Update (Nov. 7): German industrial production data came out, and they were considerably worse than expected: output was down 1.8% in September, compared with a Reuters consensus forecast of 0.5%. The EU has also cut its GDP growth forecast for Germany in 2013 to 0.8% from 1.7%, bringing down the whole euro-area forecast to a mere 0.1%. This makes the German manufacturers’ gamble described below even greater.

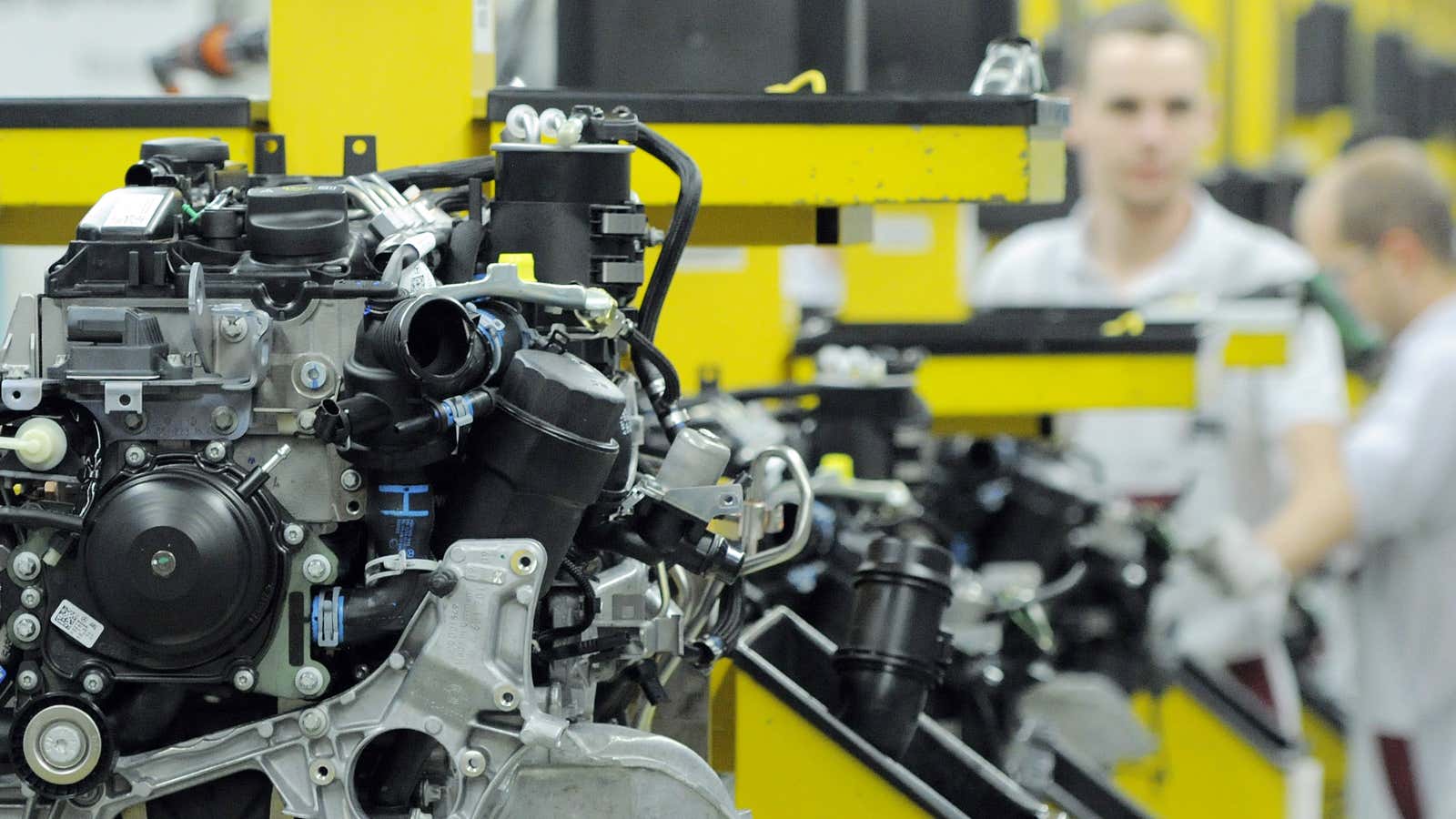

Original (Nov. 6) Tomorrow we’ll get our latest read on what is arguably Germany’s most crucial economic indicator: industrial production. All the signs appear to be pointing downwards, suggesting that Germany is, as my colleague Matt Phillips puts it, “having trouble staying out of the European vortex.” Auto manufacturing, Germany’s largest industry, has already begun to suffer from a dramatic decline in European car sales, with new car registrations falling 10.8% year-over-year across the eurozone and 10.9% in Germany. Other industries are showing weakness, too; according to data released Tuesday, consumer goods orders fell by 2.1% in September, suggesting that consumers are cutting spending on more than just cars.

But the long-drawn-out euro crisis has given big German businesses time to predict and account for a slowdown not just in southern Europe but ultimately in Germany itself. Behind the scenes, some of them are looking abroad to replace falling domestic and euro-area demand. BMW today reported a 9.0% rise in sales quarter-over-quarter, which it credited largely to strength in China and the US—its largest markets outside of Europe.

But with slowing growth in China, BMW—like some of its competitors—has expanded dramatically in other emerging markets, particularly Brazil. On October 20, BMW said that it was planning to build a €200 million ($261 million) plant in the prosperous Brazilian state of Santa Catarina, meant to help give the company access to Brazil’s car market. That plant is slated to open in 2014. That same week, Volkswagen said it would invest €3.4 billion from now through 2016 to expand its plants in Brazil. Similarly, German business software giant SAP said in May that it would spend more than $2.5 billion in China, the Middle East, and North Africa by 2015. In a note published last month, Citigroup analyst Walter Pritchard even said that the company could be considered “an under-appreciated play on emerging markets” because of its exposure there.

Meanwhile, Siemens—Germany’s largest company by asset value—has struggled, in part because it missed the boat on emerging markets, and is correspondingly more exposed to Europe than other big German firms. “Siemens Industry is cyclical, which creates downside risk to forecasts,” Deutsche Bank analyst Peter Reilly explained, advising investors not to increase their holding of the stock. Further, he wrote, “Siemens owns 50% of [Europe-centric] Nokia Siemens Networks and its financial performance has been consistently disappointing.”

It’s all part of an overarching strategy. Big German businesses are continuing to take advantage of the fact, being German, they still enjoy relatively low borrowing rates. They’ve taken this money to expand non-European businesses, particularly in Brazil and China, hoping that this will compensate for their stagnating returns in stagnating Europe in the long term.

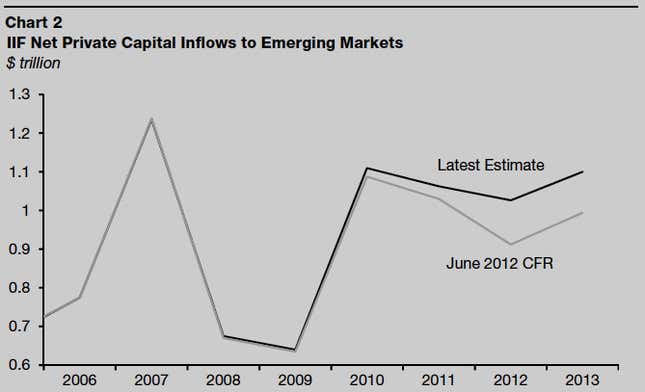

That’s all well and good, but it’s still a risky bet. Money has been pouring into emerging markets since early this year because the macroeconomic situation has been relatively calm—at least in comparison to last year. But those flows are liable to dry up if investors get cold feet about the global economy and Europe falls deeper into crisis. That was certainly the case last year, as the chart below demonstrates. Bottom line: advanced economies like the US and Europe still lead investment, and when investment dries up there it dries up everywhere. Just how much is anybody’s guess.