Anything that can be faked profitably, will be faked. Art, memorabilia, luxury goods, you name it. Wherever a big gap exists between material expenses and retail value, forgers will find a way to imitate products well enough to deceive gullible customers. Given that the difference between input costs and sticker price is greatest for high-end paintings, it is unsurprising that the art market is bedeviled by forgeries.

These thoughts are inspired by accusations and counter-accusations swirling around a recent sale by the Bangalore-based auction house Bid & Hammer. A number of experts questioned the authenticity of a Rabindranath Tagore painting titled Nritya, among other works in the sale. The Tagore closely resembled a painting in the collection of the institution Rabindranath founded, Santiniketan’s Visva-Bharati University. Another lot, Nandalal Bose’s Woman Sitting Under a Tree, appeared identical to a painting in the National Gallery of Modern Art’s collection. Also questioned was the authenticity of paintings by stalwarts like K. H. Ara, M. F. Husain and Bikash Bhattacharjee.

The reaction of those in the art industry, such as Ashish Anand of Delhi Art Gallery and Arun Vadehra of Vadehra Art Gallery, was to suggest the setting up of an official regulatory body and authentication committee. It is curious how Indians, who never tire of holding forth about the incompetence and corruption of government, seem always to conclude that the solution to any intractable problem lies in the setting up of a government committee. Those in the trade should be careful what they wish for, because, should the government actually create a authentication panel, it will almost certainly be a disaster. For example, we can expect demands for original works to be shipped to the Capital for inspection in a process that will take months, since committees constituted of authorities living in different regions of India can’t be expected to meet every week. At the end of it, there is no guarantee that forgeries will always be spotted, or that authentic works will always be certified as such, since these things often come down to a matter of opinion. And opinions differ, even among impartial experts.

In actual fact, Indian art requires less, not more, regulation. Expertise and transparency have been strangled by the Antiquities Act, which makes the owning and selling of antiquities difficult, their export illegal, and restricts trade in the work of a number of modern artists labeled national treasures, Rabindranath Tagore and Nandalal Bose among them. While there is no silver bullet solution for the problem of forgeries, partial fixes emerge as a natural consequence of trade. Buyers develop relationships of trust with dealers. Certain individuals receive widespread recognition for their connoisseurship, and become established authenticators. Foundations publish catalogues raisonnés, which are comprehensive listings of all known works by artists. This last has never happened in India, partly because of the huge expense involved, partly because many collectors don’t wish to reveal the extent of their holdings, and partly because family members of dead artists, who often become the authenticators of choice, want to make the most of that privilege.

Even in places where catalogues raisonnés and impartial foundations are common, the problem never disappears. As a market grows more lucrative, there is greater pressure put on authenticators, in some cases growing to breaking point. The Andy Warhol Foundation no longer authenticates works by the Pop art genius, who is, in terms of total annual sales value, the biggest-selling artist in the world. Last November, a painting by him titled Silver Car Crash sold at Sotheby’s in New York for $105 million and change. The exploding value of Warhols makes every decision about authenticity worth a fortune. A few incensed owners of works refused a certificate have in the past taken the Foundation to court. Litigation costs grew so high, and the potential consequences of losing a trial so onerous, that the Foundation’s trustees concluded the whole authentication business had become a mug’s game.

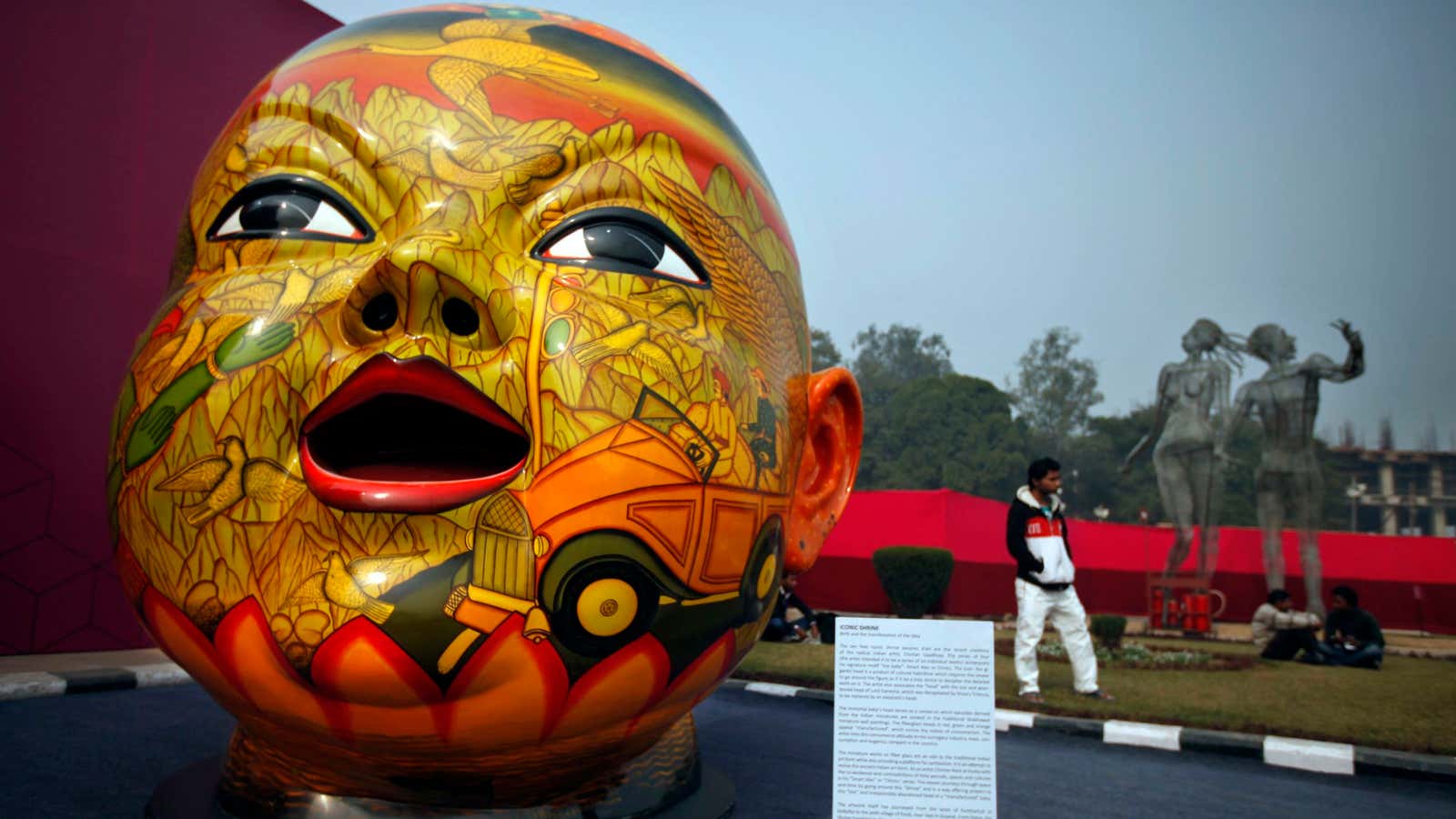

Where the authenticity of antiquities is concerned, technology comes into play. Most attempts at deception can be unmasked by accurately dating materials using techniques like thermo-luminescence. Yet, consensus remains elusive. A case in point is the pottery of Chandraketugarh, a region in Bengal from which an astonishing number of gorgeous two thousand year-old terracotta objects has been excavated. As demand for them rises around the world, many farmers have chosen to dig up their land rather than till it. Smuggling flourishes, and, naturally, forgers have emerged as well. Making fake Chandraketugarh pots and plaques is apparently a cottage industry in Calcutta. A few Chandraketugarh pieces divide even the foremost experts. If they are fakes, they are such exceptionally fine ones, that the forgers deserve our admiration.

While on forgery, it is worth recalling that the greatest sculptor in the history of the universe flirted with fakery. Back in the 15th century, Italians had developed a taste for statuary dating from the days of the Roman Empire. This was an unusual development, since, in most times and places before then, and in much of the world for centuries after, old, broken artifacts were considered worthless. Seeing a marble cupid produced by a 20 year-old wannabe named Michelangelo, a Florentine art dealer suggested he age it with acidic earth to pass it off as antique. When the deception was eventually discovered, the buyer of the piece invited Michelangelo to Rome in appreciation of his skill, and introducing him to patrons there, kick-starting the young man’s artistic career.

To return to the Bid & Hammer case, there is at least one positive thing to take away: it demonstrated once again the value of an auction process. By placing images and information in the public domain, auctions invite questions about provenance and authenticity in a way private sales never can. When doubts are raised, as they were in this case, prospective buyers adjust their plans. Those who bid for controversial works will have only themselves to blame if these are later shown to be fakes.