Hong Kong

In China, they say that there are three genders: male, female, and female PhD. “It’s a joke that means we’re asexual and not feminine enough,” says Deng, a 27-year-old sociology PhD candidate from China’s southern province of Hunan, sitting at a small metal table outside the main library at Hong Kong University.

Deng, who asked only to be identified by her surname, is one of over 100,000 Chinese women who have been branded as the country’s next generation of spinsters. According to their many critics, they are aloof, unattractive, self-important careerists who, according to some Chinese academics and officials, threaten the country’s very social fabric by putting education before family.

Deng defies the stereotype. She is talkative, with a high, soft voice and a short bob that gives her a cherubic look. She is researching conditions at Chinese factories in the hopes of improving life for workers. One of her interviewees, a worker in the manufacturing hub of Guangzhou, was shocked to learn that she was working toward a PhD. “You’re not bad looking even though you’re a PhD,” Deng recalls him saying.

Today, more Chinese women are seeking advanced degrees than ever before. But as their numbers increase so do the criticism and ridicule leveled at them. It’s a worrying reflection, gender experts say, of increasingly conservative Chinese attitudes toward women even as the country’s citizens grow richer and more educated.

Stereotypes about female PhD students are part of broader worries in China over the number of women becoming shengnu, “leftover women”— those who have reached the ripe age of 27 without marrying. “Women are seen primarily as these reproductive entities, having babies for the good of the nation,” Leta Hong Fincher, author of the book Leftover Women: The Resurgence of Gender Inequality in China, told Quartz.

But the derision towards those with or earning PhDs, who typically don’t finish their degrees until the age of 28 or later, is particularly vitriolic. “There is a media-enforced stigma surrounding women with advanced degrees,” Fincher said, and much of this manifests online in social media.

In a recent discussion thread titled, “Are female PhDs really so bad to marry?” on a popular Chinese forum similar to the question-and-answer site Quora, one user posted (link in Chinese), “They are unscrupulous, hypocritical, filthy, and weak.” A user of the Chinese microblog Weibo wrote in September, “Female PhDs are the tragedy of China’s leftover women.” In an online poll on Weibo last January, 30% of over 7,000 voters said they would not marry a woman with a PhD (Chinese).

Aside from being called the “third gender,” female PhD students have also been nicknamed miejue shitai or “nun of no mercy” after a mannish Kung Fu-fighting nun in a popular Chinese martial arts series. They are sometimes referred to as ”UFOs,” an acronym for ”ugly, foolish and old.” At Sun Yat Sen University in Guangzhou, where Deng does some of her research, male students refer to the dormitory for female PhD students as the “Moon Palace,” the mythical home of a Chinese goddess living in painful solitude on the moon, with only a pet rabbit for company. “It’s like it’s a forbidden place where a lonely group of female PhD students live and no man wants to go,” Deng says.

“Ignorance is a woman’s virtue”

Educated Chinese women weren’t always treated this way. In the early days of the People’s Republic, the Communist party worked hard to overturn old Confucian ideas about women. Mao Zedong famously called on women to “hold up half the sky,” by going to school and taking up jobs.

As a result, high school enrollment for girls reached 40% in 1981 (pdf, p. 381), up from 25% in 1949, while university enrollment rose from 20% to 34% over the same period, according to a 1992 analysis by the East West Center in Hawaii. As many as 90% of women were working in the mid-1980s, according to the same paper.

Ever since China started dismantling its planned economy in the 1980s and 1990s, dissolving many of the state-owned enterprises that employed women, more conservative values have begun to resurface. Now traditional ideas about women are creeping back into Chinese society. “It’s like returning to the idea that ignorance is a woman’s virtue,” says He Yufei, 27, one of Deng’s classmates at Hong Kong University, quoting an old idiom used to encourage women to focus on their roles as mothers or wives.

Chief among these ideas is that no woman should occupy a position higher than that of her husband. According to Louise Edwards, a specialist in gender and culture at Australia’s University of New South Wales, a flood of soap operas, pop music, and movies from South Korea and Japan—historically patriarchal societies that never went through the kind of female liberation that China experienced—further reinforces this idea. “A PhD is the apex. It’s the top degree you can get, and by getting it you are thumbing your nose at the system,” Edwards said.

What is more, these traditional stereotypes happen to be convenient for the government at a time when China is facing a demographic problem. By 2020, Chinese men will outnumber women by at least 24 million, according to the National Bureau of Statistics. Some researchers argue that the concept of shengnu, ”leftover women,” was concocted by propaganda officials to pressure women into marrying as early as possible.

“The government is very concerned with all the excess men in the population who are not going to find brides. So it’s pushing educated women into getting married,” Fincher said. “The Chinese government doesn’t say anything about losing potential women from the workforce and that reflects their short-sighted concern with social stability.”

“They are already old, like yellowed pearls”

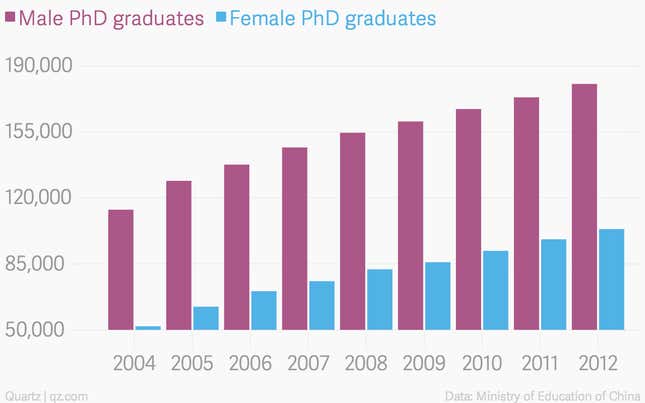

The PhD is a relatively new degree in China. Post-graduate programs were banned during the Chinese Cultural Revolution in the late 1960s. After that, the first PhDs weren’t awarded until 1982. Now, having expanded its higher education system in an attempt to become more globally competitive, China awards more doctorate degrees than any other country. It had 283,810 PhD graduates in 2012, compared to 50,977 in the US that year, according to government statistics.

Chinese women make up half of all undergraduate students and almost half of all master’s students, but they accounted for only 35% of the PhDs awarded in 2012, compared to 46% in the US. Young women outperform their male counterparts so much that some universities have started requiring higher test scores from female applicants.

“Although women are doing well in university, they usually stop at a master’s and there’s a reason for that. It’s partly because of this stereotype,” Edwards said.

It’s not just anonymous bloggers or male university students who deride women in higher education. In January, Chen Riyuan, an academic in Guangzhou and minor politician, said that single women who undertake doctoral degrees are like “products that depreciate in value.” The All-China Women’s Federation, a state-backed women’s group, infamously wrote on its website on International Women’s Day in 2011 that “by the time [women] get their MA or PhD, they are already old, like yellowed pearls.”

Some women, too, have internalized the belief that a PhD will torpedo their chances of settling down. “Many of my friends gave up their PhDs because they think they need to get a boyfriend,” said Meng Ni, a doctoral candidate at York University in the United Kingdom, who is studying the experiences of female PhD students in China.

The thankless road of learning

Women who decide to go for the top degree are choosing a hard path, either for their love of research or teaching, or in the hope of getting a decent job. “The job market is really competitive and many people think that with higher education, the more knowledge that they gain, they will be more competitive,” says Meng, the doctoral candidate at York University.

The hours are long and pay is typically meager—around 1,000 yuan (about $160) a month, plus a little extra for working as a teaching assistant or a residence hall monitor. Huang Yalan, a 25-year-old woman earning a PhD in communications at Tsinghua University in Beijing, lives in a small single dorm on campus and spends most of her day poring over articles on propaganda theory, her thesis topic. She sees her boyfriend only once a month. If she can find a job as a lecturer after she graduates she can expect a starting salary of between 3,000 and 6,000 yuan a month. It may be years, even decades, before she becomes a professor.

“I’ve never felt discriminated against for being a female PhD, but people are curious because they think a woman’s obligation is in the home or that studying and pursuing a higher academic degree is a man’s path,” Huang said.

For others, the prejudice has been more obvious. He, 27, says that she was turned down by a professor at a university in Beijing because he wanted to supervise only male students. And many Chinese academics aren’t interested in supervising female PhDs or hiring them once they graduate. Women held fewer than 25% of academic posts in the country in 2013, according to a Times Higher Education survey.

A 30-year-old graduate who asked only to be called Carrie, and who graduated with a PhD in communications this year from one of China’s top schools, Fudan University in Shanghai, said she was shocked when the first question a recruiter asked was whether she would have a child within a year. “I was so angry, but I had to control it. This is just how it is,” she said.

What’s bad for women PhDs is bad for China

Discouraging women from getting jobs or education hurts any country’s economy, and especially China’s. The country faces a rapidly aging population and a labor force that is expected to start shedding as many as 10 million workers this year. The working-age population, which has been shrinking since 2012, fell by almost 4 million last year. Two neighboring countries with similar demographic problems, Japan and South Korea, have both launched public campaigns to get more women in the workforce. China has initiated no such campaigns.

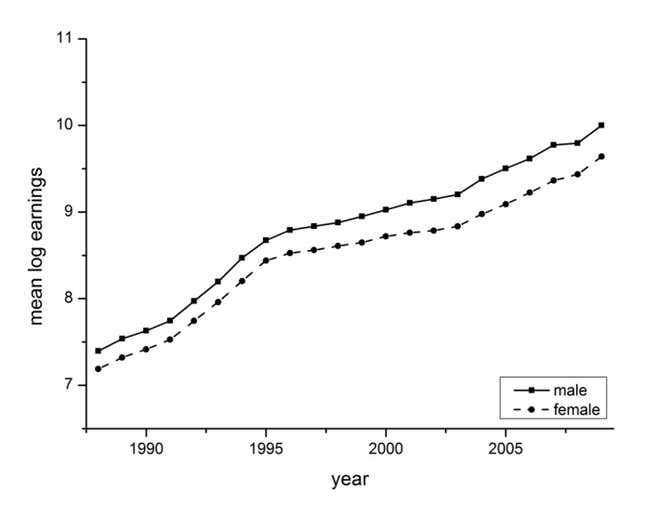

As a result, China’s female labor-force participation, once among the world’s highest, has been ticking downward. The proportion of urban women in the workforce fell to 60.8% in 2010, compared to 77.4% in 1990, as more women choose to stay home after having a child. On the World Economic Forum’s gender equality rankings, China now ranks 87th out of 142 (pdf) countries, just below El Salvador, Georgia, and Venezuela. The pay gap has also widened: One study found that between 1995 and 2007, women’s earnings, as a proportion of men’s, had fallen from 84% to 74%.

The fact that women are underrepresented in academia may also help explain why they are absent in policy-making circles and ultimately the government, where half of the members of the most powerful decision-making body, the Politburo Standing Committee (PSC) have PhDs. The percentage of women of ministerial rank or higher has remained below 10% since 1982 (p. 139). No woman has ever been nominated to the PSC or to lead the party.

But women PhDs are fighting back

For all the prejudices, women PhDs are quickly catching up with their male counterparts. From 2004 to 2012, the number of female PhD graduates increased 19-fold. In time, attitudes may change.

Of the dozen PhD students sitting in Deng’s shared office at Hong Kong University, a quiet fluorescent-lit room with thick blue carpet and beige plastic desks, more than half are Chinese women. A small Chinese flag, red with yellow stars, sticks out from one cubicle. Deng says she believes that she and her colleagues are good for China.

“I think female PhD students can show another kind of life for women,” she said. “As in, not living life through their husbands, sons, or brothers but showing women can be educated, independent, and happy.”