How to manage all your financial affairs from a $20 mobile phone

“I feel like a caveman who’s just been handed a Bic lighter,” reported Charles Graeber, a writer for Bloomberg Businessweek who recently went to Nairobi to check out M-Pesa, Kenya’s dominant mobile-money provider.

“I feel like a caveman who’s just been handed a Bic lighter,” reported Charles Graeber, a writer for Bloomberg Businessweek who recently went to Nairobi to check out M-Pesa, Kenya’s dominant mobile-money provider.

M-Pesa, which allows Kenyans to send each other money via a simple text message, is invariably cited when Western scribes wax enthusiastic about the miracle of mobile money in the developing world. And it may well seem miraculous to Americans, considering that when they want to send money to a friend, they still typically rely on hand-writing and then mailing a check (how quaint!)—whose recipient, if very technologically advanced, might use a smartphone app to take a photograph and upload it instead of going to the bank.

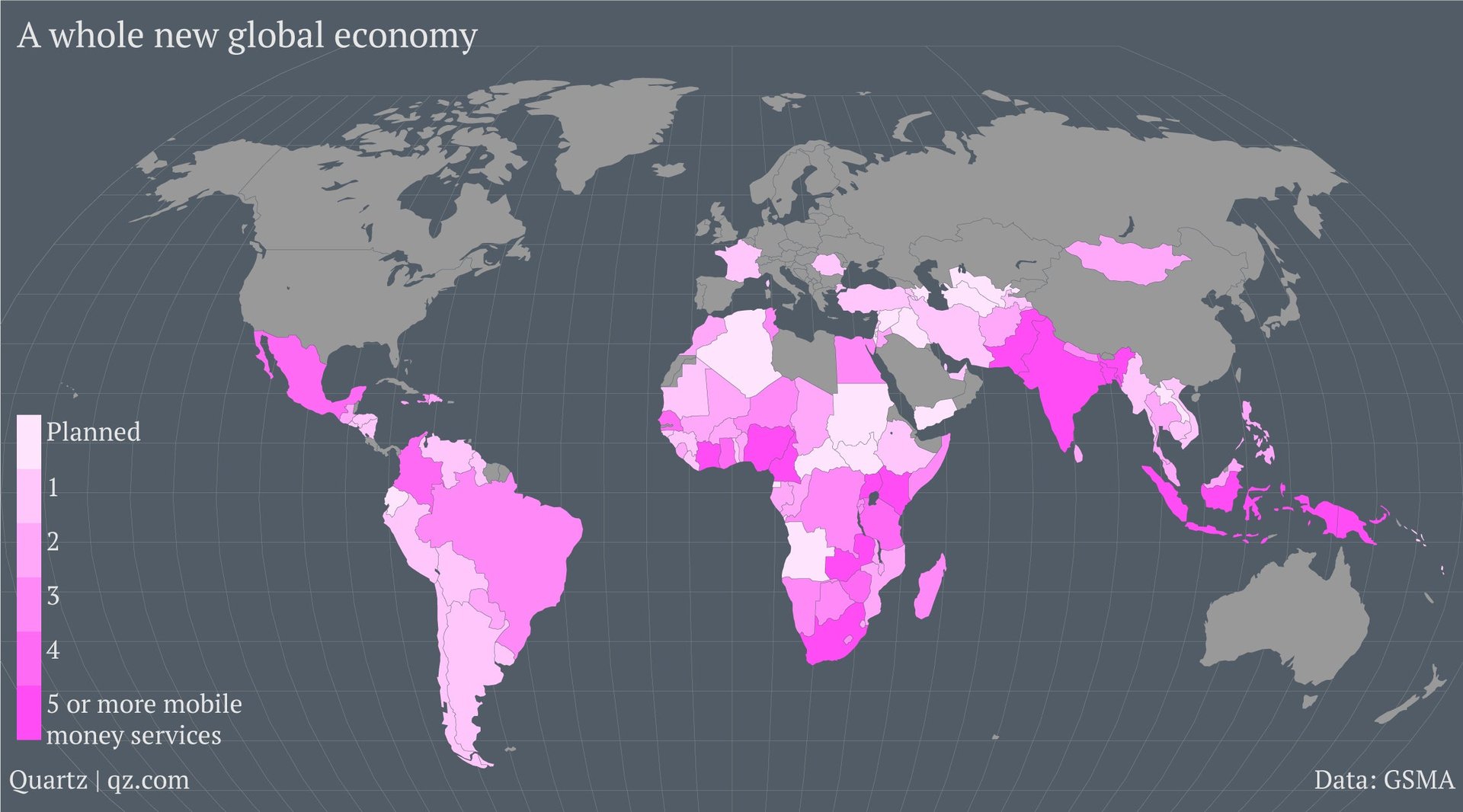

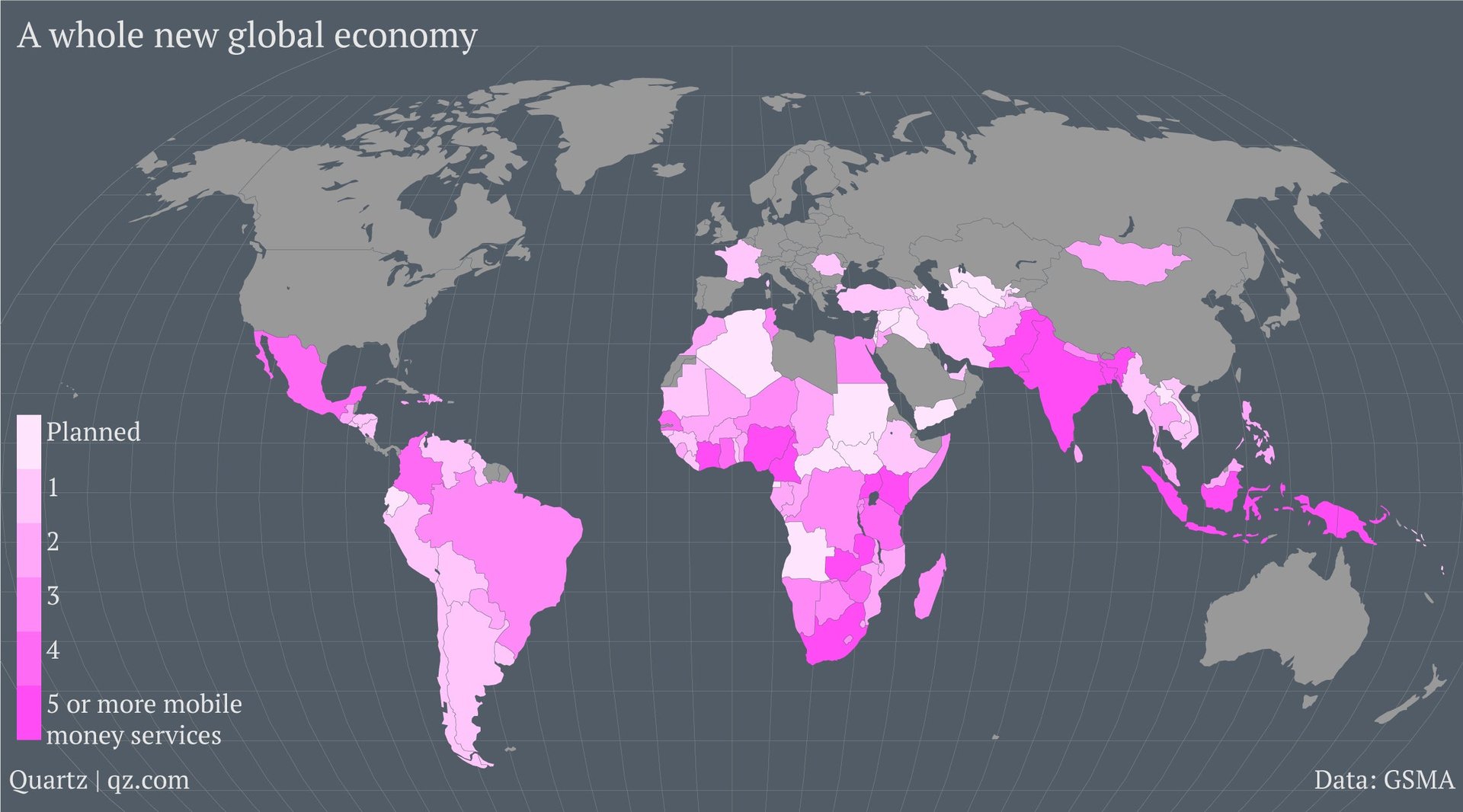

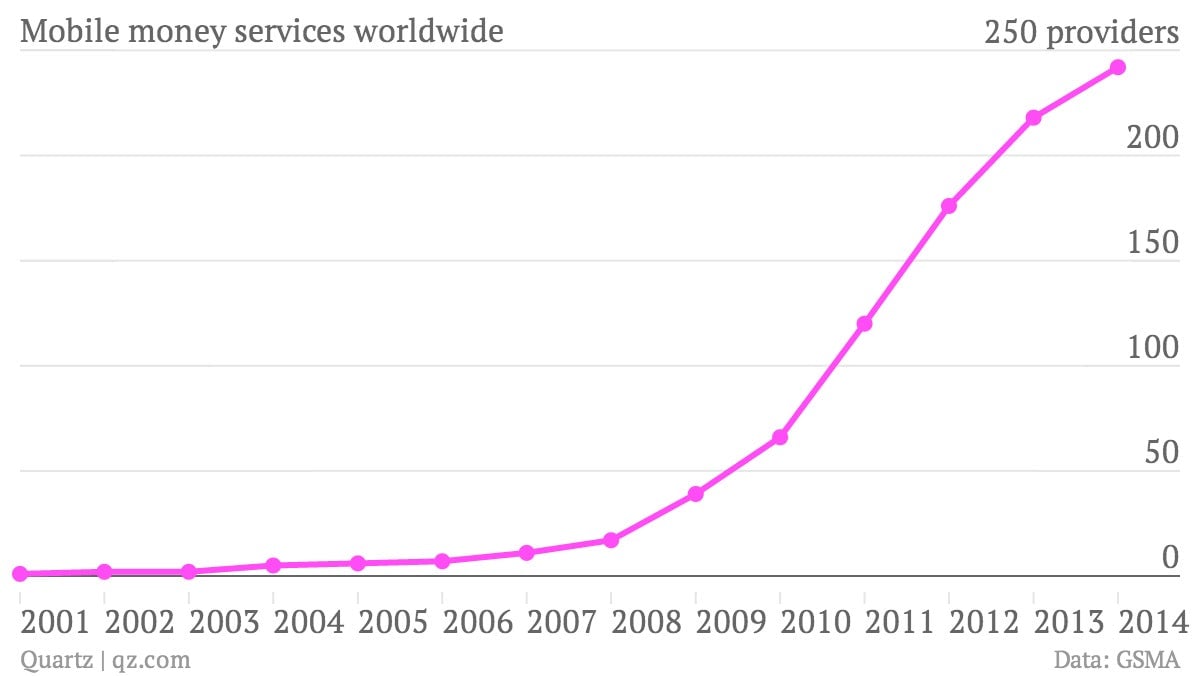

But Kenyans have already been using mobile money for seven years. And M-Pesa is now just one of 242 mobile-enabled e-money providers operating in 89 countries, boasting 203 million mobile money accounts between them, according to the GSM Association (GSMA), a trade association of mobile carriers. (Some 61 million accounts were active (pdf, p.19) in the 90 days to June 2013.)

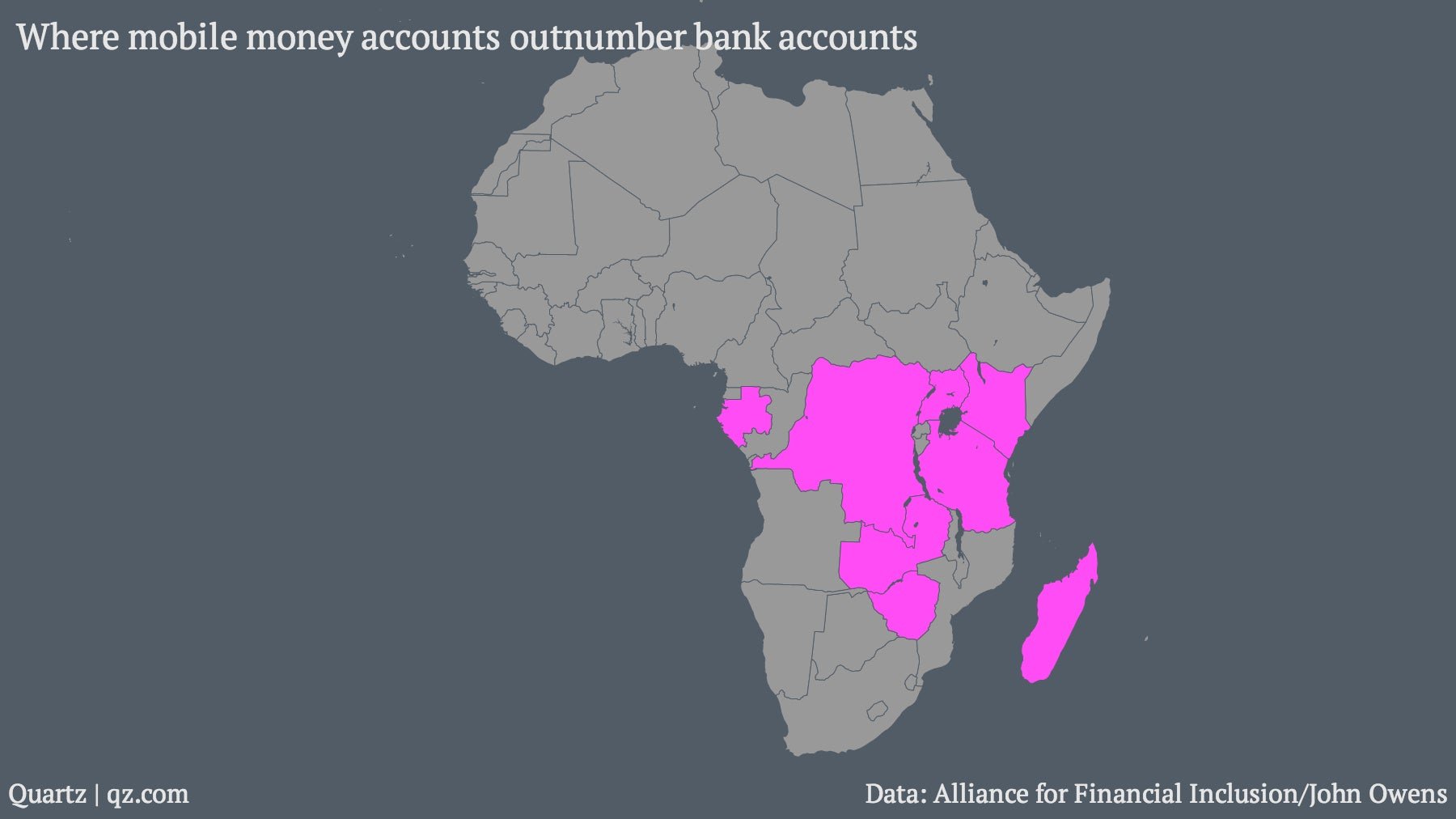

What’s more, in nine African countries—Cameroon, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Gabon, Kenya, Madagascar, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe—mobile-money accounts now outnumber bank accounts.

Mobile as a platform

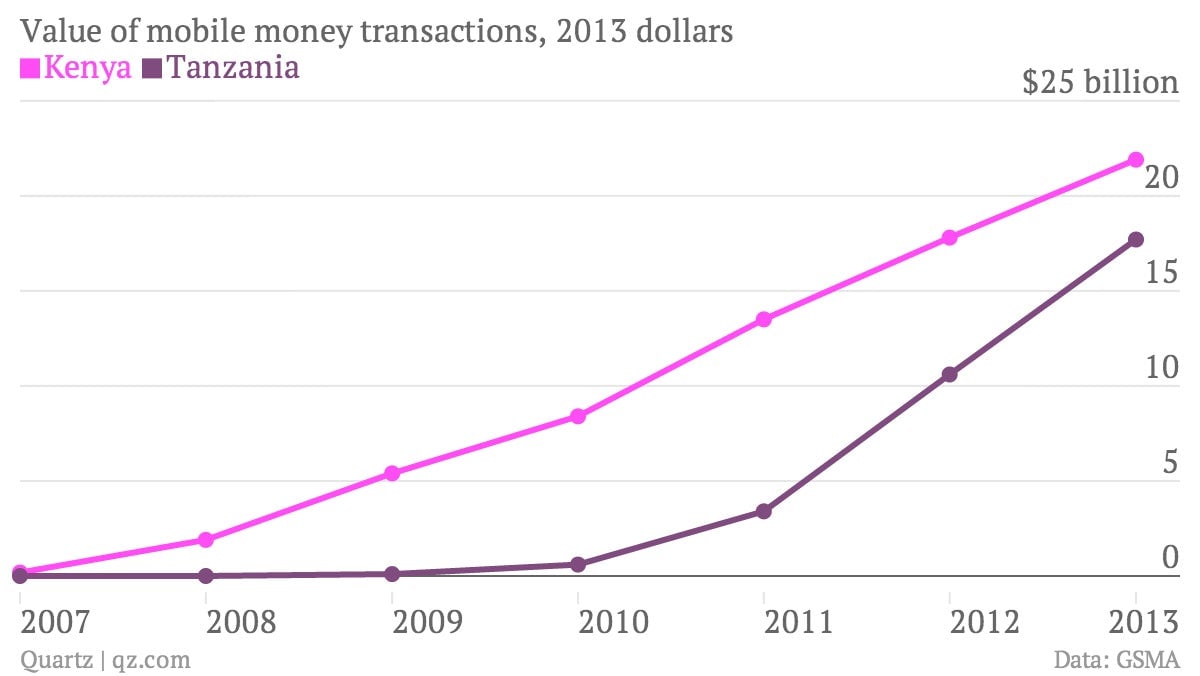

Kenya isn’t even the leader in mobile money any more. Had Graeber gone to neighboring Tanzania, he’d have discovered that 44% of adults there used some form of mobile money in 2013—ahead of Kenya’s 38%. Last December alone, Tanzanians conducted 99.9 million transactions (slide 7) worth a combined 3.1 trillion Tanzanian shillings ($1.8 billion). That’s all the more impressive considering only 14% of Tanzanian adults use banks, less than half the rate in Kenya, and on a par with Zambia towards the bottom of the table.

If that were where it stopped, Tanzania would just be a latter-day Kenya. But the country has also gone way beyond simple money transfer. The basic mobile phone is becoming the platform for a whole range of financial services in Tanzania—and increasingly other countries across the developing world.

How to spend it…

Where the West has the web, the poor world has Unstructured Supplementary Service Data (USSD)—a simple, text-based data-transfer protocol used on mobile networks. And it is being used for everything from day-to-day transactions to tax payments, and from insurance to savings.

Mobile money, like any other kind, isn’t much use if all you can do with it is send it to your friends. Businesses should be able to accept mobile money payments—all they would need is a mobile phone. But integrating mobile payments into business accounting can be a hassle. And several mobile money providers restrict the service to within their own networks, so you can’t pay someone who uses a different service.

Yet the deep penetration of mobile money in East Africa has attracted companies eager to make these problems go away. One such service is Kopo Kopo, which allows businesses to easily accept mobile payments and keep track of them online. It is increasingly popular in Tanzania and Kenya, the countries with the highest penetration of mobile money.

The government is noticing, too. Last year, the Tanzania Revenue Authority started allowing citizens to pay vehicle licensing fees through mobile money. According to the authority, this was a huge success, with collections jumping by 50% in the three weeks after the change. It also has the added benefit of fighting corruption, since it reduces contact with officials.

“You’re beginning to see that bringing down costs and improving efficiency is creating opportunities for people at all levels,” says John Owens, a mobile money policy expert at the Alliance for Financial Inclusion. Providers are also coming up with better software that allow businesses to pay their employees using mobile enabled e-money, he says. “And once you’ve got people receiving money, including their salaries, in their e-money accounts, it’s much easier for businesses to start accepting it and creating these opportunities and e-payment eco-systems.” The more money there is in the system, the more ways there will be to spend it.

…Or to save it

Mobile money wasn’t designed as a mechanism for saving. But the more things people can spend mobile money on, the more they’re likely to keep in their mobile wallets. At any given moment they’ll probably have some money sitting around unused, just like in a bank account. So Tanzanian regulators are in the process of allowing banks to pay interest to mobile operators, which will then distribute it to their users (pdf, author’s note).

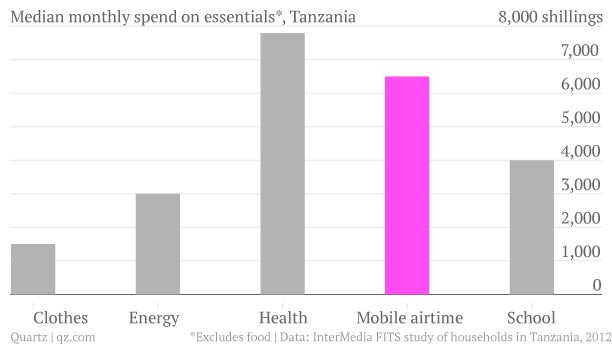

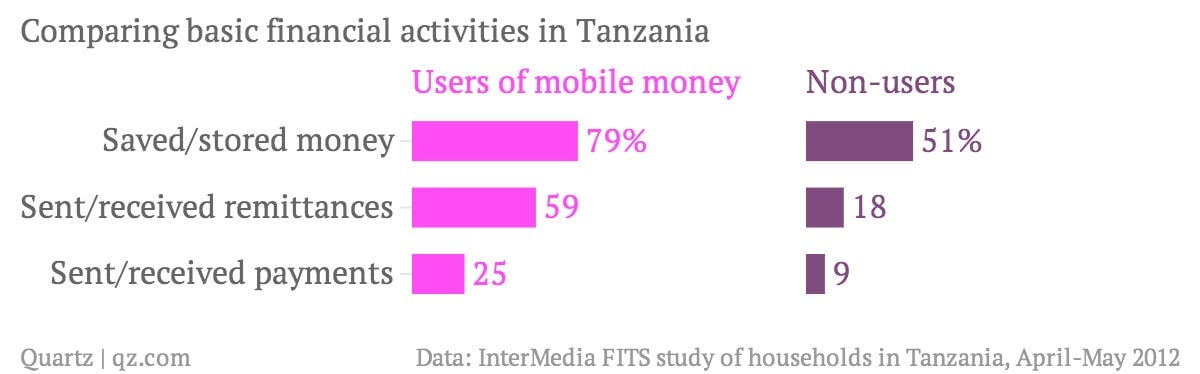

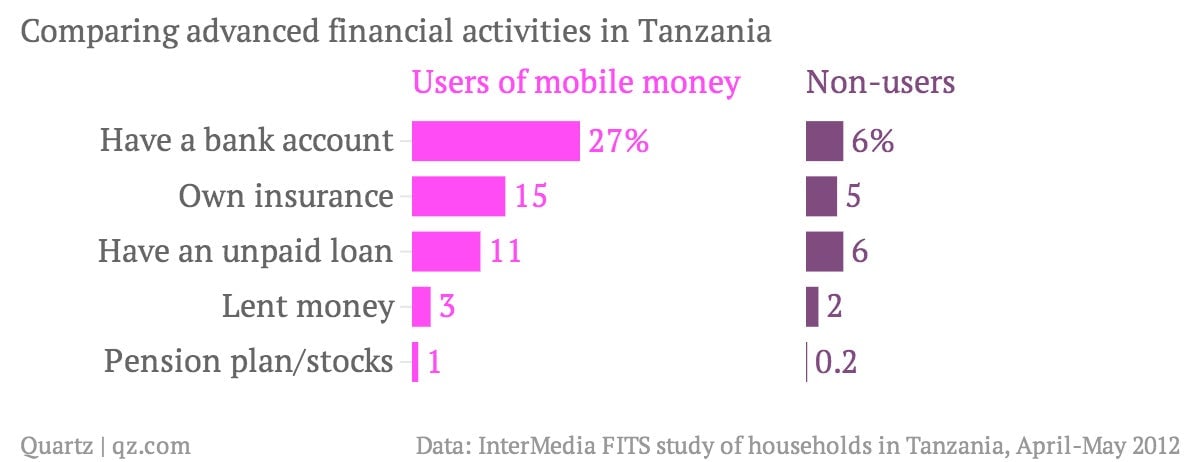

A few shillings extra probably won’t help anybody marry off their daughters or buy a new phone. But it does lay the foundations for more advanced financial services. “Some mobile savings customers choose to save even though they don’t earn interest, demonstrating there is customer demand for mobile savings either for securing against theft or saving for high-price purchases,” reports the GSMA (pdf, p.58). A survey by InterMedia, a development researcher, found that Tanzanians with mobile money accounts were likelier to use more advanced financial services like bank accounts, insurance or loans than those without.

In Kenya, the Commercial Bank of Africa teamed up with M-Pesa to allow users to move mobile money into bank accounts and apply for loans. Their credit rating is based on how much and how often they top up their prepaid connections (a useful proxy for credit-worthiness). The service, called M-Shwari, signed up a million customers in 41 days; it hit 3 million in five months (pdf, p.3). By February this year, more than 6 million Kenyans used the service, receiving 7.8 billion Kenyan shillings ($89 million) in loans. The service has a default rate of only 3% of the money lent out.

Get it covered

Bima is a microinsurance firm operating in Tanzania and other countries. Insurance is a hard sell to poor farmers who haven’t used financial services, says Andrew Kuper of Leapfrog, an investor in Bima: It takes a lot to convince the farmer to spend money on something whose value depends on everything else going wrong. And if there are no calamities, the farmer is likely to think the insurance, whether for his life or his crops, was a waste of money.

Bima’s solution is ingenious. Instead of trying to sell insurance directly to consumers, it sells it to mobile operators, who hand out insurance policies to their subscribers for free. The operators’ incentive is that in these countries, where fixed-term mobile contracts are rare and subscribers jump promiscuously from one provider to another depending on the rates and time of day, a free extra service like insurance is a way to keep customers loyal.

What’s more, having got subscribers hooked on free insurance, mobile operators can then entice them to pay a little extra for an upgrade—the same “freemium” model beloved of smartphone app makers and game developers. In Ghana, for instance, one mobile carrier offered to double the insurance coverage for a monthly fee of one Ghanaian cedi ($0.33).

According to Tigo, a mobile carrier, “Bima has registered more than 500,000 customers after just two years of operations” in Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania’s biggest city. Four out of five of its customers earn less than $2.50 a day. The same operator covered 1 million Ghanaians within one year of launching the service. In Namibia, an operator called Leo (now TN Mobile) reached 15% of the adult population. Robi in Bangladesh has some 4 million clients, while Telenor in Pakistan signed up 400,000 people in four months, according to the Access to Insurance Initiative.

How to send it

Despite advances in mobile phones and mobile money, there remains one big obstacle: Few mobile operators can transfer money to other operators. This means a national or international financial system based on mobile payments can’t develop.

In a way, this is how the mobile web now works in the West. Apple’s app store is separate from Google Play, which is separate from Amazon’s Kindle store, and just because you own something on one device doesn’t mean you can use it on another. By June last year, just 0.4% of all transactions went to another mobile network, according to the GSMA.

Yet here too, Africa is leading the way. This month, three Tanzanian mobile operators agreed to allow mobile money transfers between networks. According to a press release, this is the first such agreement in Africa. It will go live by the end of June.

Indeed, collaboration is booming. In February, Tigo started cross-border remittances between Tanzania and Rwanda. In April, the Central Bank of West African States helped Bharti Airtel and MTN Group develop a cross-border mobile transfer system between Ivory Coast and Burkina Faso, a first for West Africa. (Malaysia and the Philippines have allowed cross-border remittances since 2007.)

At the end of April, nine mobile operators with 582 mobile connections across 48 countries in Africa and the Middle East committed to make their mobile money offerings work across their networks. With interoperability comes greater cohesion and opportunity for new services. If it’s done right, it could form the foundation of a whole new global financial-services industry. And the US and Europe will be far behind.