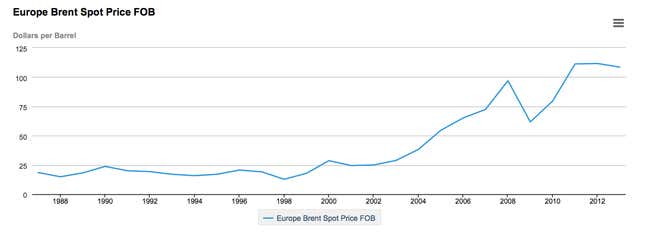

Oil prices dropped again today, but that doesn’t mean they are low. Indeed, at above $100 a barrel, they’re still at historic highs, as they have been for three years.

The main reason for these elevated prices is the exceptional surge of local disruptions in oil-producing regions around the world—the overthrow of governments in the Arab Spring, the chaos of Nigeria, the turbulence in Ukraine, and the breathtaking territory-grab by ISIL in Iraq, to name a few.

How long can this level of collective commotion go on? A decade and perhaps longer, according to many of the world’s top energy analysts.

The latest to weigh in is Wood Mackenzie, the Edinburgh-based energy research firm. “No one is expecting a return of calm in the Middle East,” WoodMac’s Paul McConnell tells Quartz. The firm’s projection bakes in five to 10 more years of such disruptive events in the Middle East and North Africa.

Quartz wrote about this trend last month. While oil prices continue their slide today, with Brent crude tumbling to $106.45 as of this writing, they are prevented from descending into free-fall by the geopolitical disruptions noted above, which have idled some 3 million barrels of oil production capacity.

In a report today, the International Energy Agency (IEA) said that the 1.2-million-barrel-a-day increase in oil supply that it expects from the US and Canada next year will more or less meet a 1.4-million-barrel-a-day rise in projected global demand. But the agency said the turmoil around the world could throw off that alignment. The suggestion is that if more oil goes off the market because of mayhem, prices could shoot up again.

“Supply risks in the Middle East and North Africa, not least in Iraq and Libya, remain extraordinarily high,” the IEA’s report says. “Whether in crude or product markets, there is little room for complacency.”

The ramifications of the forecast are important. Before the ISIL offensive, for example, WoodMac had been projecting a ballooning of OPEC’s spare production capacity to about 7 million barrels a day by 2020, almost triple the current level of about 2.5 million barrels.

Spare capacity is the main determinant in oil prices because of the law of supply and demand—idle capacity that can be brought quickly into production allows the market to absorb disruptive events. If there were such a sustained swelling of surplus capacity to 7 million barrels a day, we would almost certainly see a plummet of oil prices.

But the ascent of ISIL has led WoodMac to reappraise its forecast, McConnell said. In a note to clients, Barclays said the turmoil creates the danger of a tremendous price surge like what occurred in 2008, when oil went to $147 a barrel.

“Problems in Iraq come at the worst possible time for oil as the global economy is picking up momentum, oil demand growth embarks on a seasonal upturn and spare capacity continues to shrink,” Barclays said. “Oil markets are finely balanced and the risk of a price spike is greater than at any point since the start of the financial crisis.”