Physarum polycephalum is a single-celled organism. All it consists of are microscopic batches of DNA, enzymes, and proteins. It joins up with other cells to form a giant single-celled mass, often found growing on sidewalks and by piles of decaying leaves—a sort of yellow goo. Its top speed is about 1mm an hour.

It is better known as plasmodial slime mold.

Yet this dumb slime can do all sorts of amazing and complex tasks, seemingly in spite of itself. Researchers found that when they placed the slime mold in a maze with four different paths; it found the fastest, most efficient way to find food in the maze every time.

Scientists placed oats in the shape of the towns around Tokyo—and the slime mold recreated the Tokyo rail network. It has also mimicked the national transport networks of Canada and Spain, as well as world shipping routes.

These feats took human beings centuries of political will, science, and engineering—and trial and error—to achieve. How can a organism with no brain and nervous system be as smart as us?

Here are a few of the organisational lessons that we can take away from physarum polycephalum:

1. Explore

The slime mold is single-minded in its goal to survive. To do that, it searches for food. This is the instinct by which the slime mold is able to replicate some of our much more complicated socioeconomic networks.

People, companies, and countries all have the same goal—to survive and thrive. The slime mold just gets itself to the same place much more efficiently.

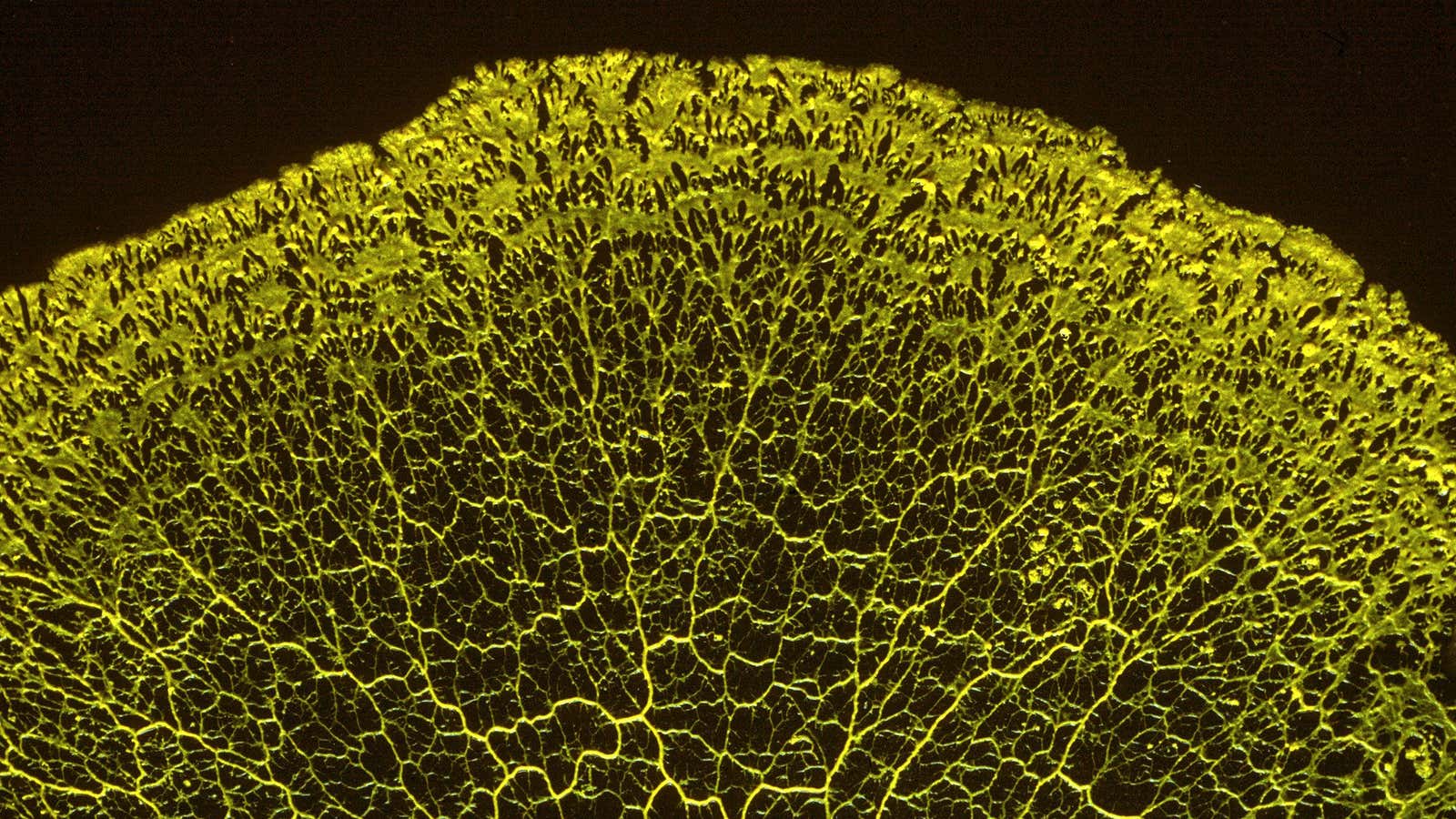

Heather Barnett is a multidisciplinary artist who lectures in art and science at London’s University of Westminster. She is fascinated by the slime. “It’s a beautiful organism,” she tells Quartz. “That fan pattern you see with the slime mold is entrenched in everything around us and within us.”

She says that the way the slime survives is by constantly being in a state of flux. “If it cannot find resources,” she says, “it will turn into a kind of scab or it will grow spores and get taken away by the winds to new lands.” Contrast this with ourselves. Human beings are very reluctant to change. But like the slime, every organization needs to realize when it’s time to give up and move on.

2. Remove hierarchies

Each cell of the slime mold is brainless. When they come together, there is no more or less order than there was before. ”If we strip away the layers of hierarchy and enable businesses to self-organize, if we remove control systems and create the conditions for interesting behaviours to emerge, could businesses become as responsive and adapative as the slime mold?” Barnett asks.

This is not a crazy concept. Valve, the video games developer, has no managers and every one of its 400 or so workers is considered more or less equal. Hirings and firings can both be initiated by hallway conversations and bonuses come from peer reviews. ”It’s a community of respect and the best idea wins no matter who it comes from, whether they’ve been at Valve for a year or founded Valve,” the company told the BBC.

Cristian Rennella, the co-founder of oMT, has written for Quartz on how the company set of guidelines and procedures (Google Docs with titles such as “Folder: Welcome. First month of work.”) to allow people to get ahead with no bosses and no meetings but still keep some sense of working towards a common objective.

That said, the quality of hiring is key. Not everyone is capable of working in a leaderless environment. This is all easier in small companies where there is a very clear sense of what is supposed to be done. But some of these “no-leadership” lessons can be applied to nimble teams within bigger organizations to help them get from A to B.

Barnett set up the Slime Mould Collective, which brings together writers, artists, architects, community activists, even management experts. The group deliberately takes on the characteristics of the slime mold: fluid structure, lots of communication, no system of control. “Hierarchy is something that is over-relied upon,” she tells Quartz. “The bigger it becomes, the more difficult it is to communicate and the usual solution is add more layers.”

3. Remember what you did wrong and tell someone

Scientists in Arizona wondered about the slime mold, trapped in a maze, could find the right path. ”Memory typically resides within the brain, but what if an organism has no brain?” they wondered. They showed that the slime has a kind of ”externalized spatial memory,” which it achieves by leaving a trail of extracellular slime where it has been. If it encounters the slime, it tries a different route.

Similarly, the workers in any slime-inspired company should try to recognize when they’re exploring a path that has previously led to failure. These feedback loops are key: the whole organization can benefit from one worker’s missteps. “The slime is looking for any opportunity,” Barnett says. “If it finds something, it can quickly communicate with the rest of the cells through a chemical reaction that it is has found something.”

If a brainless slime is so good at communicating, what excuse do we have?