The population of the Philippines hit 100 million this week with the birth of a baby girl. Its central bank also raised interest rates for the first time in three years to guard against inflation, even as the economy slowed down—two milestones that underline the fast-growing Southeast Asian country’s economic potential, and its challenges. The Philippines is home to one of Asia’s youngest and fastest growing populations. The country is not expected to reach its demographic peak until around 2077, well after China, South Korea, and other powerful economies in the region.

But the Philippines may never enjoy its demographic dividend if poverty, unemployment, and inflation aren’t addressed. Unemployment has remained stubbornly high even as the economy has grown an average of 5% a year over the past decade.

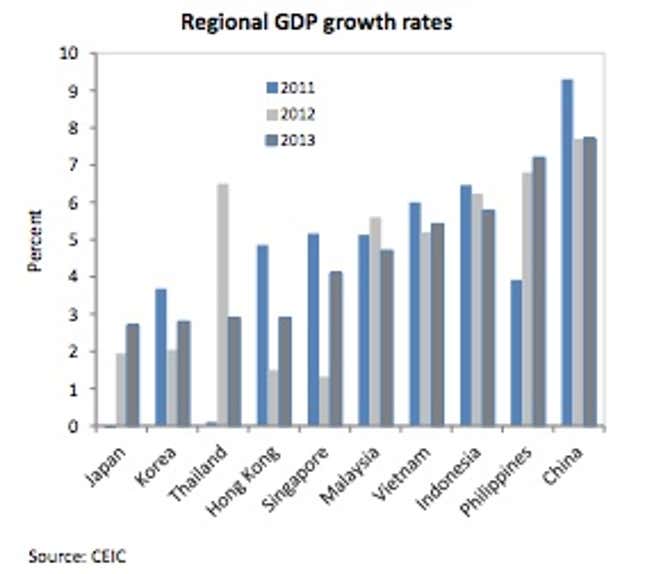

It’s only been over this last decade that the Philippines has entered a period of consistent growth—for much of the second half of the 20th century, its economy went through various booms and busts. And over the past year, the country has marked several firsts: an investment grade credit rating, hosting the World Economic Forum, and now a population of over 100 million.

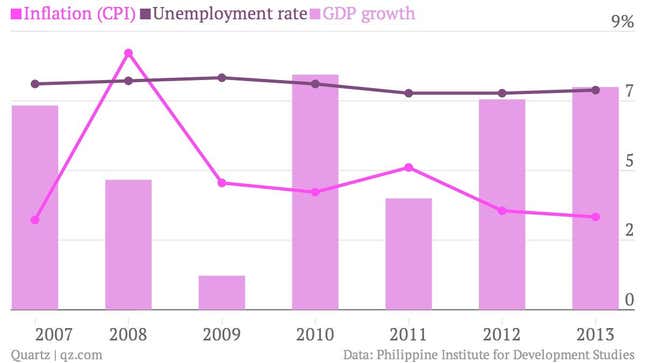

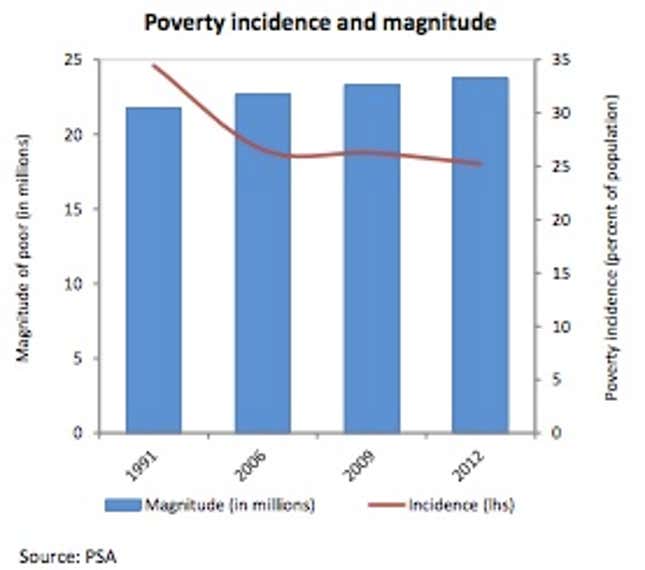

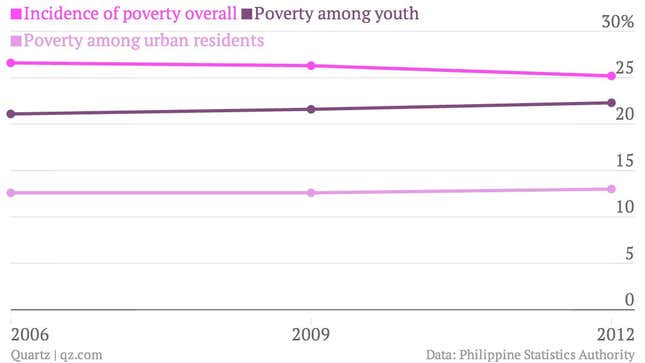

Those accomplishments are marred by troubles like inflation, which has more than doubled over the past year to 4.4%, making food costs and already high utility prices worse, squeezing middle class and poorer families. The country’s economic growth has mostly benefitted the top 20%, according to a recent World Bank report (pdf). Almost a quarter of the population lives beneath the poverty line, earning less than 16,841 pesos (about $386) a year. That figure has remained almost unchanged since 2006, despite the economy growing by 7.2% last year. In June, 12.1 million surveyed residents said they saw themselves as poor, compared to 11.5 million in March.

And although the percentage of Filipinos living in poverty has declined slightly over the last few years, is has actually increased among youth and urban residents—the two segments of the population that are growing the fastest.

Moreover, a larger labor force may not be good for unemployment, which is already around 7%, among the highest in Asia. Already, it’s estimated that between 2013 and 2016, around 1.15 million Filipinos will have entered the workforce a year, but only a fourth of them will find stable jobs, according to the World Bank. As much as 75% of workers are employed in the informal sector, which means they have no protection from job losses—a figure that’s likely to increase as the population surges.

The country’s dependency on remittances—money flowing into the country from around 10.5 million Filipino migrant workers living in the Middle East and elsewhere around the world—continues despite the government’s attempts to diversify the economy and encourage more workers to find employment at home. The Philippines was the third-highest recipient of migrant remittances (pdf) in 2013, after India and China, with remittances rising 7.4% from the year before. The country depends on these funds, which accounted for 8.4% of the country’s GDP last year, for foreign exchange and to drive domestic consumption.

The country’s seemingly endless political scandals are also affecting its growth prospects, with the International Monetary Fund revising its projections for the Philippines downward after the country’s Supreme Court declared parts of a government stimulus package illegal. The IMF expects growth of 6.2% this year, down from 7.2% last year. Poverty, inequality, and high unemployment or underemployment all make it difficult for the government to push domestic consumption.

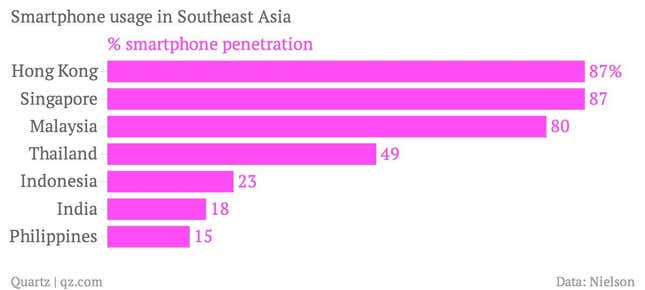

Currently, spending is driven mostly by low and medium-end services and remittances from abroad while the manufacturing and agricultural sectors have been shrinking. New industries are still nascent: internet penetration is only around 36%, and though mobile phone are ubiquitous, smartphone penetration is among the lowest in the region, at 15%.