The chef Jiro Ono has delivered a grim warning. (Yes, that Jiro—the eponymous sushi guru in the hit 2011 documentary Jiro Dreams of Sushi.) “I told my young men three years ago sushi materials will totally change in five years,” he said, quoted in the New York Daily News. “And now, such a trend is becoming a reality little by little.”

Ono owns Sukiyabashi Jiro, a 10-seater in downtown Tokyo that boasts three Michelin stars and is reputed to be the world’s best sushi restaurant. (The base price for a 20-piece set sushi meal is ¥30,000, about $262.)

Of special concern is tuna, said the 89-year-old Ono in a recent talk with his eldest son, Yoshikazu, at Japan’s Foreign Correspondents Club. And in particular, bluefin tuna—whose fatty belly meat turns up on fancy sushi menus as toro. That’s the species so prized that a prime specimen sold for $1.8 million in Tokyo’s Tsukiji fish market in 2013. The scarcity of high-quality Pacific bluefin tuna has left Japanese fishmongers sourcing from the Atlantic. Even as Japan’s fishing fleet lands less than its quota for lower-quality tuna stocks, it consistently catches its entire quota of precious Atlantic bluefin.

“I can’t imagine at all that sushi in the future will be made of the same materials we use today,” the elder Ono said. His son adds that sushi’s growing popularity worldwide had led to a surge in demand for bluefin tuna, leaving Japan’s sushi-makers increasingly dependent on farmed tuna.

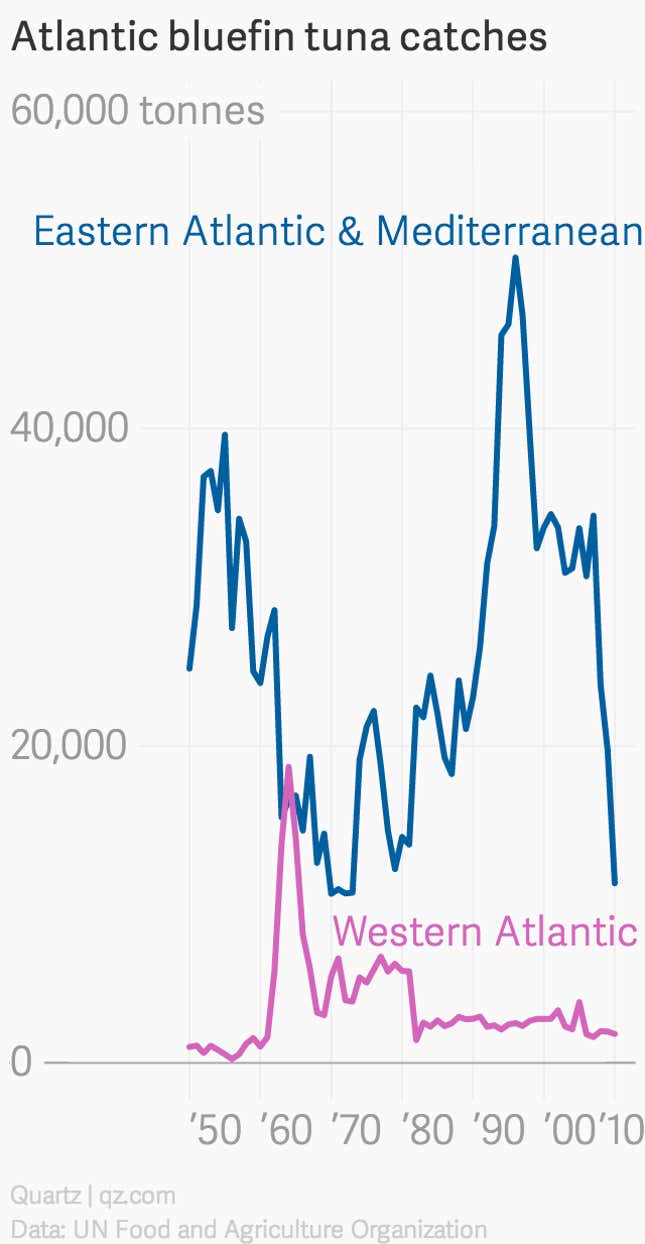

Atlantic bluefin stocks are indeed in peril. That’s partly because regulators have allowed fleets to catch too many tuna for the species to rebuild its stocks.

The western bluefin population is now less than half of what it was in 1970 (and the population had already been heavily fished for decades at that point). On the other side, in the eastern Atlantic and Mediterranean Sea, after hitting a historic low in 2010, the bluefin population are now thought to be on the way to recovery, according to the latest estimate. That’s likely due to the fact that since 2007, when a rebuilding plan began, the regulator has reduced the allowable limit by 82%; it slashed the western Atlantic catch limit by only 37%.

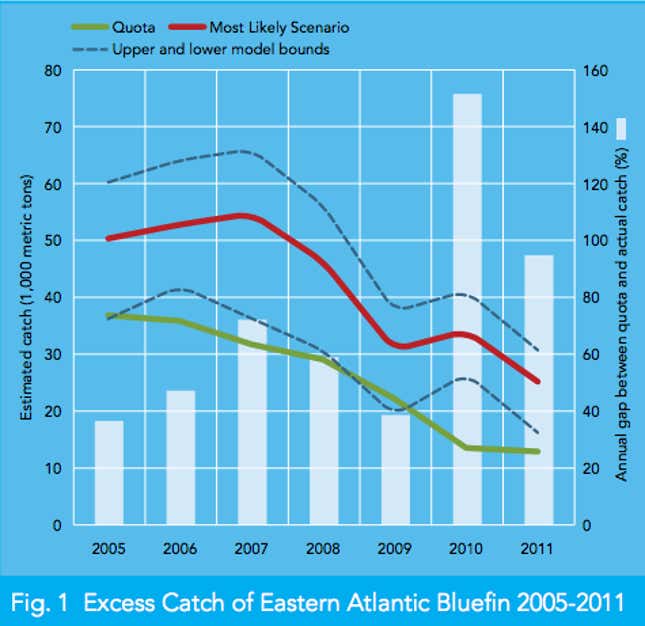

Another big factor, however, is rampant illegal bluefin fishing. The high prices bluefin fetch encourage fishermen to catch more than their countries are reporting, making it easy to overestimate stock size. Worse, blackmarket tuna fishermen often catch juvenile fish, making it even harder for the species to recover.

And it’s not just tuna populations that are suffering. As Yoshikazu Ono notes, slow-maturing shellfish such as abalone and ark shell are also being harvested so fast their stocks are shrinking.

“They catch them all together (before some are ready),” he says, “pushing the stock to deplete.”