Listening to criticism of Brazil’s ham-handed preparation for the World Cup, Indians couldn’t help but hear echoes of 2010, when they hosted the Commonwealth Games and were embarrassed by slipshod construction and kickback scandals involving officials who paid $80 for rolls of toilet paper. Charges of incompetence often haunt big-event organizers, but Brazil and India are now responsible for two of the most poorly planned athletic spectacles in memory. Though Brazilians are shifting from complaining about this $11 billion embarrassment to cheering their team, the aftershocks could be far reaching, as they were in India.

Despite the 8,000 miles that separates these nations, India and Brazil move to a common rhythm, and that bond is currently more visible than ever. In India, the Commonwealth Games came to be seen as a surprising success, but the scandals helped to ignite an anti-government revolt that culminated in the crushing defeat of the ruling Congress Party in May. A similar scenario could unfold in Brazil, where popular anger over the money lavished on the Cup, when roads and schools go underfunded, set in motion huge anti-government protests last summer. The anger lingered even after the “Seleção“—the Brazilian national team—took the pitch and the opposition parties sensing that the incumbent Dilma Rousseff is vulnerable in the presidential elections scheduled for this fall.

The opposition movements in India and Brazil spring in part from the roots they share as “high-context” societies, a term coined by anthropologist Edward Hall to describe cultures in which people tend to be colorful and talkative, but to dodge blunt conversations and to be casual about deadlines. These societies favor the in-group, whether it is one’s family or business circle, and are thus prone to the kind of corruption and delays that have dogged big events in high context countries like Greece, India and Brazil. A month before India played host in 2010 the CEO of the Commonwealth Games described the athletes’ village as “filthy and uninhabitable.” In the run-up to this World Cup, a top FIFA official said Brazil needed a “kick in the backside” to be ready in time.

In contrast, people in low context cultures like Germany or Britain tend to have less flair, be more organized and to finish projects in timely fashion. One Croatian football fan told Reuters in Rio that, having experienced “order” at the 2006 World Cup in Germany, she wasn’t worried about delays or protests. “This is Brazil,” she said. “I want it to be a little crazy.”

Asian countries—where speech is indirect but discipline is strict—are often a mix of high and low context. These cultures do produce very different results: China, Japan and Korea have staged Olympic and World Cup events with few if any complaints about dirty rooms or unfinished stadiums. Rousseff tacitly acknowledged those differences when, defending the construction delays, she said, “Nobody does a subway in two years… Well, maybe China.”

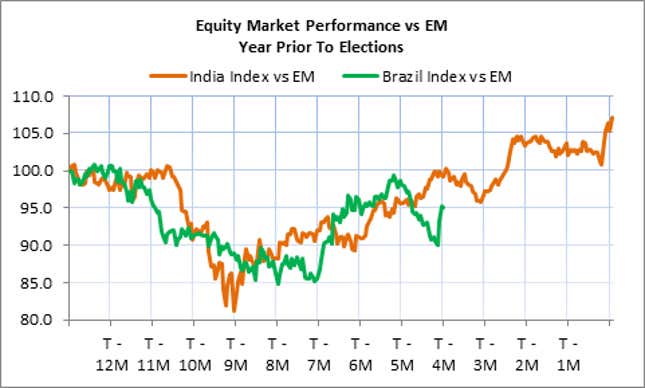

Many Brazilians are fed up with “a little crazy,” and they see hope for change in the example of India. There, popular disgust with the Congress party’s mismanagement of the economy led to its May defeat at the hands of Narendra Modi, a strongman state governor with a reputation for running an efficient government. Brazilian investors now look at how the stock market has surged behind Modi and figure an opposition win can trigger similar results in Brazil. The market has rallied nearly 30% since March, when Dilma started to drop in the polls, and it is following a path that mirrors the one charted in India before the May election.

These societies are now moving in lockstep, with middle classes convinced that it’s time to overhaul an economic model with socialist roots. The stock markets are rising in Brazil and India despite few signs of improvement in their economies, which share a history of heavy welfare spending and weak investment in basic services—one reason the money lavished on sports is so controversial. The weak infrastructure networks make these nations vulnerable to stagflation. Brazil’s economy is expected to grow at barely 1% this year with 6% inflation. Yet Brazilian investors aren’t talking about the economy, only about how Rousseff is fading.

The leading Brazilian opposition figure is Aecio Neves, who like Modi was a state governor known for getting things done. His finance minister would be Arminio Fraga, a key member of the team that in the 1990s helped contain hyperinflation, the cancer that still threatens other high context societies like Venezuela, at a time when Brazilian businesspeople worry openly that ill-advised government spending is turning their country into “the next Venezuela.” So even as Brazilians come to embrace the World Cup, they may still opt for a new leader as the country’s economic woes continue to mount.