Governments can shut down domestic publishers or seize imported books at the border, but the company sometimes finds other ways to bring them in.

Ultimately, Alsallal is hoping to make banning books so futile that governments have no choice but to cease their attempts at censorship. The censors’ extreme conservatism sometimes works in his favor: Jordan’s censors caused some initial trouble for Our Last Best Chance: The Pursuit of Peace in a Time of Peril—a book, published originally in English, by none other than the country’s ruling monarch, King Abdullah.

Jamalon is also planning to launch an e-books division. These have been slow to get started, since digital files for many Arabic-language books—which are 80% of Jamalon’s sales—have yet to be created. But once e-books take off, they should confound the censors even more: Though governments can block offending webpages, tech-savvy Middle Easterners who are likely to buy e-books are also likely to be avid users of VPN apps that allow them to evade the censors.

And there is one more nail Jamalon hopes to hammer into the censors’ coffin: on-demand printing stations, like those made by Espresso Book Machine, that can produce any paperback book in minutes. “Our aim is to put one of those in every Arab country,” Alsallal says.