“I’m lucky,” said Lokesh Kumar as he held up his left hand for examination. “I pulled out in time.” Half a centimetre of his thumb had been shaved off by a machine.

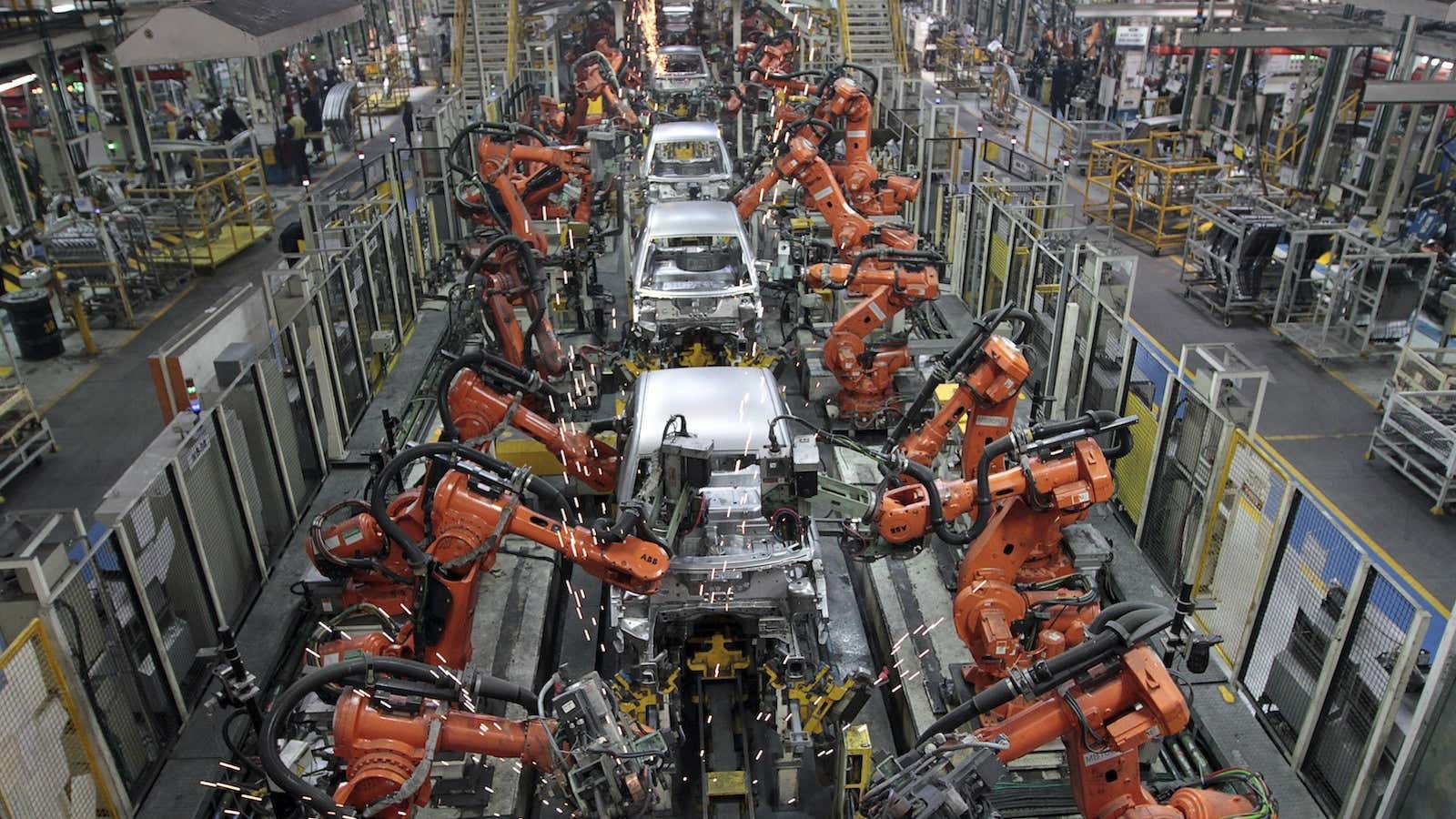

Kumar works in Manesar, India’s leading automobile hub, about 50 kilometers from Delhi, in Haryana’s Gurgaon district. Around 80,000 workers work here at more than 600 companies, with a majority producing components for cars and bikes.

Last week over morning tea, as night-shift workers emerged bleary-eyed, and day-shift workers trooped in with their tiffin-boxes, the young man in his twenties told me stories of the scores of accidents he had seen in the years since he arrived from his village in Bihar.

“In every factory, you would find at least ten boys with broken fingers,” he said. “About half of the boys who’ve come from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar to work in Haryana have lost their fingers.”

This sounded hyperbolic until I visited the hospital for workers run by the central government’s Employee’s State Insurance Corporation. Five patients sat in the orthopaedic department waiting for a doctor’s consultation. Four of them were cases of “crush injuries”.

“We see about 20 cases of crush injuries everyday,” said Dr Pankaj Bansal, the orthopaedic surgeon at the hospital. “In most cases, the fingers are auto-amputated, which means they have been lost even before the worker has come to us. In some cases, the entire hand is lost.”

Not just the orthopaedic department, even the emergency ward in the hospital sees a steady stream of crush injuries, which are also called cut injuries. The records examined by Scroll showed 20 cases in the ten days between November 19-28.

In the most immediate sense, the injuries are caused by a tall machine called the power press, which cuts, shapes or moulds metal by ramming it with a heavy piston-like arm. The worker operating the machine places the metal piece on the work table, presses a pedal or lever that brings down the arm. Once the arm pulls back, he removes the reshaped piece from the table, before repeating the process.

When the arm comes down before the worker’s hand is out of the way, it leads to amputations.

Shop floor supervisors and company managers blame such accidents on the lack of alertness on part of the workers. But accounts of injured workers reveal that the accidents are taking place in such large numbers because companies are saving costs at the expense of workers safety.

Nov. 18, 11 p.m. Vasudev had already clocked in 15 hours of work on the shop floor, shaping metal pieces that he was told would be fitted into the seat frames of Maruti cars. Starting 7 a.m., perched on a stool, the 22 year old had diligently worked his arms and legs at the power press machine in a rhythmic cycle—right hand to place the piece on the table, left leg to press the pedal, left hand to remove the piece. With a hourly production target at 240 pieces, he had to complete four work cycles in a minute, or one in 15 seconds.

“I thought it’s 11 p.m., let me hurry up, finish the work and get some rest,” Vasudev said. “I might have pressed the pedal too fast. Or the machine slipped…” Before he could remove the piece and his hand out from harm’s way, the machine’s arm came crashing down, crushing the top half of his right thumb.

But why was he working until so late? “The supervisor said a work order has to be completed. On such days, you can’t slip out even if you want to…”

Vasudev works at Sharda Motor Industries Limited. On its website, the company claims to be a leading supplier of front suspensions, seat frames and other components for Hyundai, Mahindra and Tata Motors. An email to the company’s management seeking a response on the accident went unanswered.

Not only are they hard-pressed to meet targets, workers say they are often not trained for the job. “Many of the workers who come to us are new to the industry and have not been trained to operate the machines,” said Dr Bansal.

Arvind Kumar is all of 19. He lost his left thumb this month while operating a power press at a company called Antech Engineers Private Limited, which makes clutches and stands for scooters and motorcycles.

According to him, the accident took place because of machine failure. “Something went wrong with this part, here,” he said, sketching the machine on my notebook. “It failed to stop the rotating wheel, and so the press came down even though I had not pressed the pedal.”

Machine failure usually occurs due to lack of maintenance and overuse. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration of the United States identifies problems with the electrical circuit of the machine’s clutch and brake control as a possible reason for lack of “control reliability”.

Scroll made attempts to call the management at Antech Engineers but could not get through.

Arvind Kumar joined the company at the start of November but was not given any training before he was made to operate the machine. “They said I didn’t need it because I had worked on the power press of another company for six months,” he said. “But the machine in the previous company was operated with a handle while the machine at Antech had a pedal.”

Given its magnitude, it is hard to believe that the epidemic of broken fingers could be stemmed easily, just if companies cared enough to install safety guards.

Two years ago, 30-year-old Rajkumar lost his middle and ring finger to a power press accident in RDC Steel and Allied Services Limited, a company that supplies auto-parts to Omax Auto Limited, which assembles them into larger parts for Maruti, Honda and other automobile companies. According to Rajkumar, at least another 20 workers lost their fingers and hands on the company’s shop floor in the last two years.

At RDC’s factory, the head of operations, Dinesh, admitted that 10-12 accidents have taken place, but added that they have stopped since the company installed safety guards and new machines six months ago.

Taking me around the shop floor, he showed me the newly installed pneumatic presses, which have inbuilt sensors that automatically stop the rotation of the machine’s arm if they detect any human presence in the working area. Although safer, the pneumatic presses are more expensive—each of the pneumatic machines cost the company Rs20 lakh ($32, 292) while the mechanical presses came for just Rs8 lakh ($12,917). “Eighty per cent of the presses in India are mechanical,” said Dinesh. The company has 12 pneumatic presses and 21 mechanical ones.

But even the mechanical presses could be made safer, he said, showing how the foot pedal in the machines had been replaced with a double hand safety mechanism. Only when the worker engaged both his hands in pressing buttons does the machine arm come down. The cost of installing the two buttons: just Rs28,000 ($450).

An even cheaper safety mechanism, Dinesh explained, was getting workers to use magnetic clamps, or rods with magnets installed at one end which could lift the metal pieces without putting the worker’s hands at risk. The cost of the clamps: just Rs25 ($0.40).

With such inexpensive safety devices available, why weren’t more companies using them, I asked Dinesh. “Because they slow down production,” he said.

Companies might be reluctant to install safety guards but Schedule VI of the Factories Act in India makes it legally binding for them to do so. “Our laws are good,” said Suresh Shrivastava, a former government employee who runs a firm called Safety Consultancy Services, “but we are bad at enforcing them.” Only five officers in Haryana’s labour department are empowered to carry out factory inspections in Manesar. One of them told me he manages to do just ten inspections in a month. Safety audits for the machines are often done by people appointed at the discretion of the labour department. “They often don’t have certification or even basic competence,” said Shrivastava.

A better way of eliminating amputations, he claimed, would be to make it mandatory for companies that make power presses to install safety guards in them. “They aren’t doing that at the moment,” he said. “It is like making bicycles without brakes.”

Shop floors could also be made safer if there was consumer pressure on the large automobile companies to compel their vendors to shape up. “Safety standards in Indian industry have improved in the last few years not because we care for our workers,” Shrivastava said, “but because our international buyers have put pressure on us.”

A spokesperson of Maruti Suzuki declined to comment on the injuries that have taken place in the factories of companies that are part of its supply chain. “We cannot comment as suppliers do not report injuries to us,” she said, adding that the company believed it was “a serious concern.”

“We organise safety audits for our primary vendors,” she said. “We are increasing the ambit of the safety trainings to include tier 2 and tier 3 vendors who are vendors to our primary suppliers…We are working towards it.”

This post first appeared on Scroll.in