In the first few days of 2007, Steve Jobs introduced the world to the future of mobile: the smartphone. A computer and phone rolled into one, the iPhone came with revolutionary features for the time, including a 3.5-inch screen that reacted to touch, Wi-Fi connectivity, and a 2-megapixel camera. It cost $500 without a contract.

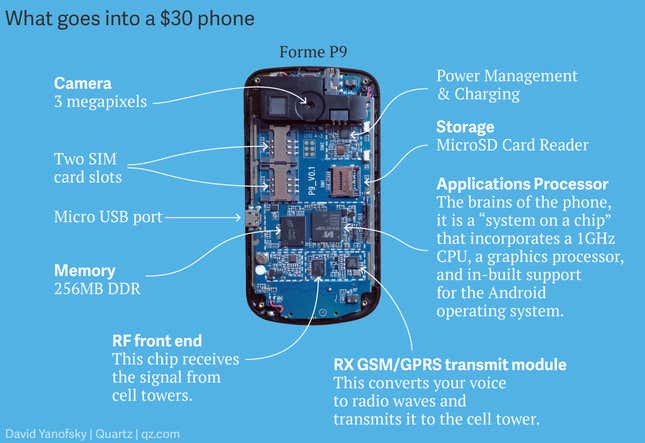

Last month, in India, I bought a Forme P9 smartphone. It has a 3.5 inch touchscreen, Wi-Fi connectivity, a 3-megapixel camera, and a host of features the original iPhone didn’t offer, including an extra SIM slot, FM radio, an app store, and expandable memory. It costs $32. In the three weeks since I bought it, the price has dropped another dollar.

In the next three years, between 500 million and 900 million people will start using the internet, reckons McKinsey. The vast majority of them will do it on cheap mobile phones not unlike the one I bought. This is the story of how we got here, what the internet looks like from a $30 phone, and what lies in the future.

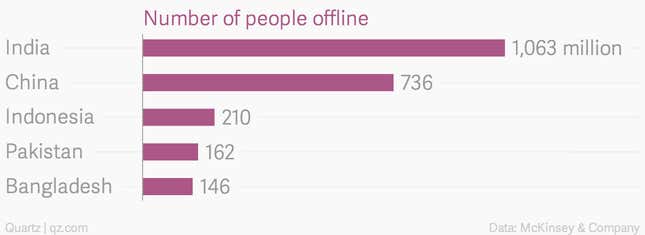

The phones are from India, which is the focus of this story simply because it is the single largest offline market in the world—and one that is expected to grow tremendously in the coming years. But the dynamics are similar across the poor world. “All the growth right now and for the mid-term is going to be at the low- and mid-end” says Andrew Dunn, an analyst at RBC Capital Markets, an investment bank. “And that’s come about particularly because of the rise of the middle class in China and India.”

The road to $30 phones

In exchange for Rs 1,989 ($32) on Flipkart, a big Indian e-commerce site, I received a smartphone that comes with WhatsApp, Facebook, and Google services pre-installed. The box included a USB cable and charger, a handsfree headset, a stick-on scratch-guard for the screen, and a one-year warranty (with a card listing 132 service centers across India). Someone, somewhere, presumably manages to eke out a living from these devices. The question is how.

There are three reasons smartphones tend to get cheaper over time, says James Gautrey, technology and telecoms analyst at Schroders, an asset management company. The first is Moore’s Law, a rule of thumb for the technology industry which, in a nutshell, states that computer processors double in power every 18 to 24 months. Looked at the other way, that also means the same processor should halve in price over the same period.

The second is general advancement in chip design. Features and functions that would once have required separate chips have over time been integrated into a single chip—a so-called “system on a chip.” This makes it possible to cram ever more technology into a tight space, such as a smartphone.

Third, newer handset makers in the developing world are happy to accept much lower margins than incumbents. “Where Samsung has traditionally taken 50%-60% margins, the new guys like Xiaomi will take 25% gross margin,” says Gautrey. All three trends are accentuated when innovation slows. When people can’t think of new things to add to a phone, they don’t need new chips. That means phones as a whole should get cheaper. It also means there is less to differentiate a high-end phone from a low-end one.

An additional reason for the sharp decline in prices has to do with efficiencies in the supply chain, which has helped lower the cost of handsets at the low-end and mid-end, says RBC’s Dunn.

The $30 (and above) phones themselves

I went to India with a budget of $200—the upfront cost for a new iPhone on a two-year contract in the United States—to see how many phones I could buy. Had I stuck to the low end and bought lots of identical $30 phones, I’d have come back with half a dozen phones and a few dollars left over. Instead, I bought a variety: a $30 Android device, a $30 Firefox OS phone, a $40 Android, and a $60 Android. This is how the $30-$60 Android devices of 2014 compare to the original iPhone:

I’ve been using each phone for brief periods back in London for the past three weeks, and every one, from the cheapest to the most expensive, is perfectly acceptable. Sure, the cameras are miserable, interaction with the device is a bit clunky, and except for the $62 Micromax, they all lack 3G data connectivity, meaning you’re effectively cut off from the internet unless you can find a Wi-Fi signal.

But any one of these phones is a giant leap from a “feature” phone, which is good for making calls, sending texts, playing “snake,” and that’s about it (regional services such as M-Pesa notwithstanding). On these phones, you can use Facebook—pre-installed on all of them—or WhatsApp. You can download games. You can email and surf the web. It’s a different world entirely.

For what it’s worth, my favorite of the lot is the Intex Cloud FX, a Firefox OS-based phone that looks good, works well and has the advantage of being web-based rather than native. That means even though it has a only few apps pre-installed, the phone can display many more “web apps” when connected to the internet. The battery life is terrible though. This is the only one of the four that fully discharges even when it’s been sitting around doing nothing.

The economics of $30 phones

Before a phone gets into the hands of an Indian customer, it is manufactured in China, shipped to India, distributed across the country, marketed, placed in stores and in e-commerce warehouses, and delivered to the consumer. At every stage, someone has to make some money off the thing. So how is it possible to sell a quasi-magical device that can make phone calls, connect to the internet, take photographs, and more, for $30?

“For the economics to work, you cannot go down to every phone and work out the profitability. You have to look at the business,” says Sanjay Kapoor, chairman at Micromax, India’s largest seller of smartphones ranging from $35 to $300 in retail. Being a large company with a line of higher-margin phones to absorb distribution and promotion costs certainly doesn’t hurt, but Micromax’s strategy is more nuanced than selling cheap phones at a loss in the hope that customers will stay with Micromax as they move up to more expensive handsets.

“India and markets like India are very value conscious. For any manufacturer to be profitable and sustainable, his understanding of consumer insights has to be very high so you don’t end up over-designing phones. You design the right phones for the right segments,” says Kapoor. That is the opposite of a Samsung-like strategy of chucking everything into a device. Instead, each device needs to do only what is required of it and nothing more.

An example of extreme segmentation comes from Forme, the Chinese company that makes the $30 Android device I bought. Its devices run in the $30 to $90 range and it is focused almost entirely on what Om Kumar, Forme’s marketing head in India, calls “tier 4 cities.” Even within this narrow range, segmentation is key. The phone I bought, Forme P9, comes without 3G. But there is a version of it, the Forme P9+, that has 3G and video recording. It costs $5 more.

The future of the $30 smartphone

The reason $30 is an important number is that it’s at the higher end for feature phones. Once prices for the two are comparable, smartphone adoption will accelerate. For the moment, devices at $30 are pretty bare bones, lacking even 3G (the means to carry data quickly), a prerequisite for a phone to be truly smart.

But the effects of selling cheap entry-level devices are already visible. According to Tony Navin, who runs electronics for Snapdeal, a large Indian e-commerce site, devices that cost less than $80 account for about a third of his total smartphone sales. Of those, two-thirds come from outside the dozen biggest cities in India and a majority of buyers are people upgrading from feature phones to smartphones.

Navin says a 3G-enabled smartphone for $30 is “the holy grail.” That is when internet penetration will take off. Such phones already exist in China, says James Bruce, who leads the mobile business for ARM, which designs nearly every processor that goes into every smartphone in the world. “You are seeing new features being delivered at these low price points.”

“If you compare a high-end smartphone from four or five years ago, the user experience a $50 phone delivers today would be comparable,” says Bruce. The same will happen five years into the future. In other words, today’s iPhone is tomorrow’s entry-level device.

This is good news for consumers but not necessarily for today’s leading handset makers, because their profit margins in emerging markets are razor-thin. ”That means you either have to come up with a brand new product for which you can continue charging a premium or you have to start competing on price, in which case margins are going to fall,” says James Gautrey of Schroders. “Or you have to exit completely.”