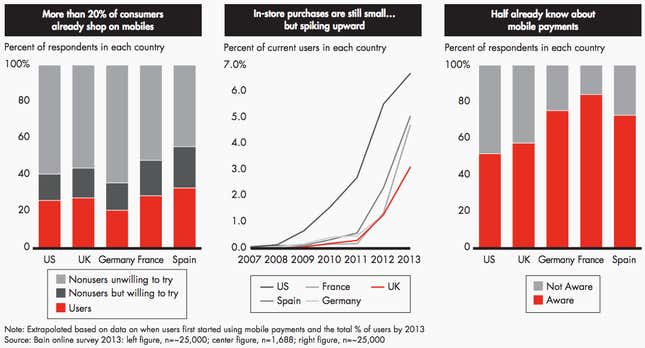

Despite a lot of investment and even more hype, mobile payments haven’t really taken off. While the idea of using a mobile phone or other device to quickly and securely pay for things sounds appealing, only between 3% and 7% of consumers in the US and Europe use their phones to buy coffee, books, or other physical goods in stores, according to Bain (pdf).

Why? The system is still a mess. In the US, for example, no in-store mobile-payments system has reached critical mass—thanks to a complicated set of relationships between merchants, card companies, payment processors, mobile operators, handset makers, and mobile-wallet providers. Companies are so focused on claiming their share of the “value chain” that they’ve lost sight of the needs of the people who are actually supposed to be using these services. Payment providers have done such a lousy job with their early mobile products that Starbucks has emerged as a leader by simply doing its own thing.

Now Apple, which will reportedly announce its mobile payment system next week, has a chance to kickstart the market. And it might actually succeed. Because of its size, power, and—most importantly—its focus on the user, Apple is uniquely positioned to make in-store mobile payments work. Finally.

Critical mass

Apple could start by creating the first simple, global brand for mobile payments. Whether it’s called iPay, AirPay, or something else, Apple could start by making something people will recognize. Apple is reportedly going straight to the source, forging partnerships with MasterCard, Visa, and American Express, so there shouldn’t be any question of whether people can link the payment cards they’re already comfortable using.

Apple, unlike Google, has absolute control over what goes into its phones, so it can ensure that all new iPhones—and other devices, such as its reportedly forthcoming wearable gadget—support its payment system. With more than 40% of the US smartphone market, Apple can get this service into millions of pockets faster than any other company. And because Apple insists on having the upper hand in its relationships with mobile operators, it shouldn’t have any embarrassing situations like Google had with Verizon Wireless, which effectively blocked Google Wallet in 2011.

Apple’s large and successful developer program means it can usually get merchants—large and small—to support new features. For example, it’s easy to imagine Apple offering a new rewards platform for its payments system, or creating ways for merchants to link their existing rewards programs, as it did with its Passbook app that launched in 2012.

Cachet and trust

Let’s face it, Apple has a unique ability among electronics brands to attract attention. Bain says that for a quarter of people who would consider using their mobiles for purchases, “novelty is reason enough to try it.” While not everything Apple touches turns gold—such as its failed social network, Ping—it has a good chance of getting people to at least try its payment system.

And some 800 million people—iTunes account holders—already trust Apple with their payment information. In an era where retailers’ databases seem to be compromised every week, with the right security features—such as potentially requiring a fingerprint scan to pay—Apple could foster the sense that its payment system is safer than swiping plastic. And also that it’s more private than a similar wallet run by Google, which is known to feast on all available data.

The right business model

Apple also has a clear, hardware-sales-based business model that allows for long-term thinking around user experience and privacy.

Apple makes the vast majority of its profit by selling iPhones, iPads, and Macs. If its payment system becomes popular, it will sell more iPhones, iPads, and Macs. (And, perhaps, iWatches.) If it becomes something people don’t want to live without, it will keep people loyal—and buying even more hardware. Apple’s iTunes store—including the App Store—is now an almost $20 billion annual business, and is probably profitable. For years, Apple said it aimed to run iTunes near break-even to support its hardware business. This could be a similar story.

While Apple certainly will enjoy having more control over payments, and may even demand a cut of each transfer, it does not need its payment service to generate any massive immediate revenue or profit, nor drastic disruption. Nor does it need to create any new, invasive businesses selling its payment data to merchants or advertisers. If anything, Apple should use this to its advantage.

The right time

Timing is also in Apple’s favor. Smartphones are now mainstream, a part of normal daily life. Payment processors have had time to build mobile support into enough point-of-sale systems that Apple could have decent take-up from the beginning. And more than half of consumers are already aware of mobile payments, according to Bain’s study—even higher outside the US:

Can Apple make mobile payments mainstream? We’ll likely learn more on Sept. 9, when Apple is expected to unveil its new system.