When Facebook executives meet potential advertisers, their biggest selling point is that the company knows whom it’s advertising to. In contrast to the wilds of the web, the proposition goes, Facebook users sign in to the service and make themselves known. Match their data with third parties—data brokers who provide loyalty card spending, for instance—and you have a fairly good idea of whether your ad has been effective. If user x saw ad y and made a purchase, there’s the return on investment. (Facebook stresses that these data are anonymised and the data are analysed only in aggregate.)

Most Facebook users are aware of this—or at least the bit about the service being tied to advertising. But Facebook’s tentacles reach far beyond its homepage. Its ”like” button is splashed across the web. Last month, the company suggested that advertisers include a Facebook tracking pixel on their sites to better measure whether the ads are working.

The notion that the world outside its homepage remains anonymous is increasingly untrue. Millions of internet users voluntarily give Facebook, Google, and others access to their movements across the web and on mobile when they use “social log in,” or the ability to sign in to a website using credentials from the big identity providers.

The web’s rent-a-cops—or emperors

Think about this way: In the early 1990s, people travelled around the web at will, only having to show their ID when accessing something important and personal, such as email accounts or while shopping, much as you would at the post office or in a shop. But soon the fetish for ID grew. By the late 2000s, somebody was asking for your ID every block of the internet you travelled, every street you crossed, every building you entered. Worse, each one of them issued their own credentials.

People eventually got sick of carrying a headful of IDs (usernames and passwords) around every time they want for a little stroll online; so in 2008 (pdf) Facebook and Google said to the others, “Look, let us be your gatekeepers. We can check people’s credentials and let them in for you.” Your Facebook or Google accounts suddenly became passports, giving access to all territories. In return for their service, these identity providers note the details of your comings and goings. It’s like if your government monitored where your passport was and sent you restaurant recommendations. (That day will probably come.) Or, to mix metaphors entirely, Facebook and Google exert suzerainty over the smaller websites that use their service.

The battle for your identity

The data that identity providers gather is a crucial component of their business. It is a useful thing to know what your users are up to when they’re on your site. To know what their movements are on the rest of the web is a bigger prize yet. And as mobile phones and tablets render old tracking mechanisms, such as cookies, increasingly ineffectual, identity is becoming the single most important tool to follow web users across multiple devices. The mission of every large web advertising firm is to be able to paint a complete portrait of their users.

As mobile has risen and this realisation has sunk in, the competition around identity has intensified. In 2012, Google started forcing new users to register for a Google+ account (something it finally stopped doing this week) and began integrating Google+ across its services. It ensures that people are always logged into its services. Meanwhile, Facebook has introduced a version of social login in which users can sign into third-party apps “anonymously,” which isn’t really anonymous at all.

Yahoo is also trying to regain lost share; it decided in May to stop accepting outside credentials for its Yahoo Sports Tourney Pick’Em, a college basketball-themed service. The change will gradually roll out across all of Yahoo’s services. Mobile networks are furious at being left behind and want to get back in on the action. Governments are getting into the act too.

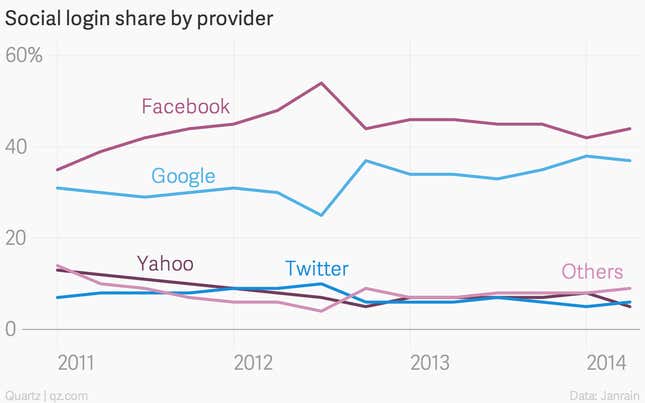

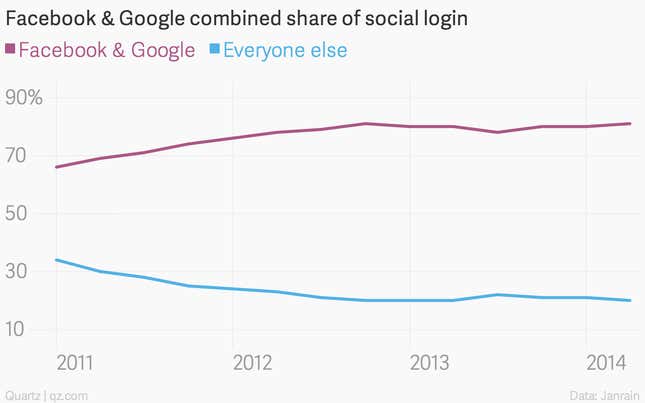

Between them, Facebook and Google account for over 80% of social log-ins, according to Janrain, a company that helps manage social login integration. The gap between the two and everybody else is gradually widening.

Give the people what they want

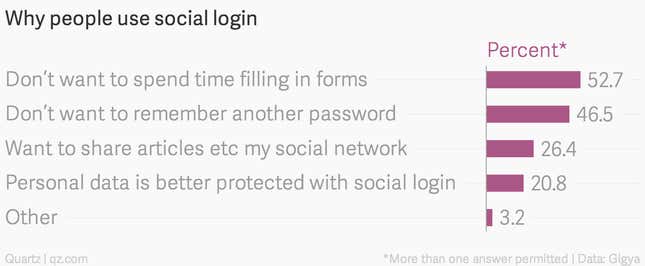

Consumers seem happy about this state of affairs; they have been driven into the arms of big identity providers by the sheer volume of passwords they are expected to remember as they travel the web. Gigya, another social identity company, surveyed 2,000 American men and women and found that some 77% of respondents had logged into a website or mobile app using a social network account at least once. That’s a big rise from 53% last year.

Of the people who have used social login, a third said they use it whenever it is available. The top two reasons were the time it takes to register on sites, and the hassle of remembering yet another username and password.

It’s clear why websites and apps use social login. Some 60% of respondents said they had abandoned a purchase on a website or mobile app because it required filling out an online registration form. And nearly two-thirds of respondents said they were likely to use social login on their phones instead of creating a new username of password, suggesting convenience is what drives use. Indeed some enterprising programmers are trying to make the process of social login even easier than it already is, integrating social login in the background.

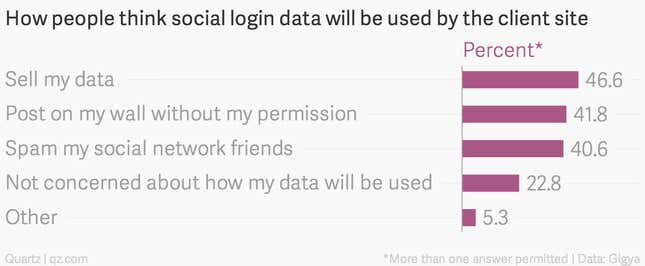

And it’s not like people aren’t aware of what signing in with their social media accounts actually means.

That suggests internet users have come to accept the trade-offs they must make for convenience. It suits everyone: identity providers, which get their hands on more data; third-party websites that can make life easier for their users; and regular people, who now have to remember fewer passwords. But it also means handing ever more to some of the richest and most powerful companies on the internet.