It’s exhausting, being a walrus. Seals can swim indefinitely. Not walruses. After a day cruising Arctic water for food, they like to plant their tusks onto an ice floe, haul their blubbery selves up, and have a snooze. But it’s been hard to find a comfy chunk of sea ice this summer. So walruses are opting for the next best thing: Alaska.

An estimated 35,000 have overrun the coast north of Point Lay, in northwest Alaska, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

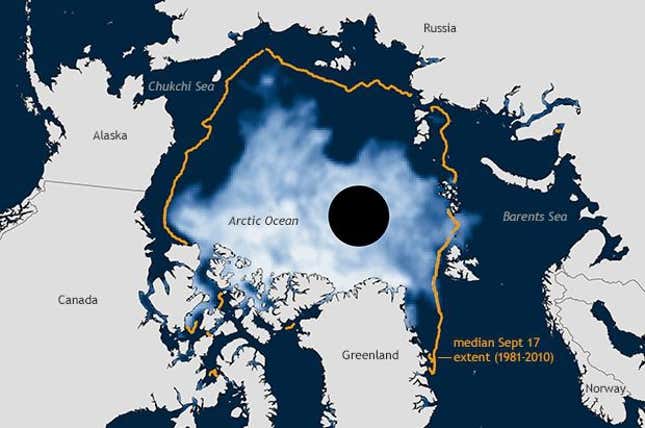

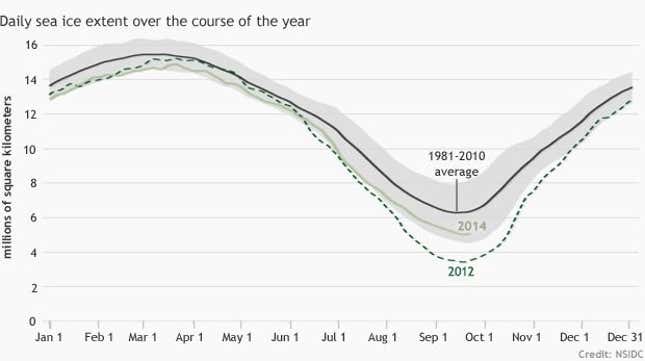

Walruses in the Bering Sea use ice floes as floating home bases between dives to the sea bottom, where they snack on clams and other mollusks. In the winter, that’s no problem. And until recently, it wasn’t an issue in summer, either. Normally, female walruses and their young follow the sea ice north into the relatively shallow Chukchi Sea, just north of the Bering Strait, where diving to the bottom is easy. But as summer temperatures rise, the Arctic sea ice has shrunk, receding further and further north, and pulling the ice mass into swaths of the Arctic Ocean as many as two miles deep.

Since walruses can’t hunt easily in those waters, they have to find a new home base for summer foraging, scientists suspect—and that’s why the animals are heading to Alaska. This isn’t the first time walruses have been found summering there; they’ve also shown up in large numbers in 2007, 2009, and 2011, when some 30,000 of them camped out on a 1-kilometer stretch of Point Lay.

As it happens, the chunk of sea ice that caps the Arctic was, this year, the sixth-smallest on record.

“The walruses are telling us what the polar bears have told us and what many indigenous people have told us in the high Arctic,” Margaret Williams, managing director of the World Wildlife Fund’s Arctic program, told the AP, “and that is that the Arctic environment is changing extremely rapidly and it is time for the rest of the world to take notice and also to take action to address the root causes of climate change.”