Somewhere between the first protest over transit fare hikes in Sao Paulo and president Dilma Rousseff’s public address three weeks later, football and the Olympic Games found themselves swept into the heart of Brazilian anger.

The outcry had centered around failed social services, corruption, and misplaced expenditure. As the crowds grew from tens of thousand to a million-strong on June 20, Brazil’s two biggest sporting show pieces—the 2014 World Cup football and the 2016 Olympic Games—were turned into symbols of everything wrong with the government and the country’s elite.

On the day of the Confederations Cup (a preparatory event for 2014) semi-final, between Brazil and Uruguay in Belo Horizonte, 50,000 clashed with police a few miles from the stadium. In Brasilia, a peaceful yet more symbolic protest took place as the crowds kicked footballs over a police cordon—and toward the Congress.

Until Brazil’s winter of discontent, most criticism in countries hosting football World Cups or the Olympics tended to emanate from a relatively small fringe group protesting escalating costs and tax burdens.

In Brazil, though, what the world saw was protest against the world’s two biggest sporting events on a gigantic, unprecedented scale. On a scale that fittingly almost belonged to the dizzy perch that the Olympics and the World Cup occupy in the hierarchy of “eventism.”

The roar of outrage against the World Cup has come from a nation tied into the sport, which writer Alex Bellos calls, “the strongest symbol of Brazilian identity.” In Futebol; The Brazilian Way of Life, Bellos writes, “no other country is branded by a single sport … to the extent that Brazil is by football.”

The June demonstrations proved that Brazilians have put their beloved football in its place. Firmly behind what eventually matters more: education, jobs, health services, security.

Rousseff and FIFA president Sepp Blatter were booed during the Confederations Cup opening. The world’s most celebrated footballer Pele was shouted down after his taped video message said, “Let’s forget all of this mayhem that’s happening in Brazil, all of these protests, and let’s remember that the national team is our country, our blood.” On social media, Reuters reported scathing responses: “Pele, your ignorance is in proportion with your footballing genius.” “Go to the hospitals, take a bus with no security, then I want to see if you keep saying stupid things.”

This month’s consequences will play themselves out for Brazilians between now and kick-off 2014. The most beneficial fallout on the rest of world, though, could be if June 2013 calls time on the gargantuan size and cost of world sport’s high-priced “mega-events” particularly in developing nations and their growing economies.

It is no coincidence that in the last five years the “BRICS” nations have either bid for or hosted mega sporting events.

- Brazil [B] will host the World Cup and the Olympics

- Russia [R] will host the 2014 Winter Olympics and the 2018 World Cup football

- India [I] staged the 2010 Commonwealth Games, bid for the 2014 Asian Games and, despite its weak footballing structures, is once again bidding for the under-17 World Cup football.

- China [C] hosted the 2008 Olympics

- South Africa [S] the 2010 World Cup football.

In 2018, PyeongChang, Korea will stage the Winter Olympics. The rivals to India and its under-17 World Cup are Uzbekistan, South Africa and Ireland. The 2022 World Cup will be held in Qatar.

Perhaps the economic grind has led developed countries to arrive at a more realistic appraisal of what hosting mega events really means. The number of bids for the Olympics has been decreasing in the last 20 years. In 1993, the five candidate cities for the 2000 Summer Olympics turned to four in 2009 for the 2016 Games. For 2020, the list is down to three—Istanbul, Madrid and Tokyo.

In October 2012, a new coalition government in Netherlands scrapped the country’s bid for the 2028 Olympics in its policy blueprint saying hosting the Games brought “financial risks. There is little support for this in a time of crisis and austerity.”

In March this year, the Swiss canton of Graubünden voted against allowing Davos and St. Moritz to bid for the 2020 Winter Olympics. Switzerland is the home of the International Olympic Committee and its own citizens didn’t believe the claims that the winter Olympics would “help tourism and boost the local economy.”

That is the classic “booster” claim that lures countries and cities to bid for mega events. The booster offers civic add-ons like improvement in airports, roads, public transport, sports facilities. What should be civic and national administrative duties in the first place are turned into privileges made available to mega event hosts. Tied in with this comes the growing economy’s desire to advertise its arrival among the “high table” of nations with the creation of “world-class” host cities.

The storyline of mega events has turned into a tired, formulaic script, which in real terms, has dire results on real people. The development of either sport or the economy is peripheral, the mega event becomes a private sector gravy train whose costs of operation are borne by public funding.

Residents of New Delhi, the host city for the 2010 Commonwealth Games, can see patterns and predictive paths in Brazil 2014 and 2016.

When a bid is won, citizens are promised that the mega event will involve not a single cent of public money. As cost overlays and delays pile up, the national exchequer is leaned upon to restore national “pride” and prevent the country’s global reputation from being that of a laggard.

In New Delhi, the Games Organizing Committee had been expected to generate private sponsorship worth Rs1200 crores (roughly $200 million at the time). Four months before the Games, a mere Rs342 crores ($62 million) was generated before the government asked leading public sector firms like the oil companies to chip in. As New Delhi prepared to host the 2010 Commonwealth Games, conscientious objection around it pertained to escalating costs, the flouting of environmental and labour laws and displacement of the marginalised.

These could have been refrains from Athens 2004 where hosting the Games cost $11 billion, twice what had been budgeted, of which $7 billion was billed to taxpayers. The collapse of the Greek economy may not have been directly related to the Games, but in December 2011, even IOC chairman Jacques Rogge told Greek newspaper Kathimerini that it could “fairly” be said that “the 2004 Olympic Games played their part” (in Greece’s debt crisis). “If you look at the external debt of Greece, there would be up to two or three per cent of that which could be attributed to the Games.”

During the 2010 Commonwealth Games, he had informed thrilled Indians that the country had “set a good foundation stone for the Olympics bid.” Rogge said with a straight face: “a successful Commonwealth Games can help India mount a serious bid for the Olympics.”

One of the most bandied about catch phrases by the mega-event PR machine is the “legacy” left by the mega-event. The idea of legacy itself is left rusting around host cities and countries.

Beijing 2008 were the most expensive games costing around $40 billion, but the stadiums once called modern architectural marvels are now struggling to keep themselves sustainable and relevant. Two years later, South Africa spent $5.5 billion on staging the World Cup and finds its new stadiums, particularly in rural Polokwane and Nelspruit, far too large for towns without teams playing in the country’s top flight domestic league.

In the runup to London 2012, Reuters photographers produced a slideshow called Ghosts of Olympics past to indicate the desolation of sports venues that had not so long ago hosted the world’s best athletes.

Debates of the sustainability of the 2010 projects were met with negative reports after the Commonwealth Games. Its top three officials went to jail under corruption charges and rather than create a surge in Indian sport, India was suspended by the International Olympic Committee in December 2012.

London 2012 was meant to be a green, sensible-new-millennium kind of games. The general do-gooderness of the 2012 master plan even prompted a BBC TV show called TwentyTwelve centered around the Games “deliverance” team, including a “Head of Sustainability” with a catch phrase: “Sustainability is not the same as legacy. It is not.”

Yet in April 2012, Britain’s National Audit Office said that public sector funding of London 2012 tripled while private sector contributions had dwindled to 2% of the total bill, £11 billion. Its post Games report (pdf) billed the public sector funding package at over £9.2 billion, with more than £500 million spent on security. The private firm given the security contract threw up its hands months before the Games, and ‘fessed up that they couldn’t supply the personnel.

In these woeful examples lie echoes of what could well be Brazil’s future. The protests are merely an early response to what lies ahead (without the BBC jokes). Brazil in fact ended up being the only bidder for 2014 World Cup after Colombia backed out in 2007. Brazil’s then-sports minister Orlando Silva had promised that stadium construction and renovation wouldn’t cost the public.

Seven years later, Brazilians will have to pay more than 90%. With the recent history of mega events in mind, that was an almost predictable deceit.

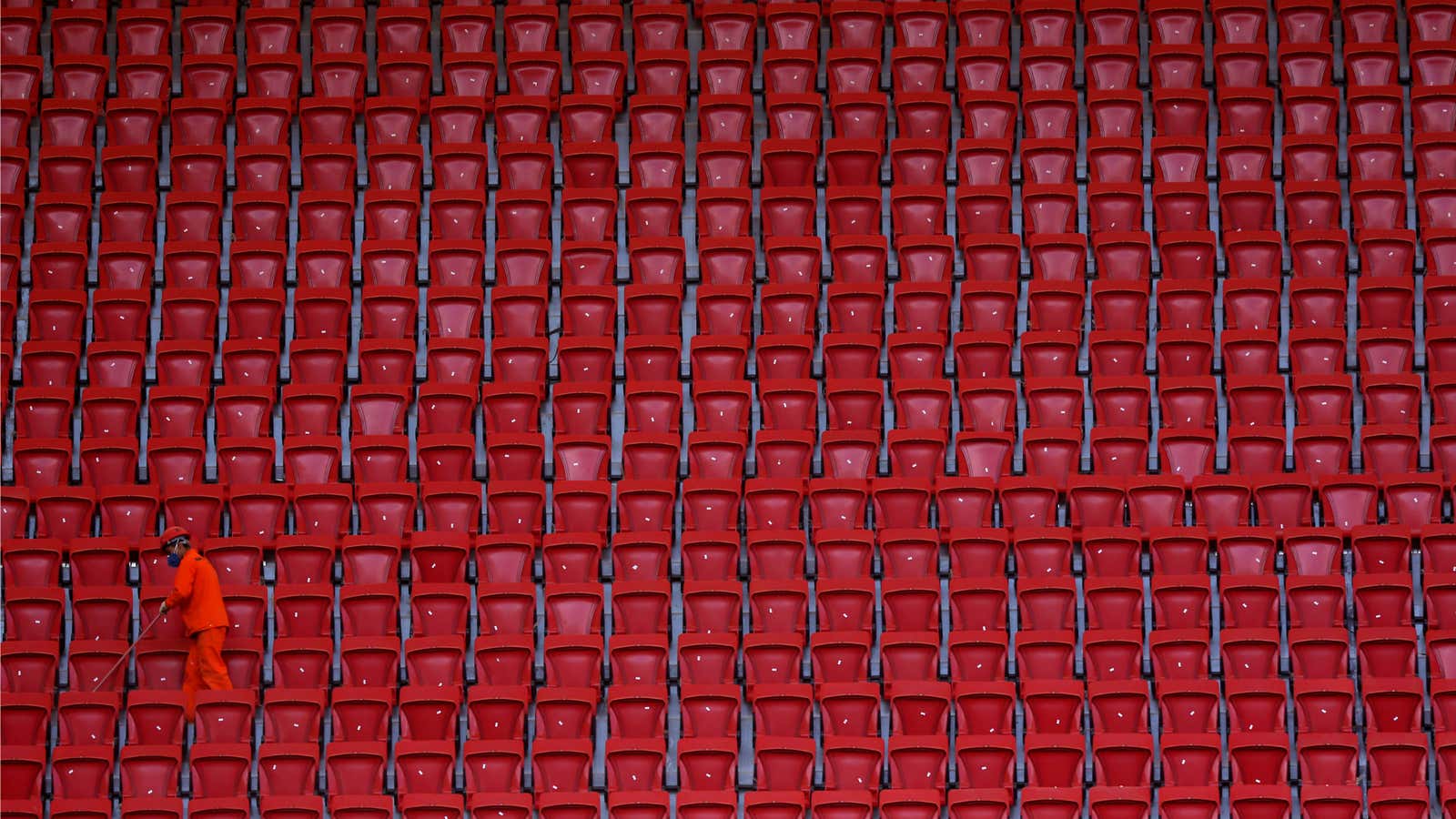

Twelve stadiums are being either newly constructed or renovated for 2014. Brasilia, whose football team attracts no more than a few hundred fans, will be given a 71,000-seater. Cuiaba and Manaus, which like Brasilia do not have local clubs that feature in the top two tiers of the domestic league, will suddenly have stadiums that can fit in 40,000 ghost spectators.

The stadium in Fortaleza, the fifth most unequal city in the world according to the UN, will cost more than $220 million to be renovated and more than 5,000 people have already been moved. A local resident told the Guardian that people were asking, “Who is the World Cup for?” A political scientist called it the “theatre of the authorities.”

In the developing world, the mega-event has been turned by the organizers into “bread and circus” metaphor that Roman poet Juvenal rued over almost 2,000 years ago. Except Brazil reminds us that even bread is not so much of a given any more.

Analyzing mega-events, a business professor once said, ”One must balance the questions of improving the daily livelihood of the common man with the so-called national prestige that only the pampered urban elite care about.” Only his name tells us the event he was referring to. It doesn’t matter though. Rajesh Chakrabarti of the Indian School of Business in Hyderabad could have been talking about Brazil 2014 and Rio 2016.