In the three decades since Kailash Satyarthi—who has just been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize with Pakistan’s Malala Yousafzai—began work as an activist, the number of underage Indian children being exploited for labor has fallen, even as the risks faced by minor girls in the subcontinent has worsened.

The 1980s, when Satyarthi founded his child rights organisation, Bachpan Bachao Andolan, was the worst decade for Indian children in recent times. Over 13.5 million children between 5 and 14 years were at work. By 2011, according to India’s Census, that number has fallen to under 5 million.

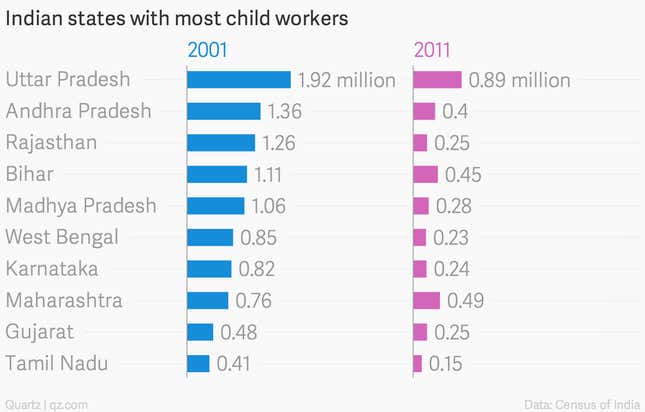

Still, widespread exploitation of child labor persists across India, particularly in northern and western states of the country. The 10 states with the highest number of child workers (table below) in 2011 are exactly the same as those in 2001, only the magnitude of the problem has changed.

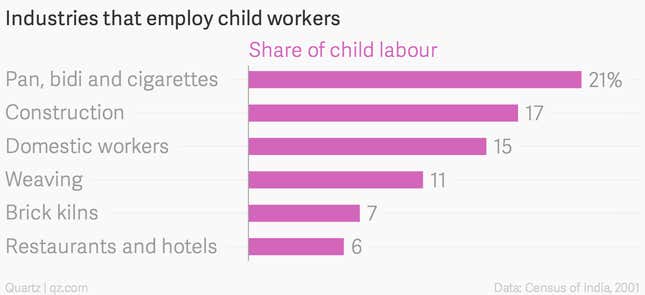

Often, these children—overworked and underpaid—are employed in sectors where the risks of physical and long-term medical harm are substantial. India’s tobacco and construction industries, according to the 2001 Census, are two of the biggest employers of children.

Many of these children are forced into such work through a wide network of formal and informal “placement agencies,” said a report by the Global March Against Child Labour, where Satyarthi is a founder and chairman. The report estimates that between $35 million and $360 billion is generated through the exploitation of children in India.

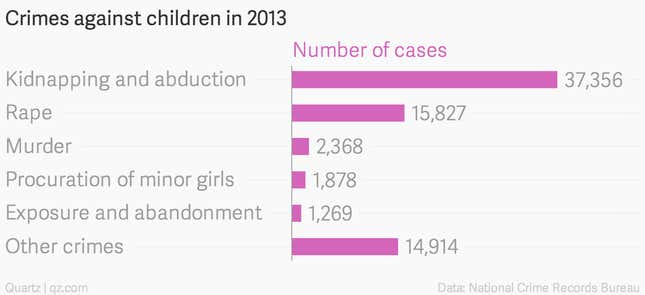

The most recent numbers from India’s crime registry also reveal that the most prevalent crime against children is kidnapping and abduction—more than double the number of rapes, or other crimes reported in the country.

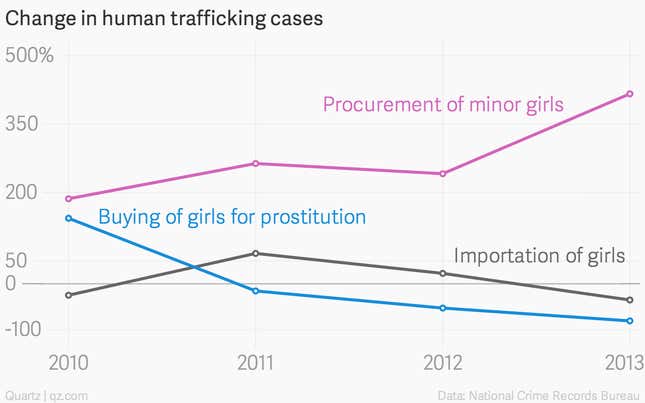

While India’s children remain vulnerable as a whole, it is minor girls who face the greatest risks. In the last few years, the cases of procurement of minor girls—presumably for domestic work and prostitution—has risen significantly, even as there has been a decline in other related human trafficking incidents.

And even those who make it through their early years—like 14-year-old Raj Kumar, a bookstore helper at Delhi’s Janpath—are often failed by India’s ramshackle education system. Kumar left school after finishing his eighth grade, though over 40% of Indian students drop out (pdf) even before reaching that point. “I didn’t feel like studying,” he tells Quartz, ”Studies don’t interest me.”

Instead, Kumar joined his family business that manufactures knives, which he had to quit after sustaining repeated injuries. Now, the scrawny young man with neatly parted black hair spends most days helping arranging books.

“I don’t know what a Nobel Prize is,” he says. “I don’t know who Malala is.”

Staring down from a shelf next to him is Yousafzai’s bestselling 2013 autobiography, I Am Malala: The Girl Who Stood Up for Education and Was Shot by the Taliban.