Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s time as Turkey’s prime minister didn’t end as strongly as he would have liked. That’s despite a fairly comfortable victory in the country’s first direct presidential election yesterday.

Barred from another stint as premier by his party’s three-term limit, Erdogan ran for president instead: essentially, what Russia’s Vladimir Putin did in 2008, but in reverse. He plans to imbue the role—hitherto ceremonial, appointed by parliament—with more power. He starts his new job later this month.

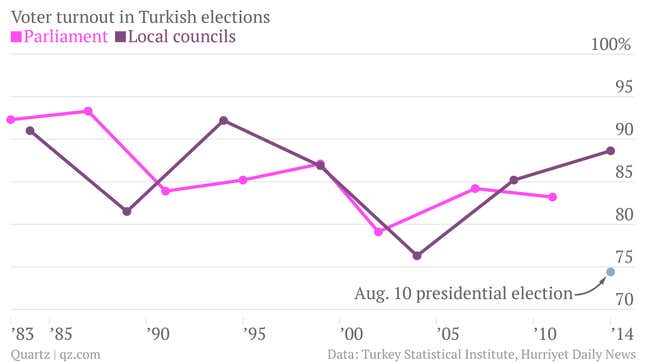

But Turkish voters didn’t turn up at the polls like they have before, muddying the mandate. Around 75% of Turks voted yesterday, down from nearly 90% in local elections earlier in the year. (Voting is compulsory in Turkey, but punishments are rarely enforced.) In fact, the inaugural presidential election saw the lowest voter turnout in Turkey in decades:

The markets also voted on five more years of Erdogan, in a matter of speaking. Turkish stocks opened strongly today, with investors apparently calmed by the continuation of something resembling the status quo. But as the day went on, and the reality of the uncharted political waters that Erdogan’s switch to president entails sank in, Turkish stocks and the lira fell:

Erdogan’s opponents say that his authoritarian streak, manifested in the intimidation of journalists, and crackdown on social media, has intensified since a huge corruption row engulfed the highest levels of Turkish politics last year.

“Overall, Erdogan’s rise to the presidency will have negative implications for business and investors in Turkey but this is likely to manifest itself gradually over time,” says Wolfango Piccoli, managing director at research firm Teneo Intelligence. “The policy-making process is expected to become more opaque and unpredictable, and the system of checks-and-balances could be further weakened.”

But the people have spoken, and Turkey will get five more years of “Erdagonomics.” This is what that has looked like over the soon-to-be president’s 11-year stint as prime minister…

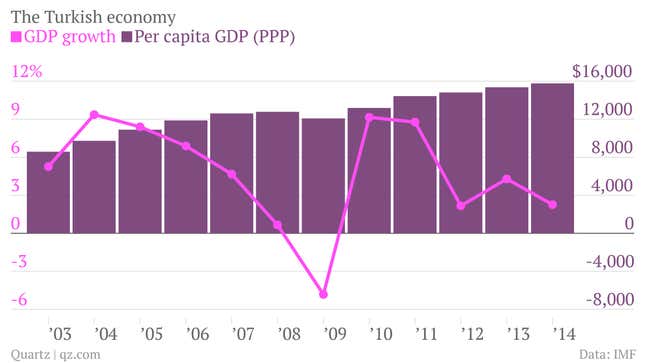

Per capita incomes have risen steadily, although economic growth is subject to wild swings. Moody’s dubs this the “volatility that has long characterized Turkey’s growth model”:

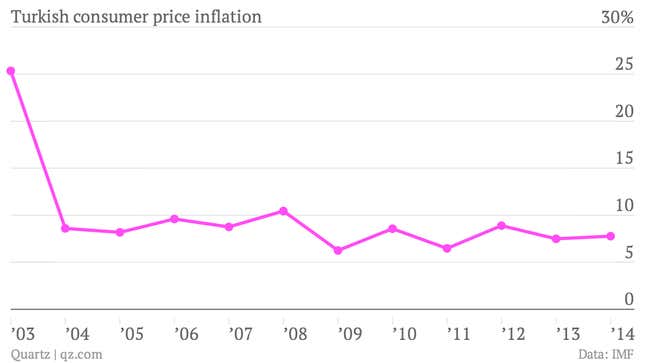

Inflation has been reined in under Erdogan’s watch, but still consistently comes in above official targets (currently 5%):

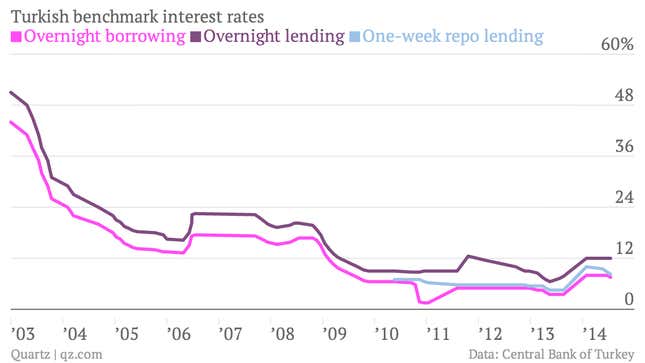

Under pressure from the government, Turkey’s central bank has been fighting to remain independent, with mixed success. Frequent changes—up and down—in the country’s complex array of policy rates has often caught financial markets off-guard:

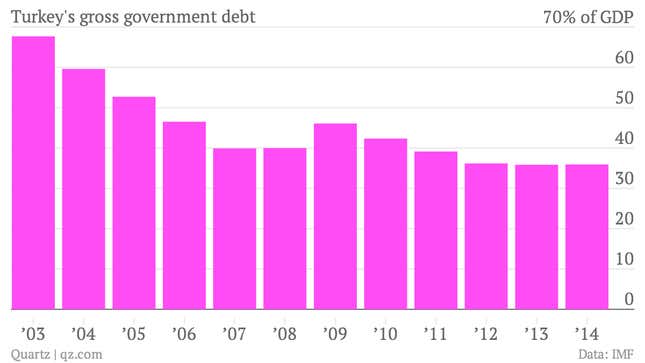

The government deficit is manageable and its debt burden is relatively low…

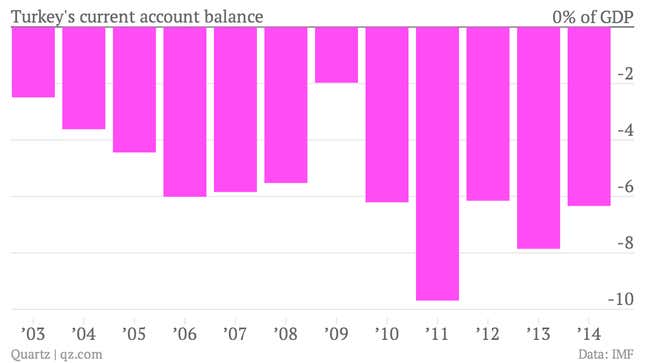

…But Turkey’s overall debts are disproportionately owed to foreign creditors, a point of weakness amid lira volatility. The country’s large current account deficit, a broad measure of its reliance on imports and transfers from abroad, earned it a spot in a group of emerging-market countries dubbed the “fragile five”: