The future of passwords really is no passwords

The Wall Street Journal’s tech columnist (and until recently my colleague here at Quartz), Christopher Mims, yesterday handed out his Twitter password (paywall) to the Journal’s millions of readers. ”Knowing that won’t help you hack it,” Mims wrote, since he uses two-factor authentication, an added layer of security offered by the big web firms. With two-factor authentication, Twitter sends a code to your mobile phone, which you need to enter on the site in addition to your password.

The Wall Street Journal’s tech columnist (and until recently my colleague here at Quartz), Christopher Mims, yesterday handed out his Twitter password (paywall) to the Journal’s millions of readers. ”Knowing that won’t help you hack it,” Mims wrote, since he uses two-factor authentication, an added layer of security offered by the big web firms. With two-factor authentication, Twitter sends a code to your mobile phone, which you need to enter on the site in addition to your password.

Unsurprisingly, Mims was deluged with codes as online pranksters made, by his reckoning, some 200 attempts to gain access to his account.

It was not a bright move. Nor is two-factor authentication the future of passwords (though it is certainly welcome as extra security). Three out of four people in the US, the UK, Brazil and Russia don’t know what two-factor authentication is, let alone use it. Instead, the people who spend their days thinking about making passwords easier think about how to get rid of them entirely, rather than how to add more layers of complexity for famously lazy users.

You’ve got mail

“Sign-in is the part of the site of the site no one cares about. It’s not a feature; it’s a necessary evil. So the question is how do we make that as painless as possible,” says Blaine Cook, formerly of Twitter and now a co-founder of Poetica, a collaborative-writing tool.

It is worth thinking about what exactly a password proves, Cook says. When you forget your password, as you inevitably will, any web service will send you an email for you to reset it. All a password boils down to is being able to prove that you have access to your stated email account. Why not cut out the middleman?

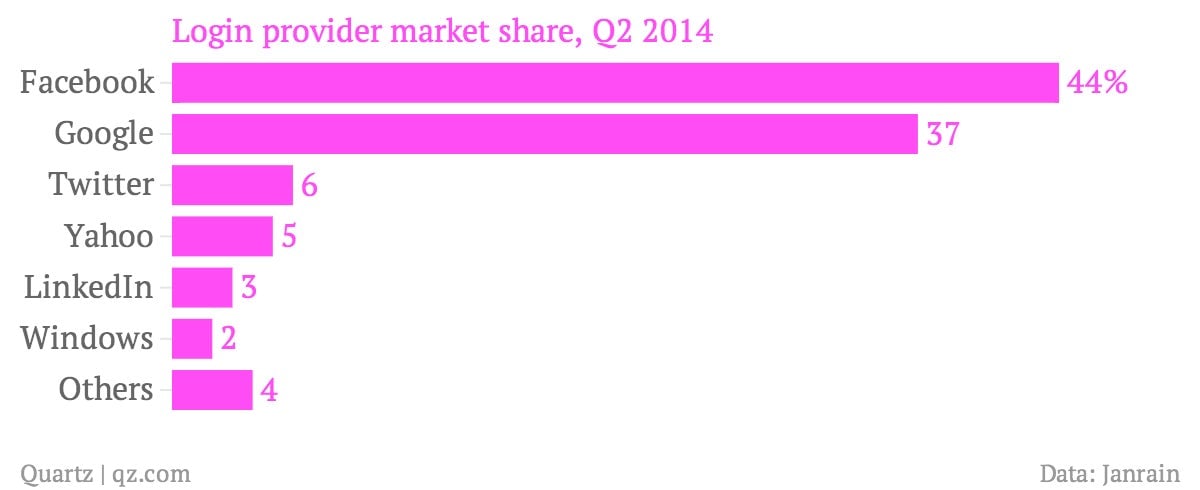

It is not a new idea. According to Janrain, which helps some 400,000 websites manage login, 90% of American internet users have encountered a social login (such as “Sign in with Facebook”) and more than half of them use it.

But Cook’s way of doing it is different: Rather than remind users that they have to sign in, Poetica removes the the ugly bits. The first time a user visits Poetica after the initial registration, all she has to do is enter her email address. Since people tend to be logged in to their Gmail or Facebook accounts in any case, the system checks to confirm their logged-in identity on those services and then lets them in. “We can do that without prompting for a password, or any user intervention at all, in most cases for existing users,” Cook says.

What about people who are naturally suspicious of anything that connects them to the big data hunter-gatherers of our age? Cook says people connect their email to their third-party accounts when they enter their email addresses to sign up, even if they don’t necessarily think of it that way. And as Tim Bray, formerly of Google’s identity department and an internet pioneer, says that your big internet firms might be better at protecting your data from the government than little ones: ”While big internet companies are prime targets for snoopy public servants, we’re also pretty well lawyered-up, compared to the vast majority of sites and apps up there.”

Moreover, Cook says he is working on supporting third-party email providers through open-identification standards. Another idea he has is to send people an email with a one-time login that installs a cookie on users’ machines. That keeps them logged in. If they sign out, they can request another one-time login. But in the end, it all boils down to email, rather than yet another password for people to remember—or forget.

A key for your online locks

The other idea in the works comes from Google. The internet giant is experimenting with a physical login device that does away with passwords. Employees at Google now use a USB key that, when plugged in, authenticates that it really is them. Googlers who use the device say that it is the future (well, they would.)

There are signs that Google may be bringing physical authentication to consumers. One of the features Google played up at its recent I/O developer conference was the ability for an Android phone to unlock itself if it detects the presence of a paired Android bluetooth device belonging to the same owner, such as a smartwatch. It is the same principle as two-factor authentication—it relies on the user having a physical device on her person—but without the added complication of receiving and entering in a code.

That is likely only the first step. As our devices grow ever more connected, and as login requirements proliferate, expect the password to die and other second- and third-factor forms of authentication to rise—but it will be smarter and more seamless, rather than something that makes the process more cumbersome for users.