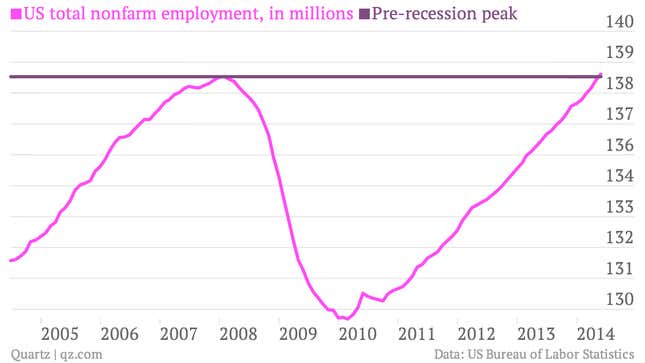

Evaluating the financial crisis and Great Recession is an exercise in benchmarking. Today’s US jobs report is a good example: While employment finally reached levels last seen before the housing bubbled popped—huzzah!—the relative share of people who are employed remains far below the pre-recession trend—boo! Every sign of progress can also be seen as a failure to meet potential.

That’s why, for all the attention that former US Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner’s recent narrative apologia for American financial policy has received, you should turn to Tufts University political scientist Dan Drezner’s new book, The System Worked: How the World Stopped Another Depression, for a wider view. Like Geithner, Drezner’s depiction of these events, warts and all, makes the case that global economic governance helped pull the fat from the fire.

“In some ways, the informal title for this would have been ‘it could have been so much worse,'” Drezner says. “Look, the performance was sub-optimal, but it wasn’t sub-par.”

What prompted the book, Drezner tells Quartz, were his own low expectations before the 2008 crisis: He was planning a book predicting the breakdown of the global economic order. But when the crisis came, global economies defied his expectations. They coordinated through the G20 group of nations to launch a worldwide stimulus program, avoided protectionism in trade policy, and pushed for stricter international standards for banks. Rather than a repeat of the Great Depression, when trade withered and economies adopted beggar-thy-neighbor policies, we got away with just a Great Recession—and one that many emerging markets bounced back from quickly.

Take the G20’s coordinated stimulus. It was a big deal in 2009, and in part it came about because of interdependence—Drezner cites Apple’s supply chain, which led the US to send $1.9 billion to China in 2009 for iPhones alone. Unlike in past periods, when trade failed to operate as a unifying force (before World War I, say), today’s trade isn’t just finished goods between countries: China imports 96% of the materials and components necessary to build an iPhone. That level of micro-integration arrayed interests, not just in China but in a community of countries, against cutting back on participation in the global economic system.

But wait—wages, growth and jobs are still lagging in the United States and the European Union. That has a lot of those countries’ citizens blaming globalization and the institutions that support it, such as the International Monetary Fund. Don’t blame globalization, Drezner says: Blame your governments.

In the recovery stage of a financial crisis, growth is expected to be slow—clearing debt off balance sheets takes longer than responding to other kinds of shocks. Hastening growth requires policies that were not fully adopted in either the US or Europe, as austerity dominated policy debates. (It’s worth noting that the IMF was long a critic of US fiscal policy, calling for more near-term stimulus and longer-term efforts to deal with debt.) And the EU, with its mixed record of addressing its own debt crisis and recession—Drezner calls it “an unmitigated disaster”—is more of an actor in global governance than an example of it.

In developing economies, which didn’t suffer from the same balance sheet problems, recovery has been faster—and citizens are commensurately more optimistic. And, Drezner says, the developed economies are set for more expansive growth. There are good signs that global governance will get stronger. For one, institutions are adapting: the IMF has relaxed some of its traditionally neoliberal arguments and is a more broad-based institution; the G20 provides a platform for the BRICs and the G7 nations to coordinate; Basel III has put a floor on bank regulation. For another, countries are recommitting to the global system with a flurry of bilateral and regional trade deals under discussion, even if Edward Snowden’s revelations have clearly chilled US talks with Europe.

Of course, there are other worrisome signs. Where politics trump economic interest, global governance can be weak: Everyone looks warily to trouble-spots such as the South China Sea and Crimea, where tensions run high. But Drezner seems less worried. He notes that for all its territorial probing, China has been a responsible economic stakeholder; in Crimea, Russia’s aggression has been checked by the amount of capital leaving the country, even if its ability to hang on to the seized territory suggests fraying around the edges of the international system. And some security problems—notably piracy at sea—have been met with a decisive global response. Of course, that still leaves climate change and inequality, two challenges that may be unaddressable with current institutions.

Drezner—also the author of a popular tome on zombies and international relations—acknowledges that sometimes a glass-half-full analysis makes a theorist more vulnerable to criticism. In academia and journalism, pessimism becomes mere prudence if your prediction is wrong, while false optimism makes you “the next Norman Angell.”

But for all Drezner’s concern, there’s something to be said for an honest evaluation: A diverse array of countries surprised nearly everyone with their willingness to bond together, at least briefly, in the interest of saving the world economy. It’s worth studying why and how that happened.