(Warning: This post contains a graphic image)

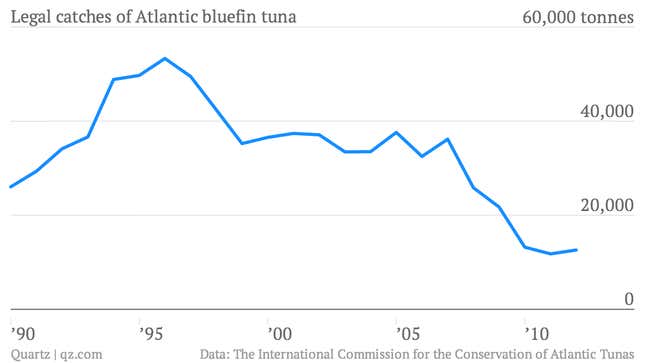

Atlantic bluefin tuna is tasty. So tasty, in fact, that the fish is also endangered. There are now only half the number of Atlantic bluefin tuna in the sea that there were in 1970. That’s despite rules set by governments around the world that have restricted tuna fishing, with the goal of leaving enough of them in the sea to reproduce faster than they’re being caught.

But the Atlantic bluefin tuna population refuses to bounce back—and it may be continuing to dwindle. Here’s one clue as to why: In the last year, authorities have seized at least 186 tonnes (205 tons) of illegally caught bluefin tuna in Italy, Spain and Tunisia, according to the Pew Charitable Trusts and MedReAct.org, a Mediterranean-focused conservation group.

In other words, fishermen are catching way more tuna than they’re supposed to. That’s making it near-impossible for regulators to revive the Atlantic bluefin tuna population, which is bad news for conservationists and also threatens the legal fishing business, says Pew’s Amanda Nickson.

So valuable is this fish—it’s the optimal species for the prized delicacy of fatty tuna sushi (a.k.a. toro or maguro)—that fishermen will go to great lengths to catch them, the report reveals. For instance, one operation that Italian authorities busted in March was smuggling nearly 38 tonnes of illegal tuna (link in Italian), worth €300,000 ($402,000).

Of course, 186 tonnes is only a fraction of the 7,939 tonnes of Atlantic bluefin tuna that the EU allows its fishermen to catch each year. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg; the volume of illegal catches is probably far higher.

Some simple math offers a glimpse of the probable scale of the problem: Italian vessels alone accounted for 130 tonnes of the confiscated fish, but it stands to reason that Italian fishermen are not the only ones catching bluefins illegally. Given that in 2012, Italy’s legal haul totaled around 15% of the world’s legally caught Atlantic bluefin tuna, it’s likely that, when contraband fishing by other countries is included, the number of Atlantic bluefin tuna being caught around the world each year is many times that amount.

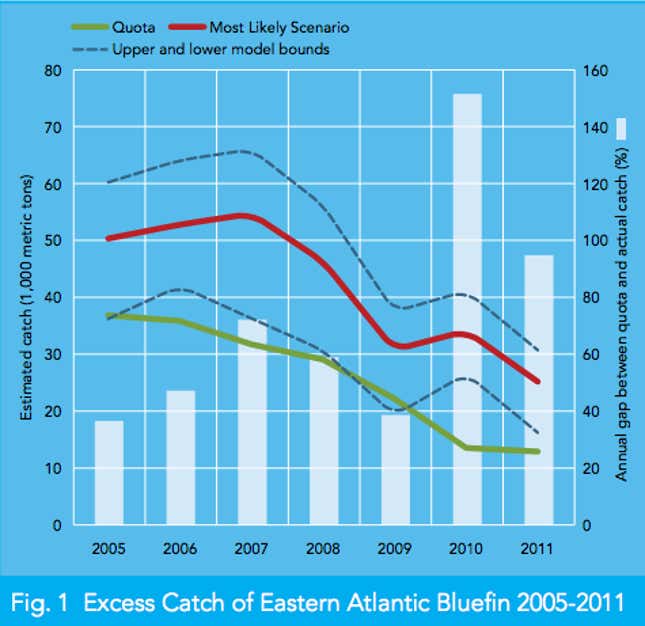

Here’s how Pew estimated the trend in illegal catches as of 2011:

The weight of the illegally caught tuna tells only a part of the story. To make matters worse, the age of fish caught is an equally important factor in rebuilding fish stocks, and the illegal fishing seems to be particularly hard on small baby fish—making it even harder for the species to recover. Bluefin tuna can live as long as 40 years, meaning they can reproduce a lot if given the chance. They also get huge—while a 20-year-old averages 8.7 feet (2.7 meters) long and can weigh 400 kilos, they can easily grow to 14 feet.

At least 8.2 tonnes of the seized tuna documented in the report were below the size limit (pdf, p.47)—many around 1 kilo (2.2 pounds), indicating that they were only four months old when caught. In late October of last year, for instance, the Sicilian coast guard seized five trucks carrying around 3,000 such baby tuna, according to the report.

What’s to be done? Track the catch better, for one thing. Pew recommends that the EU scrap its paper-based catch documentation system in favor of electronic tracking, which will help buyers ensure that their bluefin purchases were legally caught. After several years of delays, the electronic system is finally set to launch in March of 2015. Considering the volume of tuna that will be killed in the meantime, that’s too long to wait, says Pew.