(Warning: this post contains a graphic image.)

Traditional Chinese medicine has been responsible for threatening the populations of rhinoceroses, pangolins and snub-nosed monkeys. Add another animal to that list: rays.

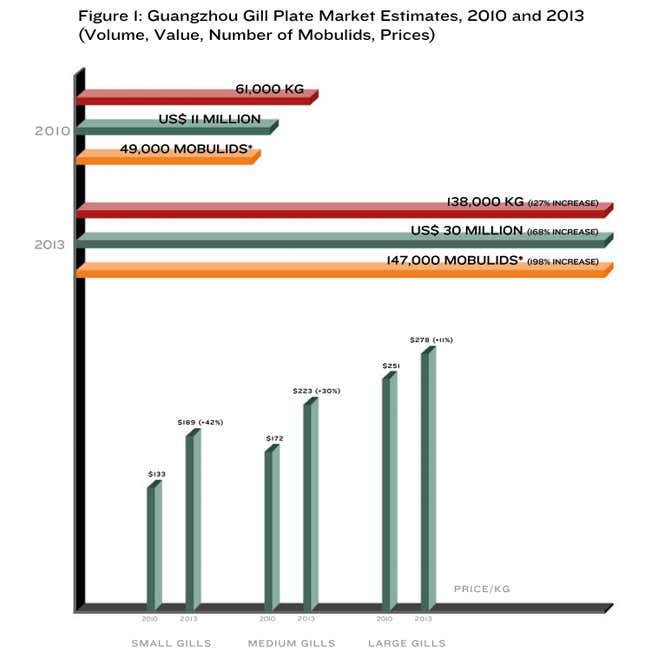

Rays are like the 40-year-old virgins of the fish world. Their reproductive sluggishness is part of why they can’t replace the number that are killed. The bigger factor, though, is surging Chinese demand for their gills, which are prized as a traditional remedy. Prices for their gills have jumped 168% since 2010, says WildAid, a conservation group, in a new report (pdf).

Bad for rays—but bad for people too. Rays’ gills can contain arsenic, cadmium and other lethal metals, but traditional Chinese medicine peddlers promote them specifically to breast-feeding new mothers. Meanwhile, ray-slaughter threatens the $140 million in annual revenue from ray-focused dive tours—much of that in poor coastal African and Asian economies that need the tourism revenue.

A goldmine in their gills

Manta and mobulid rays feed by filtering food through cartilaginous sieves inside their gills. Stewed as a health-tonic soup (link in Chinese) prized in southern traditional Chinese medicine, these “gill plates” or “gill rakers” are carved out of the carcasses of mantas, sicklefin devil rays, or spinetail mobulas (killing for the gills of other mobulids are less common).

Fishermen can pocket between $40 and $500 for the gill plates of a single manta ray. The rest of its parts have little commercial value, though fishermen can sometimes make a extra few dollars selling the meat for use in fake scallops and animal feed, and the skin to make boots and wallets.

Health elixirs and lactation aids: a booming market

Merchants in the southern city of Guangzhou, where most of the trade takes place, say they’re now selling twice what they did in 2010, according to WildAid, which surveyed more than 1,100 vendors in 2010 and 2013. WildAid estimates the industry is now worth $30 million, up from $11 million in 2010 (pdf, p.3).

Why the surge? Despite their absence from official traditional medicine manuals, gill plates are sold as detoxifying agents and immune-system boosters, as well as treatments for childhood chicken pox. More recently, though, vendors have begun recommending the remedy as a lactation aid for new mothers. (Shunned for decades in China, breastfeeding is now gaining in popularity, in part thanks to government promotion.)

Gill plates go mainstream

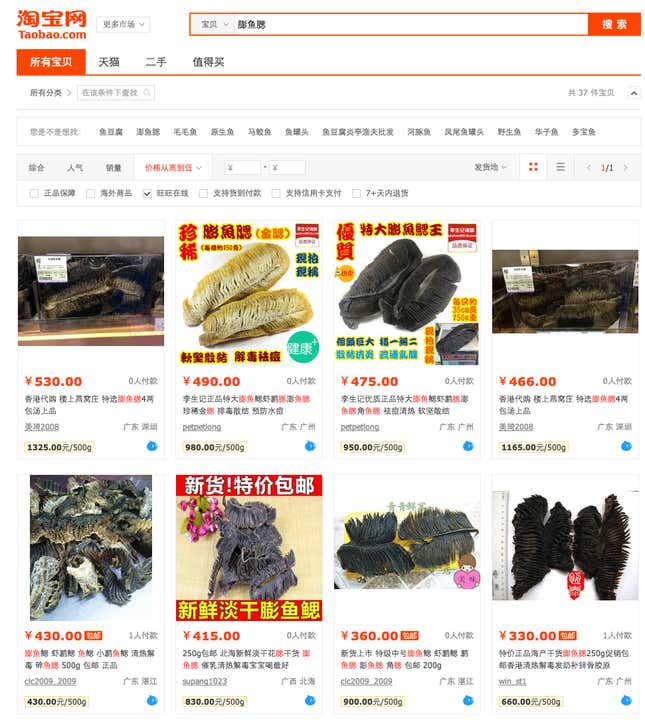

Then there’s how they’re sold. The last time WildAid investigated, gill plates were mainly marketed to consumers in brick-and-mortar stores, like this one:

Since then, the remedy has gotten mainstream media airtime, including a special on a popular TV show featuring a cooking demonstration and discussion of the health benefits of gills by a pharmacist from a local hospital, reports WildAid. (This is despite the fact that official guidelines don’t recognize its medicinal effect.) They’ve also become more widely available online:

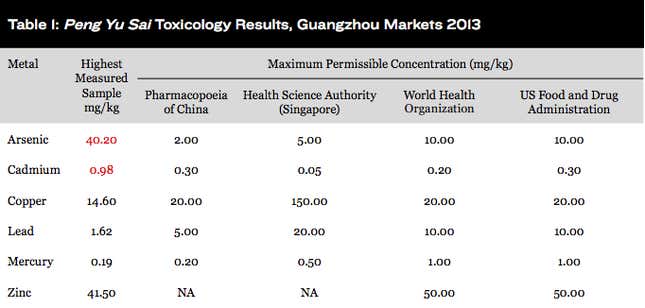

Packed with arsenic, mercury and other deadly heavy metals

The market’s rapid expansion is particularly alarming, given what an independent lab found in toxicology tests of gill plates: That all samples of manta and mobula gill plates taken from Guangzhou markets contained arsenic, cadmium, mercury and lead.

Even in small amounts, mercury threatens children’s development in utero and in early life; the levels of arsenic and cadmium the lab found in the samples can cause cancer and damage kidney function. An online survey of Guangzhou consumers by WildAid revealed disquieting results. Far from being a luxury wonder drug—the way, say, pangolin parts are—the biggest consumer of gill plates are working women trying to keep their families healthy.

$500 now… or $1 million later?

A patchwork of laws around the world protect manta and, to a much lesser extent, mobula rays (even though scientists have no population data on the two mobula species commonly killed for the gill-plate trade). However, fishing vessels in Sri Lanka, India, Mozambique and Peru, among other places, still actively target rays to capitalize on Chinese demand.

WildAid is suggesting another way of calculating the rays’ value: For tour guides, that same animal that fishermen could sell for $40 and $500 would generate $1 million in dive-tourism revenue over its lifetime, says the conservation organization. That tension between the fisherman’s instant gratification and the tour guide’s long-term business is straining poor coastal economies.

For instance, in Mozambique’s Inhambane Bay, one of the biggest dive destinations in the world, manta ray numbers have shrunk by 87% in just a decade, say scientists. Back in 2004, dive tourists encountered an average of 6.8 rays per dive; by 2011, that had fallen to 0.6 (pdf, p.34).

Some countries are stepping up protections. The Indonesian government is working on legislation to create the planet’s largest manta ray sanctuary. And last week, the Maldives took an even bolder step. The heavily tourism-dependent island nation, which has the world’s biggest manta population, banned the capture or harm of any of the 18 types of rays in its waters. “Rays have gotten so rare now that we fear its extinction, when it earns a lot of profit in tourism,” said Ibrahim Naeem, head of the Maldives’ environmental protection agency.