To residents of the southwestern United States, the rising incidence of drought in recent decades has made speedy showers and yellowing lawns facts of life. Little do they know that things are about to get worse still. A new study (pdf) shows the Colorado River Basin, the southwestern US’s only major river, is drying up far faster than even scientists realized—and at a rate far quicker than mountain snowmelt can replenish it.

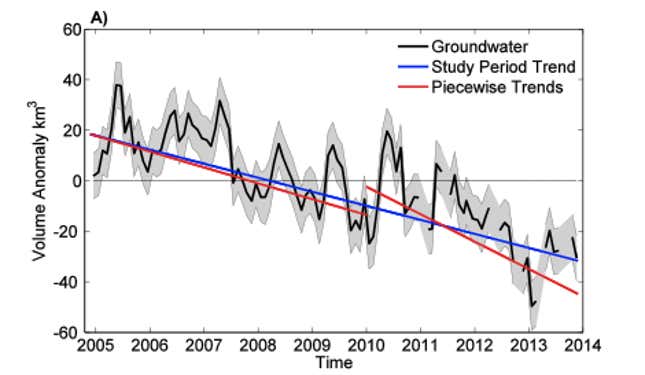

A critical water source for some 40 million people in seven states, the Colorado River Basin lost nearly 53 million acre feet (65 cubic kilometers, or 17.2 trillion US gallons) of water between Dec. 2004 and Nov. 2013—almost twice the volume of the US’s biggest reservoir, Lake Mead.

“This is a lot of water to lose,” said Stephanie Castle, a water resources specialist at the University of California, Irvine, and the study’s lead author. “We thought that the picture could be pretty bad, but this was shocking.”

Most alarming of all is that more than three-quarters of that was groundwater, as opposed to water above ground (such as in reservoirs). So difficult is it to replenish those underground wells that it suggests that the region’s freshwater supply is now in a state of irrevocable decline.

How did this happen without anyone noticing it? The answer, basically, is that up until this study, nobody had a good way of measuring how much water is stored underground.

The great depletion

The literal source of the problem is the 1,500-mile-long gush of Rocky Mountain runoff that forms the Colorado River. Though it once tore through the western US with such force that it etched the Grand Canyon, the river was no match for the Hoover and other dams. Put up in the 1920s to slake the thirst of cities like Los Angeles and Phoenix, those dams form huge reservoirs such as Lake Mead.

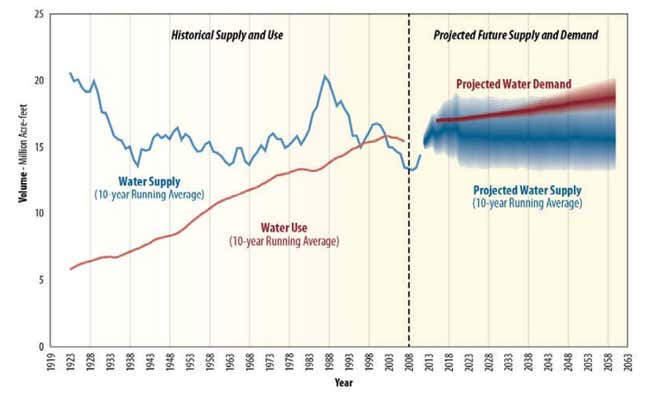

It’s not hard to notice that demand for this water exceeds supply. Back in 1920, only about 5.8 million people relied on the basin for water; now it’s nearly seven times as many. The river basin also irrigates what has grown to around 4 million acres of farmland. And just looking at lake levels tells you that it’s time to cut back on water use. Here’s Lake Mead:

Plus, federal water managers document and ration the entire supply of the basin’s above-ground reservoirs. Here’s what they’ve projected:

But it’s much harder to know how much water’s left in underground wells, which is replenished when surface water seeps through the soil. What’s more, the federal government leaves regulation to individual states, which, frankly, do a lousy job of keeping track. California, for example, has no groundwater management rules at all.

The problem is that when above-ground water supplies run low—as often happens in California, even when there isn’t a drought—water managers use groundwater to meet public and farming needs.

The big breakthrough in the study, which UCI conducted in tandem with NASA, was that it tracked changes in underground water reserves over time, by taking gravitational readings. The findings? So much groundwater has been used that it will be impossible to recover it naturally; overall supply of available freshwater will continue to decrease as a result.

By reducing snowmelt in the Rockies and causing more droughts, climate change will only exacerbate this scarcity. That’s a scary thought given how much droughts are already straining the public’s water needs. Angelenos, for instance, have been asked to slash daily water usage by 20%—to 126 gallons a day. And as this new research suggests, even that’s probably not enough.