It’s the latest Wall Street fad. No, not Gucci loafers or flashy Maseratis: corporate tax inversions.

So-called tax inversions are essentially a way for big US companies to avoid the tax man, by shifting their tax liabilities from the US to countries with much cheaper corporate tax rates. The Chicago-based drug maker AbbVie’s planned $54-billion acquisition of its Ireland-based rival, Shire, is a good example of that trend.

Credit Suisse estimates that tax inversions represent 6% of overall global merger and acquisition activity–a trend that has clearly been growing, as this chart indicates:

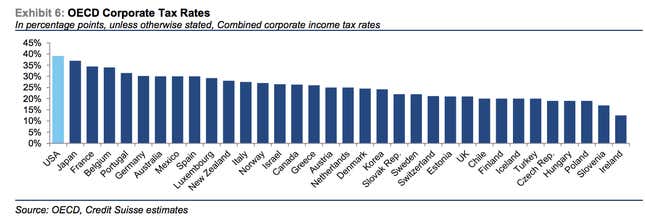

The 35% corporate tax rate that the US imposes, relatively high compared to other countries, is the main reason inversions have become so popular of late. Here’s how the US’s rate stacks up against those of other countries.

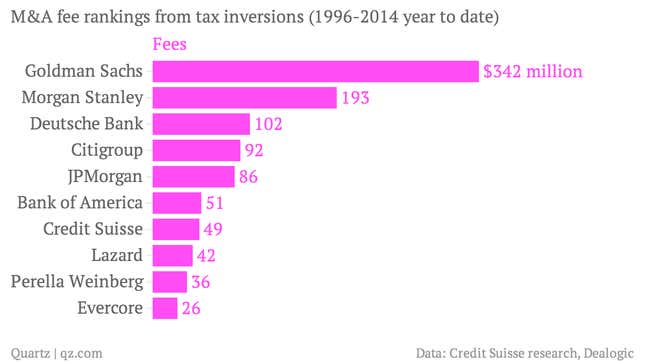

All this tax finagling has been a big boon for Wall Street banks, which collect fees by advising clients on mergers and acquisitions. Perhaps it’s no surprise that one of the biggest M&A advisors, Goldman Sachs, has been the top inversion dealmaker, with some $342 million in fees from tax inversions from 1996 to 2014, according to research compiled by Credit Suisse. (It’s worth noting that tax inversions represent 1% of the nearly $32 billion in fees Goldman has collected for arranging M&A transactions over that period, according to Dealogic.)

As one might imagine, US president Barack Obama isn’t thrilled about tax inversions, and has suggested that action may be taken to hamstring corporations’ tax sidestepping. Recently, Goldman research analyst Alec Phillips issued a client note highlighting a few ways the government might do this:

“Earnings stripping.” The relatively high US statutory tax rate creates an incentive for companies to deduct as large a share of expenses as possible from US income. One means of doing so involves deducting interest in the US on loans from foreign subsidiaries. Rules exist to limit this practice, but the Treasury appears to be looking at tightening these rules. Rep. Levin’s draft legislation would also further restrict these strategies.

Treatment of deferred overseas earnings. US-based companies typically avoid repatriating foreign profits in order to defer US tax on those earnings. The downside of doing so is that it is difficult under existing rules to distribute those earnings to shareholders or invest in US operations. Tax inversions provide companies with much greater flexibility in this area and this is a primary motivation for some companies to expatriate. Shay proposes tightening rules on use of pre-inversion foreign earnings, as does Rep. Levin’s draft legislation. However, while nothing can be ruled out, future post-inversion foreign profits do not appear to be a focus.

So is the tax inversion golden goose cooked? Mergers and acquisitions have buoyed the revenues of investment banks like Goldman lately, so any threat to M&A could prove a serious damper on bank quarterly results. But it’s probably a safe bet that Goldman and its ilk will devise fresh ways to grease the M&A wheels.