How Alibaba is using bra sizes to predict online shopping habits

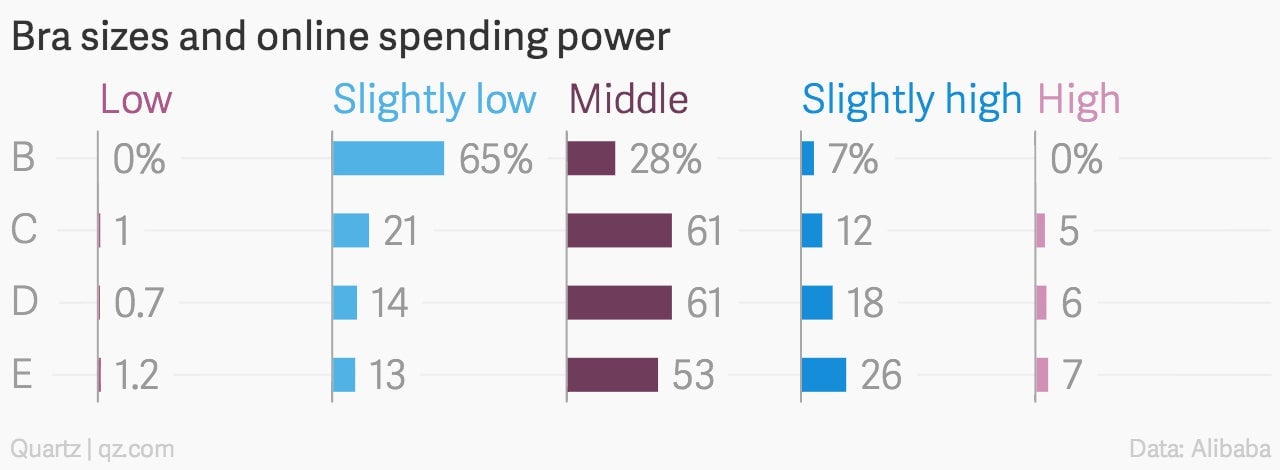

HANGZHOU—Earlier this summer, a group of data crunchers looking at underwear sales at Alibaba came across a curious trend: women who bought larger bra sizes also tended to spend more (link in Chinese). Dividing intimate-apparel shoppers into four categories of spending power, analysts at the e-commerce giant found that 65% of women of cup size B fell into the “low” spend category, while those of a size C or higher mostly fit into the “middle” or higher group:

HANGZHOU—Earlier this summer, a group of data crunchers looking at underwear sales at Alibaba came across a curious trend: women who bought larger bra sizes also tended to spend more (link in Chinese). Dividing intimate-apparel shoppers into four categories of spending power, analysts at the e-commerce giant found that 65% of women of cup size B fell into the “low” spend category, while those of a size C or higher mostly fit into the “middle” or higher group:

Besides the possible reasons for the trend— namely that younger women with less purchasing power may be the ones buying smaller-sized bras—the data nugget is an example of the kinds of detail the company gleans from the millions of orders placed daily on its e-commerce platforms.

Singles Day—the annual Nov 11 online shopping frenzy in which Alibaba saw as many as 2.85 million transactions a minute at its peak, and a total of $9.3 billion in sales—was both a test of, and a testament to, the company’s data-mining prowess. “We’ve only seen the tip of the iceberg. We really haven’t done even 5% of leveraging that data to really make our operations more efficient, consumers more satisfied,” vice president Joseph Tsai told Quartz at the company’s main campus in Hangzhou.

Throughout Singles Day, the company’s data team and operations managers watched and analyzed shopping volumes in order to communicate with merchants and logistical partners to keep supplies and deliveries going. The data is useful beyond yesterday’s event. Executives also kept an eye on how people paid for their goods, and whether they made their orders on their smartphones. Alibaba, criticized for being weaker on mobile platforms than its competitor Tencent, has been pushing its mobile platforms and has plans to take AliPay public eventually.

Alibaba, as well as Amazon and Japan’s Rakuten, are among the minority of less than 5% of e-commerce companies that use predictive data analytics, according to a 2013 report from the research firm Gartner. China, with its growing and still relatively under-researched middle class, is expected to be one of the world’s most important data markets.

Alibaba’s founder Jack Ma has named data mining as one of the company’s priorities, setting up a dedicated data platform of some 800 employees last year. At a conference in March, Ma said, “Six years ago we made our decision that Alibaba is going to be a data sharing company…We knew that society needs it. That is enough for us to take up the challenge of innovating cloud computing and big data technologies.”

According to Tsai, Alibaba’s trove of e-commerce data underpins its forays into seemingly disparate sectors from financial services and healthcare, to film, and soccer clubs—the company has already been using its data to build credit profiles for loans to individuals and businesses since 2010. “The next step is how to leverage the e-commerce data into adjacent fields,” Tsai said. “For example, if we have a lot of data on what people purchase in terms of food, groceries, as that data going to be helpful when we do healthcare? I think so.”

Alibaba’s rival JD.com booked over 14 million orders on Singles Day, using information on what shoppers are buying to make decisions on future inventory. “When you have a sale where you have 14 million data points in a single day, that’s going to be extremely helpful to your strategy,” Josh Gartner, senior director of international communications at JD.com, told Quartz.

But data can also befuddle. JD.com found that iPhone 5 sales during Singles Day were nine to 10 times higher than usual. Gartner isn’t sure why. In 2012, Alibaba was surprised to find bikini sales on Singles Day were the highest in the landlocked western region of Xinjiang. (Boyfriends and husbands were purchasing them as a way to promise their partners they would take them on vacation.)

For Alibaba, pushing into data and beyond e-commerce is already putting the company at odds with state-dominated sectors, like healthcare and financial services. Regulators announced limits on the amount of money that can be transferred from China’s state banks to Alibaba’s popular online money market fund Yu’e Bao, and blocked plans for a virtual credit card—perhaps to protect the state credit-card system, Union Pay.

“We don’t worry about that because these people really need to reform themselves, and we’re happy to be sort of a change agent.” Tsai said. “Dealing with regulations in China—you kind of make two steps of progress, but once in a while, you take a step back because the regulators may have different views about how fast they want to bring about change. What you think is reform, they think is disruption.”